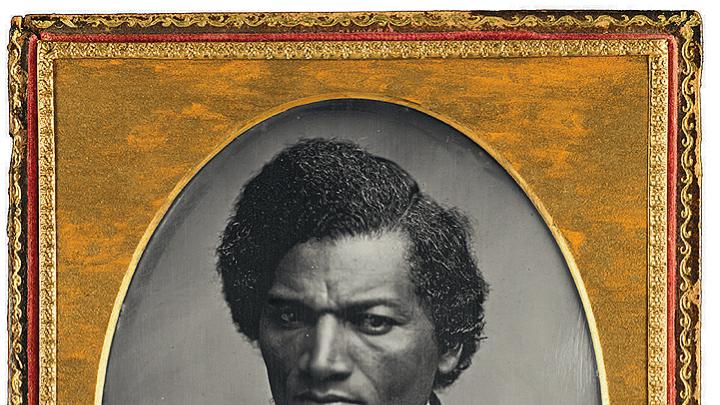

Eight months into the Civil War, in December 1861, Frederick Douglass delivered an address at Boston’s Tremont Temple about photography. The new medium, he argued, had the potential to transform how Americans saw one another by challenging racist stereotypes. “Poets, prophets, and reformers are all picture-makers—and this is the secret of their power and of their achievements,” Douglass said in the speech. “They see what ought to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.”

Some in the crowd were puzzled by Douglass’s choice of subject: photography seemed a trivial concern amid the fight for abolition. For more than 150 years, scholars, too, largely overlooked the address in their analyses of his politics. But in recent years, the speech, entitled “Pictures and Progress,” has become foundational to a growing body of scholarship about the intersection of politics and aesthetics—including by Sarah Lewis, Loeb associate professor of the humanities and associate professor of African and African American studies.

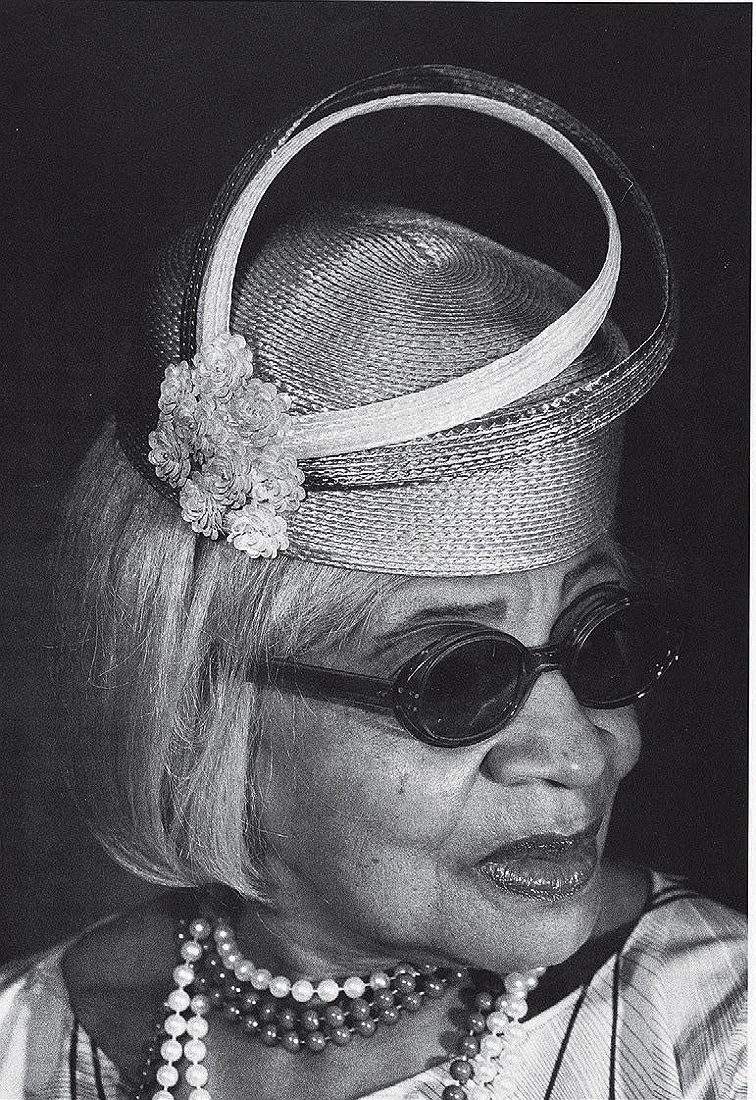

Harlem 2000, by Coreen Simpson | Photograph courtesy of Coreen Simpson

Douglass’s focus on the power of images—even during a time of political upheaval—wasn’t a coincidence, Lewis argues. Instead, it was a recognition of the fact that “racial domination and ideology were secured not only by norms and laws…but also by narratives,” she writes in The Unseen Truth, forthcoming from Harvard University Press this fall. Those narratives drew upon images that entrenched the myth of white supremacy—images circulating in textbooks, newspapers, and other media that had become ingrained in Americans’ imaginations.

If racial ideology was secured by more than norms and laws, then it would take more than norms and laws to uproot it. Douglass, who sat for more than 160 portraits, was the most photographed man in America during the nineteenth century. He understood that “[j]ust as images had served to reify racial boundaries, they could also undo them,” Lewis writes. With each photograph he sat for, he contributed to this undoing, his likeness challenging popular racist depictions of African Americans.

Since 2016, Lewis has taught about the connection between visual representation and American citizenship in a course, “Vision and Justice: The Art of Race and American Citizenship.” She also extends her work beyond Harvard through Vision & Justice, a civic initiative that seeks to “reveal the foundational role visual culture plays in generating equity and justice in America.” As part of this enterprise, one of her projects included guest-editing a 2016 special issue of Aperture Magazine that examined the “role of photography in the African American experience.” Lewis curated images by photographers such as Carrie Mae Weems, Deana Lawson, and Lorna Simpson, placing them alongside commentary by writers including Fletcher University Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr.

For the cover of the Aperture issue, Lewis selected a portrait taken by the photographer Richard Avedon of Martin Luther King Jr. with his father and son. “King seems to hover, his gaze directly at the camera and almost through the camera, straight to us,” Lewis says of the image in an interview. “That penetrating gaze of all three,” she continues, “transforms the image from a family portrait into an image of the collective human family, and effectively invites us into that family.” In this portrait, seeing is not unidirectional but a mutual act: King’s gaze into the camera makes viewers feel that “we must always see ourselves in his sight.” With that sense of being seen comes responsibility, Lewis says, and the image helps us “better understand the work we must do to enlarge our portrait of the human family.”

Beyond her work on individual images, Lewis also studies the act of vision itself. “Seeing is not just a retinal act. It’s never been about observation only,” she says. “Seeing is about reading the world. We perceive the world through these narrative layers of received histories we have about the people around us.” Douglass spoke about this idea in “Pictures and Progress” when he referred to “thought pictures”—collective images people carry in their minds that can either reinforce or challenge stereotypes.

The history Lewis studies has culminated in what she calls a “crisis of regard” in the United States—with debates over monuments and bans on “critical race theory” that she considers part of a long legacy of “unseeing” history. In this context, it’s important to Lewis that she makes her work public. Beginning in October, Aperture will publish a series of Vision & Justice monographs dedicated to lesser-known black photographers, such as Coreen Simpson. Lewis also plans to begin hosting public sessions of her Vision and Justice course, including at the Aspen Ideas Festival.

Through this work, she hopes to disseminate the images she studies and to transform the way people see one another—as Avedon achieved in his portrait of the three Kings. “The heart of the collective human project is finding ways to see ‘the other’ as you,” Lewis says. “It is not the work of the humanities alone, but a critical civic tactic for how we recreate the society in which we are honored to live.”