This round-up is part of Harvard Magazine’s series “At Home with Harvard,” a guide to what to read, watch, listen to, and do while social distancing. Read the previous selections, featuring articles about the climate crisis, racial justice, Pride month, and more, here.

it has become widely accepted that wealth inequality in the United States has reached crisis levels. And during the current coronavirus recession, when more than 40 million Americans have lost their jobs, that gap threatens to become decidedly worse. Many economists, legal scholars, sociologists, and others at Harvard have focused their efforts on inequality for more than a decade. Some of that work is now coordinated in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences’ Inequality in America Initiative. Below, we’ve compiled some of Harvard Magazine’s extensive coverage of inequality over the years, covering virtually every dimension one might think of—including the vast wealth gaps on Harvard’s own campus.

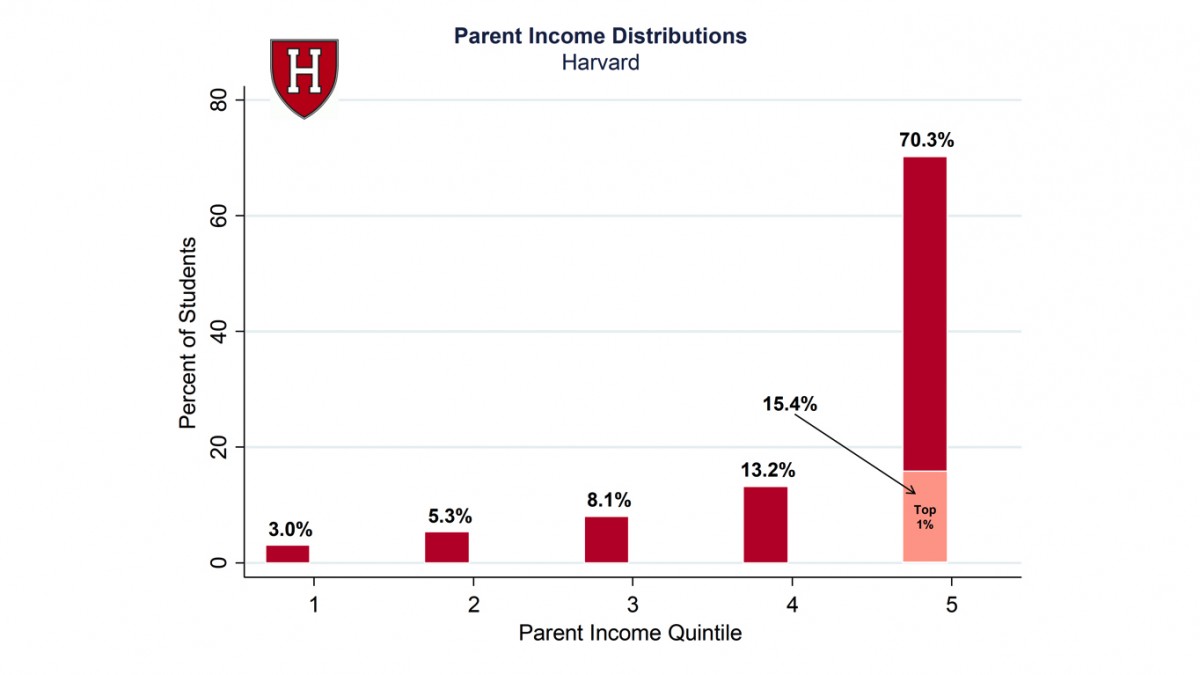

Harvard students’ family incomes by national income quintile, for students born between 1980 and 1991

Courtesy of the Equality of Opportunity Project

The first line of my colleague Marina Bolotnikova’s 2017 news story on Harvard’s economic diversity problem states that the College “has almost as many students from the nation’s top 0.1 percent highest-income families as from the bottom 20 percent.” Those numbers emerged from a massive nationwide study of 30 million college students, conducted by a group of scholars that included Harvard economist Raj Chetty. Additionally, the study revealed that more than half of Harvard students come from the top 10 percent of the income distribution, and more than two-thirds from families in the top 20 percent. Worryingly, the authors found, “At top colleges overall, the proportion of students from the richest 1 percent of families has increased during the last decade, while the proportion from the bottom 40 percent has decreased—a significant finding that had previously been obscured by the increased number of students at Ivy League schools receiving Pell Grants.” Also important: the study suggests that “elite universities are major engines of economic mobility, and they could do more if they enrolled more low-income students.”

Findings like these are an important part of the background context for other Harvard Magazine stories published in recent years: in 2008, Elizabeth Gudrais looked at the drastically rising numbers of Harvard graduates who go on to work in the finance industry—drawn, in large part, by its extremely high salaries. Explicating research on this topic by Harvard economics professors Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, Gudrais described a massive shift during the past 40 years—at Harvard, and across the country—as college graduates who might once have gone into law or medicine or other fields now tend toward investment banking, finance, and consulting. (Of late, high-paying technology jobs have also attracted many graduates.) “More remarkable than the growth of finance, Katz and Goldin say, is the fact that Harvard graduates, with all the options open to them, still decide to pursue careers in the arts, the nonprofit sector, and academia.”

And in a 2006 personal essay, “The (Other) Crew Captain,” then-junior John A. La Rue, a Ledecky Undergraduate Fellow at the magazine (who would go on to a career in speechwriting), described what life was like as a member of Dorm Crew, cleaning classmates’ bathrooms as part of his financial-aid obligations. He recalled uncomfortable encounters with parents and students, surprising discoveries about self and society, and the double-edged nature both of being ignored and being seen. And, unavoidably: the enormous affluence of many of his classmates. “Crossing through common rooms and bedrooms filled with obvious wealth—plasma-screen TVs three feet wide, brand-new leather couches, designer clothes strewn around—it’s hard to ignore the gulf between my own experience and the apparent lifestyles of a considerable number of my fellow undergraduates,” La Rue wrote. Later, he observed, “The gap between what I know and what they take for granted catches me by surprise, and their frame of mind entirely astonishes me.” The whole essay is sharp and affecting, well worth reading and reflecting on.

~Lydialyle Gibson, Associate Editor

Claudine Gay, then-social science dean and Cowett professor of government and of African and African American studies (and now dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences), launched the inequality initiative.

Photograph by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

“Unequal America,” a prescient (2008), feature-length examination of increasingly evident income inequality, begins vividly, on a point that resonates sharply amid COVID-19: “When Majid Ezzati thinks about declining life expectancy, he says, ‘I think of an epidemic like HIV, or I think of the collapse of a social system, like in the former Soviet Union.’ But such a decline is happening right now in some parts of the United States.…Poor health is not distributed evenly across the population, but concentrated among the disadvantaged.” The disturbing health outcomes documented then have shown up in even more disturbing detail during the pandemic. Harvard scholars are analyzing the problem, but it is deep-seated.

Perhaps no act is more devastating to a family than eviction: loss of shelter and often goods; frequently, displacement of children from their local school; social stigma; and other disruptions and humiliations that those who have never experienced the situation can barely imagine. Sociologist Matthew Desmond, then a member of the faculty, published pioneering work on the phenomenon based on his on-the-ground research in Milwaukee. “The fundamental issue is this: the high cost of housing is consigning the urban poor to financial ruin,” he found. And as we have learned, “eviction is a cause, not just a condition, of poverty.” Contributing editor Elizabeth Gudrais, a former Harvard Magazine staff member, reported “Disrupted Lives” from Wisconsin.

Anthony Abraham Jack

Photograph by Jill Anderson

Anthony Abraham Jack, assistant professor of education, has detailed the vast cultural and economic gulf that separates first-generation and low-income students from their high-income peers at elite colleges—increasingly so at places like Harvard, as the College has made a determined effort to recruit and admit more first-gen/low-income students. This spring, as campus was emptied to protect community members from the coronavirus, some students had no safe home to return to, or, in some cases, no practicable way to study online from home—a vivid illustration of the income gap in society, now manifest here. Jack’s research on The Privileged Poor (those high academic achievers admitted to elite schools, but coming without substantial financial support at home, and often from under-resourced high schools) applies with special force now. For some underprivileged students, he says, their campus experiences are their first direct encounter with economically comfortable fellow citizens—and vice versa. It takes care to make that experience productive, and not devastating. For more on the socioeconomic differences in society and on campus, read “Harvard’s Class Gap” by Richard Kahlenberg ’85, J.D. ’89.

~John S. Rosenberg, Editor

Benjamin Sachs and Sharon Block

Two recent episodes of Harvard Magazine’s podcast, Ask a Harvard Professor, look at inequality from two different and crucially important vantages. In “When Did Labor Law Stop Working?” Harvard Law School’s (HLS) Benjamin Sachs and Sharon Block argue that U.S. labor law needs to be fundamentally rewritten to give power back to ordinary workers. Read more about their vision in “Reworking the Workplace,” our print coverage of HLS’s new project, Clean Slate for Worker Power. In “Can the U.S. Healthcare System Be Fixed?” healthcare economist David Cutler talks about just that—and about how the extremely high cost of medical care in the United States makes the system especially bad for people without the means to pay. Be sure to read as well Cutler’s superb, thoroughly engaging recent feature for our magazine, “The World’s Costliest Health Care.” He writes: “Speaking morally, as well as economically, is the biggest challenge in health policy.”

Corporate power is a principal driver of America’s extreme degree of inequality. If terms like “industry consolidation” put you to sleep, try reading my short 2019 article “The New Monopoly,” about why the domination of much of our economy by a few mega-corporations is a huge problem for both workers and consumers (who are, after all, in many cases the same people).

~Marina Bolotnikova, Associate Editor

“By pursuing prudent policies to protect and advance their own institutions—awarding no-need scholarships, giving admissions preferences to children of alumni, offering applicants the option of early decision, and so on—these leaders have, collectively, added to both the economic forces that have intensified the academic disparities between colleges and the advantages enjoyed by affluent applicants.”

In this 2017 feature story, Charles Clotfelter, Ph.D. ’74, reveals the great economic chasm between private universities, public universities, and historically black universities. This article is a must-read to understand how inequalities widened, and what we need to keep in mind to achieve any semblance of equality in the future.

~Kristina DeMichele, Digital Content Strategist

Sendhil Mullainathan

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Could poverty be a self-reinforcing cognitive trap? Works of fiction in literature (The Prince and the Pauper) and film (Trading Places) have explored variants of this theme extensively: what would happen if a poor man suddenly was given all the social and financial advantages of a rich man, and the rich man was stripped of his connections and wealth, left to fend for himself on the street? “The Science of Scarcity,” Cara Feinberg’s deft profile of Sendhil Mullainathan’s empirical research on the subject, is a welcome scientific look at what happens when people are faced with scarcity, whether of food, money, or companionship. The feeling of scarcity—just thinking about it—impairs reasoning ability, reducing a superior intellect to merely average, or an average intellect to “borderline deficient.” As Mullainathan (now at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business) and his research partners explained, describing the results of one of their experiments, “Simply raising monetary concerns for the poor erodes cognitive performance even more than being seriously sleep deprived.” The research points to the need for improved policies that take scarcity deficits into account.

Before she entered politics, Elizabeth Warren was Gottlieb professor of law and a fierce advocate for the working and middle classes. In “The Middle Class on the Precipice,” an article Harvard Magazine published in 2006, she debunked the idea that the problems facing the middle class have been driven primarily by excess consumption—unnecessary spending. Armed with data, she showed that it has been basic needs that swallow an increasing share of middle-class families’ incomes: the costs of housing, health insurance, education, transportation, childcare, and taxes. And even though family income has increased (in large part due to the entrance of increasing numbers of women into the workforce), which has offset rising costs, that shift also creates greater overall risk: if either worker in a two-earner household is let go, families that are already barely paying the bills face the possibility of financial ruin.

~Jonathan Shaw, Managing Editor

More from “At Home with Harvard”

- Spring Blooms: Your guide to accessing the Arnold Arboretum as the seasons turn in Boston

- Harvard in the Movies: Our favorite stories about Harvardians on screen

- The Literary Life: Our best stories about the practice and study of literature

- Night at the Museum: Our coverage of Harvard’s rich museums and collections

- Nature Walks: Walking, running, and biking in Greater Boston’s green spaces, even while social distancing

- Supporting Local Businesses: Our extensive coverage of local restaurants and retailers, and how you can support them during this time of crisis

- Medical Breakthroughs: Our best stories going deep into the ideas and personalities that will shape the medical care of tomorrow

- Rewriting History: From race and colonization to genetics and paleohistory, our favorite stories about the people reshaping the study of history

- The Climate Crisis: Highlights from our wide-ranging coverage of the environment

- Crimson Sports Illustrated: With 2020 winter sports ending early and the spring collegiate season wiped out almost entirely, we look back at Crimson highlights from past years.

- The Real History of Women at Harvard: Stories covering the admission of women, the Harvard-Radcliffe merger, the rise of women in the faculty ranks, Harvard’s first woman president, and more

- The Undergraduate: Our favorite student essays on the undergraduate experience

- The Secret Lives of Animals: From zoology and evolutionary science to animal-rights law to the joys of local wildlife, a selection of our favorite animal stories

- Harvard on the Small Screen: Our coverage of the creators, writers, and actors in your favorite TV shows

- Extraordinary Lives: From our “Vita” section, extraordinary profiles of authors, artists, activists, and more

- Great Legal Minds: Our favorite stories on the minds reshaping American law

- Harvard History through a New Lens: Some of our most notable stories about obscure, dark, or surprising episodes in Harvard’s history

- Health and Fitness: Our extensive coverage of Harvard’s breakthough health and wellness research

- Pride Month: Stories of Harvard's LGBTQ life, research and history