This round-up is part of Harvard Magazine’s series “At Home with Harvard,” a guide to what to read, watch, listen to, and do while social distancing. Read the prior pieces, featuring stories about the history of women at Harvard, the climate crisis, Harvard in TV and in the movies, and more, here.

The magazine’s “Vita” department introduces historic figures whose lives should be better known, or offers new views of already well-known figures. Many, but not all, have been affiliated with Harvard. Over the years we’ve covered authors, artists, actors, astronomers, historians, craftspeople, scientists, politicians, military leaders, and more. Below are some of our favorites.

Novelist Ann Petry, in an undated photograph by Edna Guy

Though Ann Petry’s The Street became the first novel by a black American woman to sell more than a million copies, Petry did her best to keep to herself. “Continuous public exposure, though it may make you a ‘personality,’ can diminish you as a person,” she told a radio interviewer in 1996, 50 years after the novel’s publication. Petry’s insistence on “self-ownership” is fascinating, and Farah Jasmine Griffin ’85, BF ’97, does a great job of illuminating the life of a preeminent author whose work largely speaks for itself.

At a gathering, circa 1920, of members of the Liberty League, Trotter sits in the first row (fifth from right).

hotograph courtesy of Columbia University Library

William Monroe Trotter, A.B. 1895, was never happy with the status quo. Using the Boston Guardian, a newspaper he founded in 1901, he challenged the anti-black violence and denial of civil rights that remained constant after Reconstruction. “Only the colored people themselves can determine their political, social, and economic future,” he said. He took this responsibility seriously, confronting white progressives who believed racial discrimination was solely a Southern problem. A fascinating piece on a remarkable man.

-Jacob Sweet, Staff Writer/Editor

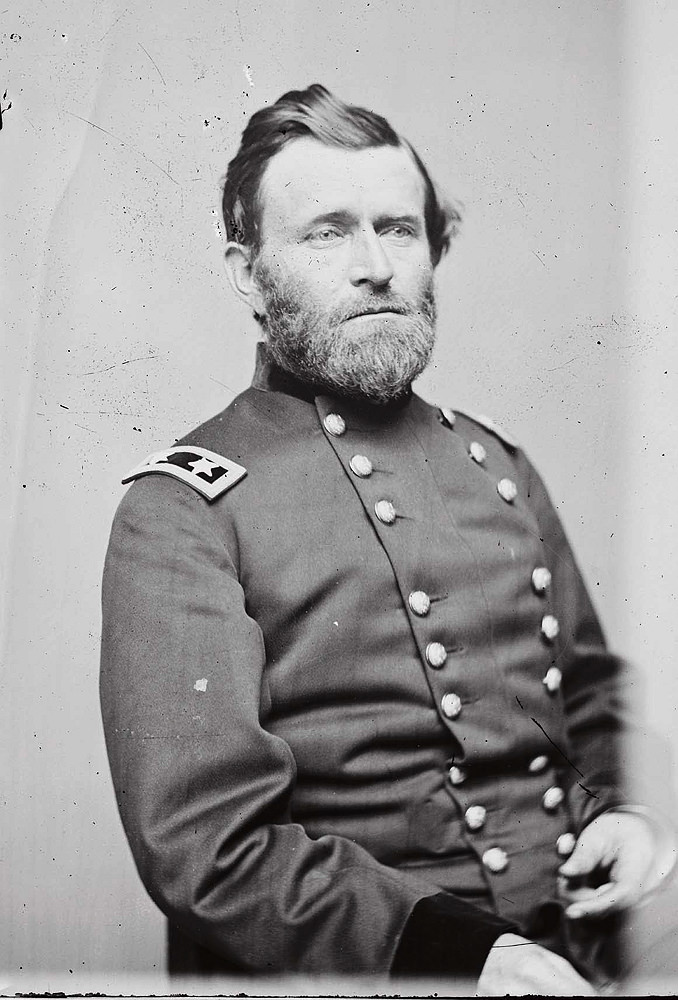

A formal wartime portrait

Photograph from the Mathew Brady Collection/Library of Congress

“Terse, cool, free of melodrama,” is how Elizabeth Samet ’91 describes the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant—and she describes the man as much the same. A professor of English at West Point and author of the beautiful and powerful A Soldier’s Heart, Samet edited a recent annotated edition of Grant’s memoirs, and her portrait here of the aging general grapples with our own American moment: the revisionist Civil War narrative and glorification of the South’s Lost Cause that still infects the nation’s politics.

Darden preparing river-cane splints for weaving, c. 1900.

Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 2004.24.26766B.

“In American history,” writes Harvard cultural historian Ivan Gaskell, “no class of person remains more obscure than indigenous women.” And in this profile, he brings out of obscurity one such woman: Clara Darden, a virtuoso weaver of river-cane basketry, who lived her whole life on a Chitimacha reservation in southern Louisiana and whose masterpieces now hang in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography. Born in 1829 or 1830, Darden was the sole surviving practitioner of her particular art, which dated back millennia. She led a remarkable life, but it was not until after her death that she and her artwork received full recognition.

~Lydialyle Gibson, Associate Editor

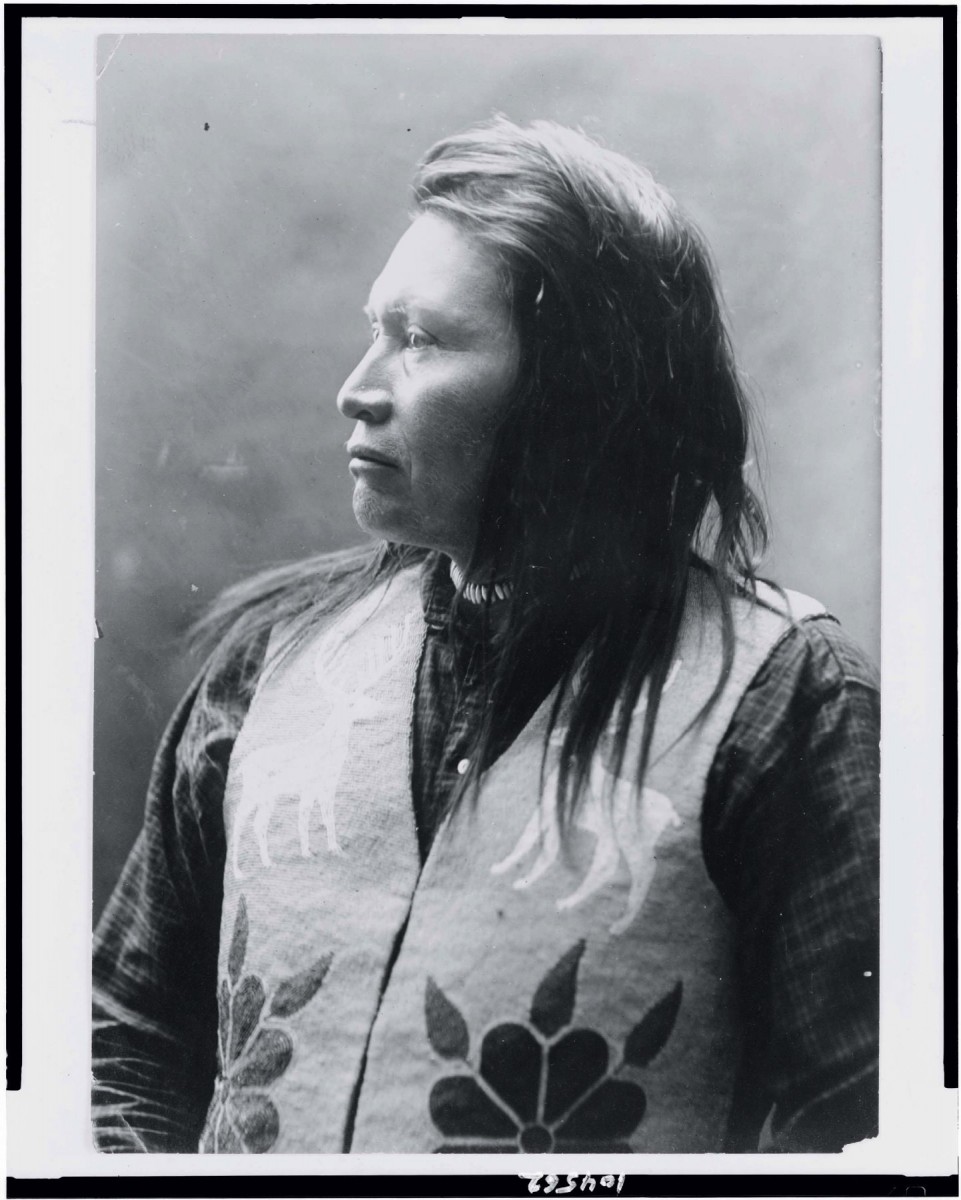

A portrait of Yellow Wolf circa 1909

Photograph from The Library of Congress

Not until he was 52 did the Nez Perce warrior Yellow Wolf begin to tell his story. When he finally did, speaking through an interpreter, he discovered that his words had power. As Daniel J. Sharfstein ’94 relates, Yellow Wolf’s story “gave the lie to official accounts” of the 1877 Nez Perce War, when 750 Nez Perce men, women, and children “outran and outfought the army across some 1,400 miles through the northern Rockies and the buffalo plains, only to be captured a day or two shy of the Canadian border.” Official accounts had “greatly exaggerated the number of Nez Perce warriors, covered up a vicious massacre of their women and children along the Big Hole River in Montana,” and incorrectly characterized Chief Joseph, one of the tribe’s leaders, as “a battlefield genius.” The full import of the story was far greater, writes Sharfstein, because it led to the creation of one of the most important archives documenting the Native American experience, and in the process, catalyzed the transformation of Washington State University into a modern research institution.

Forensic pioneer Joseph T. Walker (at left) collects blood and scraps of flesh from the bathtub drain of a 1936 murder victim.

Photograph by Leslie Jones/Courtesy of the Boston Public Library

Forensic science today is a robust discipline—and a staple of television crime shows. But the application of scientific principles to investigation, and the use of the results in court, is relatively new. Chemist Joseph T. Walker, Ph.D. ’33, played an outsize role advancing the field when he created the first statewide scientific crime lab in 1934, in Massachusetts, and then taught toxicology in Harvard’s department of legal medicine from 1939 on. He pioneered methods for determining shooting distances, detecting writing on burned paper, and analyzing barbiturates in the blood, and helped solve high-profile cases that drew international attention to forensics. When he died, “an honor guard of police troopers from all six New England states and New York” attended his funeral.

~Jonathan Shaw, Managing Editor

Courtesy of Tom Reiss

Whenever I see the name “Alexandre Dumas,” I think about a beloved television show from my childhood, Wishbone, in which a Jack Russell terrier named Wishbone dresses up as literary characters and becomes a player in classic stories. This is how I learned about The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. But this article isn’t about Alexandre Dumas the famous author—it’s about his father, also named Alexandre Dumas, a famous half-black, half-French army officer. Napoleon became jealous of General Dumas and did everything he could to strip his name from history. Thankfully, author Alexandre immortalized his father’s life in his novels that became classics around the world.

Frances Perkins

The women featured in Vita have been equally impressive. There are two in particular I’d like to point you toward: Frances Perkins, the social-justice advocate and secretary of labor under Franklin D. Roosevelt, who championed the New Deal; and Murasaki Shikibu, the Japanese court lady who wrote what is often considered the first novel, the extraordinary Tale of Genji, a thousand years ago.

~Kristina DeMichele, Digital Content Strategist

Harvard affiliates often display prowess in fields not necessarily associated with ivy-covered liberal-arts colleges. One of them, who died much too young, was the legendary fly-fisherman Ken Miyata, Ph.D. ’80, of whom a friend recalled: “Ken waded in and started casting, and within 10 minutes most of the other fishermen had gotten out of the river and were sitting on the banks, watching him.” That is praise of the highest order.

~Jean Martin, Senior Editor

More from “At Home with Harvard”

- Spring Blooms: Your guide to accessing the Arnold Arboretum as the seasons turn in Boston

- Harvard in the Movies: Our favorite stories about Harvardians on screen

- The Literary Life: Our best stories about the practice and study of literature

- Night at the Museum: Our coverage of Harvard’s rich museums and collections

- Nature Walks: Walking, running, and biking in Greater Boston’s green spaces, even while social distancing

- Supporting Local Businesses: Our extensive coverage of local restaurants and retailers, and how you can support them during this time of crisis

- Medical Breakthroughs: Our best stories going deep into the ideas and personalities that will shape the medical care of tomorrow

- Rewriting History: From race and colonization to genetics and paleohistory, our favorite stories about the people reshaping the study of history

- The Climate Crisis: Highlights from our wide-ranging coverage of the environment

- Crimson Sports Illustrated: With 2020 winter sports ending early and the spring collegiate season wiped out almost entirely, we look back at Crimson highlights from past years.

- The Real History of Women at Harvard: Stories covering the admission of women, the Harvard-Radcliffe merger, the rise of women in the faculty ranks, Harvard’s first woman president, and more

- The Undergraduate: Our favorite student essays on the undergraduate experience

- The Secret Lives of Animals: From zoology and evolutionary science to animal-rights law to the joys of local wildlife, a selection of our favorite animal stories

- Harvard on the Small Screen: Our coverage of the creators, writers, and actors in your favorite TV shows