Commencements, the sages say, are beginnings. About to receive diplomas certifying that the world is now their oyster, the joyful graduates-to-be agree, mostly. But they also lament the endings: the loss of liberty that comes with student life, the scattering of fast friends to distant removes (i.e., Wall Street, Silicon Valley). On this latter point, for Harvard’s 367th Commencement, the youngsters appeared wise, for several important endings were at hand: the presidency of Drew Faust and deanships of Radcliffe’s Lizabeth Cohen and the education school’s James E. Ryan (respectively, returning to the faculty and assuming the University of Virginia presidency) on June 30, and of Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) dean Michael D. Smith as soon thereafter as a successor is tapped. Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) dean Xiao-li Meng, on sabbatical this year, is also concluding his service.

Already missing was University marshal Jackie O’Neill, whose beaming smile animated 14 iterations of the Morning Exercises, and made more palatable the authority she exercised to keep the whole shebang on schedule; she retired last December (making timely way for a successor to organize the installation of president-elect Lawrence S. Bacow this coming October 5). Interim marshal Margot Gill, plenty busy welcoming the hundreds of international visitors Harvard greets each year, didn’t need to herd the late-May throngs as well. So University provost Alan Garber ran this morning’s show, expanding his customary narration of the conferring of degrees; and Faust introduced the student speakers for their three customary “parts.” (O’Neill was, appropriately, a guest at the Wednesday evening dinner for honorary-degree recipients.)

The weather gods probably don’t much care who is show-runner. With a considerate nod to Faust (a celebrated historian), they consulted the records for the past 11 years (a record 92 degrees on the Wednesday of Commencement week 2010; the muddy ruins of Harvard Yard after the 375th-anniversary party in 2011; the chill soaking last May—and, oh, yes, the rain at her installation ceremony)—and then delivered a stunner this morning: 56 degrees at 7:00 a.m., with a robin's-egg-blue sky thoughtfully decorated with a puff or two of cloud, comfortably dry (and a forecast high of 69 degrees). Goldilocks surely would have approved. At the same early hour, as the happy crowds flowed through the security gates, a pair of bagpipers tootled their limbering-up exercises outside the former Inn at Harvard, now the home-in-exile for many denizens of Lowell while their House is being renovated. The day even sounded perfect.

On the Way to the Day

Winter yielded to spring grudgingly this year, with occasional spikes of heat that signaled summer to come. It was sufficiently temperate and wet to reward Cambridge with terrific lilacs by May 10, following a socko showing from the cherry trees and redbuds. The grounds crew had good growing weather for restoring the Old Yard’s particularly hard-hit former lawns in late April and early May, and got at the earthen-scented work of mulching the dickens out of everything in the first dozen days of May. Tercentenary Theater was being wired and otherwise prepared for the Big Show by that weekend, and the platform tent was en route: plenty of assembly required—and effected on Monday, May 14. The banners were hung and the ginormous video screens installed May 17, preceding the delivery of chairs and tables (and the impending premature death of those hopeful young blades of grass).

Commencement connoisseurs could detect a subtle but important tweak in the schematics: the band and choir—previously parked on risers and a platform over the wheelchair accessible entrance to University Hall—have won new pride of place: this year they sang and tooted their stuff from a covered plot up front, toward Thayer Hall (to the left of the tent as seen from the audience: facing Memorial Church and the main platform for honorands and University personnel). The musicians could credit the recent renovation of the church, which resulted, in part, in the murder of some shrubbery formerly on the site.

Monday, May 21, was flawless. Residual lilacs were still in full perfume at Dana-Palmer House. Eager College graduates-to-be were already posing in their caps and gowns on the Widener steps, indulging adoring family members and friends without so much as a whisper of complaint (so far). Drew Faust, who had more than her fill of graduation rain in Cambridge last May, popped over to Boston College, where she was awarded an honorary degree under what The Boston Globe accurately reported was “a cloudless sky at BC's Alumni Stadium.” It would not have been purple prose to say the blue overhead was impeccable. At 2:00 p.m., the temperature was 70 degrees, the air dry and fresh; it seemed a shame that Faust (who will not be attending her fiftieth at Bryn Mawr) had to meet with the Harvard fiftieth reunioners and their significant others indoors, at Sanders Theatre, at 4:30.

By 5:00, the student speakers and their coach, Richard. J. Tarrant (see biographies and texts below), were on the Commencement platform, beginning a rehearsal in situ—trying to imagine, or put out of mind, what those 32,000 chairs would look like with humans seated in them.

Tuesday dawned overcast, a bit muggy, with a slightly cooler forecast—a mercy for the Phi Beta Kappans, who would have to get capped and gowned to proceed into Sanders Theatre for the Literary Exercises at 11:00 a.m., and their undergraduate peers in general, scheduled to waltz into Memorial Church three hours later for their baccalaureate talking-to by President Faust. Showers moistened the morning a bit, and it remained gray and damp: only fair, given the prior day’s weather, the need for the resplendent greenery to get something out of the week, and a welcome prospect that enduring rain now would promise a clement day for Commencement proper.

A beautiful day began early on Wednesday, May 23, as a powerful sun dispatched most of the lingering clouds before 8:00 a.m.—an hour during the semester when students are already hard at work missing their first classes. The morning light intensified the azaleas, dogwoods, and horse chestnuts, all in peak bloom, and brightened the spring-green leaves everywhere. The sun did its thing, delivering afternoon highs in the 80s, as the Commencement machine warmed up for a full slate of the ROTC commissioning ceremony, class days, and countless reunion symposia—and promised clear conditions, agreeably cooled by ocean breezes, for the morrow.

The Week That Was

The Commencement odyssey begins with the Phi Beta Kappa Literary Exercises in Sanders Theatre, this year featuring a pair of alumni: poet Kevin Young ’92, director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library and poetry editor at The New Yorker, and orator Neil Shubin, Ph.D. ’87, a paleontologist who is Bensley professor of organismal biology and anatomy at the University of Chicago.

Kevin Young

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Young read from his new book of verse, Brown. His selections included two poems about childhood experiences—his playing baseball in Kansas, and his son going on a sleepover—and a sonnet sequence about his own College days (“We were black then, not yet/African American, so we danced/every chance we could get”). Shubin, drawing on his graduate studies, explained how, as a scientist, he learned to see the evidence around him in new ways—much as had, say, Charles Darwin. He then connected the work of science to contemporary concerns, observing that “We live in an age where people talk of alternative facts, fake news, and junk science. Those adjectives—‘alternative,’ ‘fake,’ and ‘junk’—make it ever more important that we gain the ability to take a cold look at marshaling and evaluating evidence in making decisions. And doing that means confronting our own very human limitations.” Perhaps even more tellingly, he told the stellar young scholars, “One lesson of science, for me, happens to be the least discussed—humility. Humility in the face of the unknown, and more importantly, in the face of our blindness.” Only with humility could people learn to see.

In her last Baccalaureate address, Faust drew upon College dean Rakesh Khurana’s theme about the transformative effects of a Harvard education to talk about the texture and meaning of those transformations—for the students, and for her younger self. Transformation, she said, “is different from change. It has a direction. It creates a new form out of a familiar thing. It’s thorough, it’s often radical, and, when it’s about us, usually positive.” Transformation is not merely personal, she said; rather, it is about becoming a transformative agent, a role that she explained had been assumed by the guest speaker on Thursday, U.S. Representative John Lewis, LL.D. ’12, the civil-rights leader. She underlined the principles of a liberal-arts education as a foundation for transformative work, since it “prepares you to…see the world in order to understand how we can transform it.” She continued:

Think of the habits of mind that underpin every field of knowledge: the imperative to seek out diverse points of view when we lack perspective; the patience to deliberate in disorienting strangeness; the capacity to improvise in the face of the unexpected—including when to listen, and when to do nothing. From literature and the arts we gain imagination and empathy, a second sight on our common humanity. From history [Faust’s own discipline], we draw courage against all hope, understanding that things were once different, and can be different again. From science we learn humility and persistence, knowing that a sudden insight can re-frame the universe.

Finally, she said, “transforming the world is a long haul,” referring to the life and death of Martin Luther King Jr. (see below about 1968 and the assassination of King after the graduating class had chosen him to be its speaker).

Along the way, she, like Shubin, expressed concerns about the current moment. During their undergraduate sojourn, Faust told the students, they had “observed the fraying cords of civility and trust. By the end of 2016, as juniors, you found yourselves at the heart of an institution whose motto is ‘veritas’ in a climate where ‘alternative facts’ fuel public discourse, and ‘post-truth’ was the Oxford English Dictionary word of the year.”

At the ROTC commissioning ceremony, Wednesday morning, the six students present to take their oaths (a seventh was commissioned earlier so she could compete in the women’s national sailing championships this week) were addressed by both Faust and Belfer professor of technology and global affairs Ash Carter—the U.S. Secretary of Defense from 2015 to 2017. Advocating the role of both diplomacy and military force where required, he told the newly commissioned second lieutenants and ensigns, “One last thing: the profession of arms is a profession based on honor and trust.”

Photograph by Jim Harrison

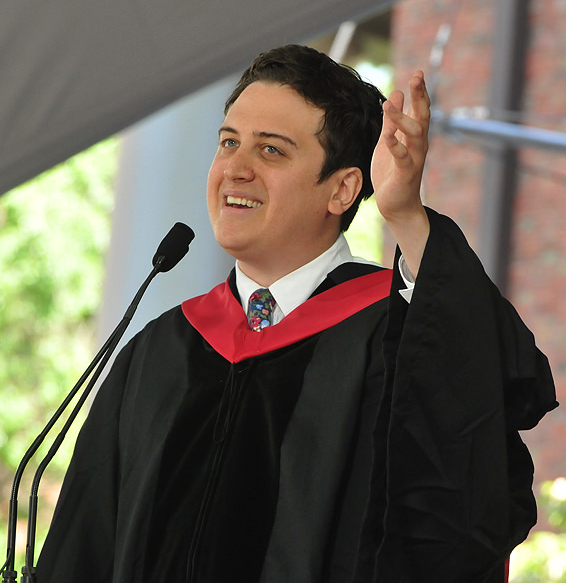

Saying that the “education business is the freedom business,” Harvard Graduate School of Education convocation speaker John Silvanus Wilson Jr., M.T.S. ’81, Ed.M. ’82, Ed.D. ’85, drew on his training in education and religion, and his life experience as a higher-education leader, to deliver a rousing speech-cum-sermon. Noting the temper of the times, he told the degree candidates, “you should feel lucky to be entering the world at such a powerful freedom moment” when “the quest for freedom swirls like the spirit…” and has “caused people to march.” Pertinently, “Teachers are marching…holding strikes and walkouts for…the freedom to teach without being undermined by basic deficiencies,” he said. Students, beginning with those from Parkland, Florida, are marching because “they want freedom from violence and the threat of violence….They simply want the freedom to be safe to learn.” Women are marching for “their optimal empowerment and to finally and completely upend a toxic culture that has existed for far too long. They want freedom from the tyranny of silence and the crime of zero accountability around sexual violence, harassment and misogyny,” said Wilson. “Black folk are still marching…of late, just to insist that black lives matter. They are seeking freedom from the scourge of racial bias in criminal justice and throughout American life.” Beyond his immediate audience, he might have been setting the stage for Representative Lewis’s address on Thursday afternoon.

There was conventional graduation oratory, to be sure. The Harvard Kennedy School candidates heard from John Kasich, the Republican governor of Ohio. Presidential campaign battles behind him (and perhaps before him, too), he chose to speak about faith. “The winds and change and fads and culture knock me off my bearings,” he said. “I need to have a compass.” That compass, he revealed, is faith. “Christians and Jews and Muslims all basically have the same view of human life. Human life is special. Human life is above all other life. The Creator created this human life above all else. It is our duty to reflect the character of our Creator and to recognize that every human being is made in the image of our Creator.” Drawing on a favorite text, he told the students, about to enter the public sphere,

There’s a guy in the Old Testament by the name of Daniel. They put him in the lion’s den. And guess what? We all enter the lion’s den. It’s just a matter of how we handle it when we’re there. There’s a price to pay for standing up, but when you do stand up, you go down in the minds of people around you as a hero, as an inspiration.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the College’s Class Day speaker, melded the classical kind of oratory for the occasion with a slight contemporary overlay, thus:

If I were asked the title of my address to you today, I would say, “Above all else, do not lie.” Or “don’t lie too often”—which is really to say, “Tell the truth.” But lying, the word, the idea, the act, has such political potency in America today, that it somehow feels more apt….Today, the political discourse in America includes questions that are straight from the land of the absurd. Questions such as, “Should we call a lie a lie? When is a lie a lie?”

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Photograph by Jim Harrison

“The biggest regrets of my life are those times when I did not have the courage to tell the truth,” she continued. “There is nothing more beautiful than to wake up every day holding in your hand the full measure of your integrity.”

The tone turned overtly political at Harvard Law School, where U.S. Senator Jeff Flake, Republican from Arizona, railed alternately against President Donald Trump and his administration, the “America First crowd,” and fellow members of Congress for lying “utterly supine in the face of the moral vandalism that flows from the White House daily.” His summing-up argument, succinctly, was, “simply put: We may have hit rock bottom.” Perhaps echoing his own decision not to seek re-election, Flake advised, “You can go elsewhere for a job, but you cannot go elsewhere for a soul.”

At the least political occasion, the celebratory dinner for honorands and University guests Wednesday night in Annenberg Hall, Corporation senior fellow William F. Lee toasted Faust for leading Harvard through unprecedented challenges with “courage, grace, and deep institutional conviction.” She, in turn, thanked those who made her job possible, and a joy, asking each in turn to stand: members of the governing boards; “my beloved Council of Deans, my academic cabinet”; departing deans Liz Cohen, James Ryan, and Michael Smith; and her Mass Hall team. She then focused on “my interlocutor, my defender, my resident faculty voice”—Charles Rosenberg, Monrad professor of the social sciences emeritus, a distinguished historian of science, and her husband—who, she continued, was always ready with a deflating quip to offset creeping grandiosity. He received a robust, appreciative ovation. After her remarks about the honorands (see below), Faust offered a final toast “to my esteemed friend and successor, Larry Bacow.”

Elsewhere, in a distinctly low-key, academic way, messages were sent about the condition of the world beyond campus. For example, the GSAS conferred one of its Centennial Medals on Guido Goldman ’59, Ph.D. ’70 (profiled here, with his fellow honorands), noting that he fled Nazism with his family in 1940 and immigrated to the United States (traits they held in common with the parents of the University’s president-elect, Lawrence S. Bacow)—very unfashionable in the current environment for immigrants. Once established, he became (gasp, given the current state of transatlantic relations) a full-fledged Europeanist. With Henry Kissinger ’50, Ph.D. ’54, he helped develop the precursor to the Gunzburg Center for European Studies—the first U.S. university center devoted to the study of Europe; Goldman was founding director for 25 years.

Finally, there was the presence at the College’s Class day of Jin Park ’18, this year’s orator: an undocumented student whose parents are Korean immigrants working in restaurants and nail salons in New York.

Remembering 1968

This is the fiftieth-reunion year of the College class of 1968: the first undergraduates to choose their own Class Day speaker, Martin Luther King Jr., only to see him assassinated in April (read Harvard Alumni Bulletin’s coverage here). At their invitation, his widow, Coretta Scott King, spoke in his place on June 12—six days after the assassination of presidential aspirant Robert F. Kennedy ’48 (whose seventieth reunion this would have been). In her remarks (read the text here), the recently widowed King, reflecting on the American crisis of race, said:

For me, as for millions of black Americans, there is a special dimension to our national crisis. We are not only caught up in all the evils of contemporary society, we are its lowest and most deprived component. For most of us this is not a society of abundance but a society of want. We are not newly victimized by the loss of identity and alienation. We have suffered an imposed heritage of exclusion and frustration for generations. Our future is doubly bleak as we face the unabated racism and deepened deprivation reserved for black Americans.

Perhaps reflecting the youth of both her audience and of her murdered husband (39 years old) and Kennedy (42), she said:

There is reason to hope and to struggle if young people continue to hold high the banner of freedom.…It is time for both fresh ideas and new leadership to come forth, because without it our society is on sinking sand.…

[I]n struggling to give meaning to your own lives, as students you are preserving the best in our traditions and are breaking new ground in your restless search for truth. With this creative force to inspire all of us we may yet not only survive—we may triumph.

On vivid display in the University Archives’ “Harvard, 1968” exhibition at Pusey Library are many resonant echoes of that era—a time of tensions that tore society apart in ways that present circumstances do not approach: confrontation with North Korea over the seizure of the U.S.S. Pueblo in January; the Beatles’ “Revolution” and Simon & Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson” succeeding earlier, lighter music; student demands (reproduced here), in the wake of the King assassination, for appointments of black faculty members, creation of a black-studies program (inaugurated in 1969), and admission of students in proportion to their representation in the population; a draft-resistance advertisement in the Crimson (and an earlier interview with government professor Samuel P. Huntington, a supporter of the war in Vietnam, by Crimson journalist Linda Greenhouse ’68—subsequently an Overseer and now a leader of her class); the memorandum on the “Proposed Change in Parietal Regulations for the Harvard Houses” (under which “Lady guests may be entertained in student rooms” at specified hours—a change adopted for the next academic year); and Radcliffe students, graduating in Radcliffe Yard, wearing white armbands with their gowns, to protest the war and mourn the slain leaders. There is also an archival video recording of Coretta Scott King’s address.

Not in the exhibition, but useful as a sign of those contested times, was Arthur S. Lipkin’s Class Ode, delivered right after King spoke. Playing bitterly with the cadences and meter of “Fair Harvard,” Lipkin recited, “Our ritual laughter is stifled and bleak;/Our headiness fades with its cry./On this day, like others, we ponder a war/Where friends died and more friends will die.” He concluded, “The nation that greets us is tortured and sick/And mouths inarticulate cures./We pray for the spirit to cope with a world/Where so very little assures.” (It may be of some comfort to traditionalists upset with the newest modification of “Fair Harvard”—swapping “Till the stock of the Puritans die” for “Till the stars in the firmament die” and sung for the first time during the Tuesday Phi Beta Kappa ceremony—that the changes, and underlying causes for making them, are less high stakes than those in play a half-century ago. Read about Janet Pascal ’84 and how she crafted the new line here.)

Many of these images and events and issues remain alive for the class members, who took note of them in a special performance. They also remain vivid for Faust, their Bryn Mawr contemporary; in a special greeting at the front of the gargantuan College class’s reunion report, she writes, “There were no halcyon undergraduate days for those of us who graduated in 1968,” and recalls the period running from Tonkin Gulf to the assassinations that spring. “In 1968,” she wrote, “the odds of my becoming the president of Harvard University and Bob Dylan’s being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature were approximately the same.” Now Faust, who engaged directly in the civil-rights movement as an undergraduate, has summoned its energy—and unfinished agenda—in her choice of John Lewis as the guest speaker for the afternoon ceremonies at her last Commencement exercises as president.

Not everyone enrolled then can come back for reunion, of course. Carl Thorne-Thomsen ’68, profiled here, chose to withdraw from Harvard, was drafted, and died in combat in Vietnam in October 1967.

Thursday Morning: The Students Speak

At 9:15 a.m., the President's Division reached the Commencement platform in front of Memorial Church: Faust, Bacow (still a Corporation member), and then the provost, Alan Garber, and the senior fellow, William Lee. Also present on the platform was former president Lawrence H. Summers, now Eliot University Professor (and father of Ruth, among the Graduate School of Education degree candidates in the audience below).

A bit behind schedule (read the program for the Morning Exercises here), at 9:55, the showboatin’ sheriff of Middlesex County, Peter Koutoujian, M.P.A. ’03, called for order and, as is customary, shattered 64,000 or so eardrums.

Khalil Abdur-Rashid

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Following the singing of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the chaplain of the day, Khalil Abdur-Rashid, who became the University's first full-time Muslim chaplain last summer, offered the opening prayer, invoking “tongues that speak truth to power,” and urging the audience to “estrange those who reject love.”

Bowing once more to the wisdom and all-around sterling qualities of newly educated youth, Harvard gives the choice speaking parts, morning edition, to students (the older voices get their audience after lunch). This year’s speakers—the last coached by the estimable Richard J. Tarrant, Pope professor of the Latin language and literature, who is retiring (read aboout their work together, preparing for today’s presentations)—include a pair of Kirkland House residents and a Harvard Law School student: Phoebe Madeleine Lakin ’18 (the Latin Salutatory and its English translation); Christopher Ebunede Egi ’18 (the Senior English Address), and Pete Davis ’12, J.D. ’18 (the Graduate English Address). After a brief microphone malfunction, Faust did the introductions, beginning with Lakin.

“Experientia Transfigurativa” (“A Transfigurative Experience”): Latin Salutatory

Ten years after J.K. Rowling lit up Tercentenary Theatre with a memorable Commencement afternoon address, Phoebe M. Lakin drew on Harry Potter and Hogwarts to decipher her Harvard experience.

An Adirondacks native, Lakin grew up in Ithaca, New York. “I’ve studied Latin since I was nine,” she writes, “and fell in love with it early on, thanks to my brilliant and dedicated Latin teacher, who taught me…from fourth grade through high school.” She carried that passion to the College, concentrating on Latin and ancient Greek (but not confining her interest in languages too narrowly: she has also studied French and German). In her research, she writes, “I have focused on the interweaving of the natural world and the written word, interests that I brought together in my senior thesis, in which I examined a poem on gardens written in Latin in the first century A.D. My interests extend to archaeology, and I was able to work on an excavation near Oxford the summer after my freshman year. Since sophomore year, I have interned and then worked at the Harvard Semitic Museum.”

Phoebe M. Lakin

Photograph by Jim Harrison

From here, she travels to the University of Cambridge to pursue an M.Phil. in Latin and Greek—plus dipping into Italian. After that? A doctorate in the classics. In her spare spare time, Lakin indulges in hiking and kayaking, and terms herself a passionate environmentalist.

Her oration, she says (read her full text, in Latin and English, here), “places some of the meaningful moments of my time at Harvard into the context of a work of literature. Parts of the speech are lighthearted, but I hope to convey a sense of the substantial personal transformations that we've undergone during our studies here.” The references to Harry Potter, she notes, provide “a concrete example of the enduring importance and universality of literature. When we read, enjoy, and discuss books, they help us make sense of the world and of our own experiences”—thus:

Were we not just as astounded as Harry when we received our acceptance letters, delivered not by owl but—incredibly—upon the wings of email? Have we not spent our nights brewing potions in the Science Center, as though in the Dungeons? Did we not often greet the dawn among the bookshelves of the Restricted Section—that is to say, Lamont Library?

She and her peers, schooled in the magical arts,

Relying on our newfound knowledge, as if upon magic wands, wecan transform cells into tissues and translate English into Python, speaking to snakes, as did Harry himself. We have even transfigured Harvard during our time as students here, through our passion for asking difficult questions and our hard work. Sometimes Harvard has also changed of its own accord, like the Shifting Staircases at Hogwarts: hail and farewell, Greenhouse Café! [in the Science Center, now renovated into a jazzy commons]

Nodding toward the beginnings sense of Commencement, she concludes:

Wherever we go next, by broomstick or by automobile, the gates of the Yard will always be open for us. As the author herself once said, “Hogwarts will always be there to welcome you home.” Now farewell, my classmates, and let us go and work our magic!

“Tree of Dreams”: Senior English Address

Christopher E. Egi drew upon history—his family’s emigration from Africa to Canada, and the profound effect that Michael Brown’s death had on him in 2014, just before he arrived at Harvard—to encourage his classmates to lift their vision from personal aspiration to the dreams, so often unfulfilled, of those around them.

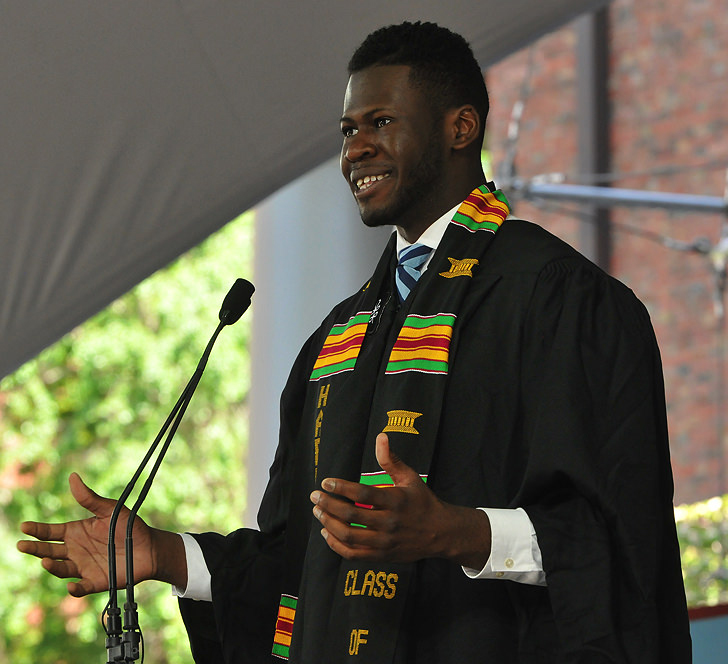

Christopher Egi

Photograph by Jim Harrison

“I was born and raised in Toronto,” Egi writes, “the child of two Nigerian immigrants” who always valued education. “This emphasis on education carried through to me and brought me to Harvard as a student athlete”—ultimately, captain of the basketball team and an economics concentrator with a secondary in African American studies (he had to bend the microphone up a lot before speaking). In his capacity as varsity athlete, Egi used his role to address issues of social conscience; as David Tannenwald reported last fall for Harvard Magazine:

Egi “has been an active participant on social media to promote inclusion, including on #unfiltered, a site created by former Harvard player Zena Edosomwan ’17 to give students a platform to, as the website says, “tell your personal truth.” In one entry, Egi wrote, “As a black male, it’s easy to believe that you amount to nothing….I want to be that guy that young black boys look up to and say, ‘If he can do it, so can I.’”

In an interview…Egi said he sees himself not as an activist but as “a conscientious citizen”—which he defined as “doing the right thing.”

“Basketball at Harvard has taught me a variety of important lessons,” Egi writes, “ranging from hard work and time management, to compassion and the ability to love and care for those around you…some of the most important lessons I learned throughout my Harvard experience. I’ve also had the privilege of managing Gold Test Prep, a tutoring company that looks to help minorities and student athletes who can’t afford test prep services.”

In his speech (read his full text here), Egi explains, “I wanted to touch a little bit on my grandfather’s grandiose dreams for success, embodied in a tree he used to climb. I wanted to use that imagery as a way of sending a message about caring for others, and helping those who are marginalized in our society to achieve their own dreams. At the center of my speech are the themes of love, awareness, and community that I hope to carry with me”—initially in finance, as he heads to Goldman Sachs after graduation, and in the longer term, engaging “in social entrepreneurship to tackle issues of access to resources for marginalized minorities.”

He began:

When my mom was a little girl growing up in the Nigerian Village of Ososo, she and her four siblings would get excited whenever one of them accomplished something noteworthy. Why? Well, it meant her dad would do the tree thing. That’s when a smile would stretch across his face as he would climb a tall tree, branch by branch, all the way to the very top. His children down below would look up at him, eyes wide, sparkling and full of joy, as he yelled out “Higher, Higher and Higher.” Though he was proud, he was also never satisfied. He had a dream that his children, and his children’s children would strive for even greater things.

After recounting his acceptance at Harvard in December 2013 and his preparation to head to campus, Egi recalls the shocking, transformative news of Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri, where his body was left to lie “under the hot Missouri sun in the streets of Ferguson for eight hours. Eight hours. Just like me, Michael was black. Just like me, Michael was 18. Just like me, Michael was preparing to go to college.”

He remembers realizing:

After spending my life believing that my grandfather’s dream meant educational attainment, the accumulation of accolades or even acceptance to Harvard College, Michael Brown’s death woke me up. It made me realize that the dream was about much more than how high in that tree we could go as individuals. It was also about how we could encourage and enable those like Michael Brown, whose dreams are deferred and denied, to climb with us. And while education might be essential to achieving that dream, we often forget it is an incomplete answer.

Accordingly,

[W]hile we strive for our dreams, using the privileges that our Harvard education affords us, we can’t forget just how many other dreams have been deferred, denied, and left to dry like a raisin in the sun.…

[T]oday, I stand before you as a proud grandson of a Nigerian carpenter, the child of two Nigerian immigrants, and a graduate of one of the greatest institutions in the world—proof that while we all have dreams, some of us must travel farther to achieve them, both figuratively and literally. My wish is that with our help more dreams can be converted into realities.…Your future, my future, and the future of our society depends on us creating, supporting, and investing in the dreams that the next generation can live up to and build upon. It depends on us looking one another in the eye and helping one another to continue to strive for more. To keep growing. And to never, ever stop climbing. Because the next generation is watching, looking up at us, eyes wide, sparkling and full of joy, as we yell out, “Higher, Higher, and Higher.”

“A Counterculture of Commitment”: Graduate English Address

Pete Davis, a native of Falls Church, Virginia, who graduated from Harvard College in 2012 (he was a government concentrator) and subsequently worked at the iLab and then on labor issues with Ralph Nader, LL.B. ’58, is completing his law degree. While at the law school, he was a vigorous proponent of public-interest law, running the Harvard Law Forum, which brought speakers to campus, and publishing a bicentennial call to action focused on the school’s public-service mission. Consistent with this personal commitment, his speech makes the case againstkeeping one’s options open, and for dedicating oneself to a worthwhile cause. He traces his own commitments to his parents, Ralph Nader, and the “two professors who influenced me the most during my time at Harvard—Robert Putnam and Roberto Unger”—who

have spent their careers dedicated to the slow but necessary work of deepening and propagating big ideas. Putnam’s big idea: the importance of community (social capital) in the functioning of society. Unger’s big idea: the importance of deepening democracy—strengthening, equipping and opening up power to the constructive genius of ordinary citizens.

Davis is returning to Virginia, where he will work on building community and deepening democracy, in part by “generating and experimenting with projects that help bring neighbors together—projects that turn strangers into neighbors and spaces into places” and by pursuing “policies that strengthen citizens and communities and open up our economy and our government to the participation of more people in more ways.”

Pete Davis

Photograph by Jim Harrison

In his address (read his full text here), Davis takes head-on students’ inclincation to structure their lives as if it were, so to speak, always shopping week, with commitments deferrable indefinitely into the future. He begins with an image perhaps as familiar to this generation as the Harry Potter references in Lakin’s address—and proceeds rapidly in a no-nonsense direction:

[I]t’s late at night and you start browsing Netflix looking for something to watch. You scroll through different titles—you even read a few reviews—but you just can’t commit to watching any given movie. Suddenly it’s been 30 minutes and you’re still stuck in Infinite Browsing Mode, so you just give up—you’re too tired to watch anything now, so you cut your losses and fall asleep.

I have come to believe that this is the defining characteristic of our generation: Keeping our options open.…I’ve been thinking about this recently because leaving home and coming here is a lot like entering a long hallway—you walk out of the room in which you grew up and into this place with thousands of different doors to infinitely browse.

Summoning his undergraduate and professional-school experiences, he interprets the upsides of freedom from commitment—and its opposite:

I’ve seen all the good that can come from having so many new options. I’ve seen the joy a person feels when they find a “room” more fitting for their authentic self. I’ve seen big decisions become less painful, because you can always quit, you can always move, you can always break up… and the hallway will always be there. And mostly I’ve seen all the fun people have had experiencing more novelty than any generation in history ever experienced.

But as I’ve grown older here, I’ve also started seeing the downsides of having so many open doors. Nobody wants to be stuck behind a locked door, but nobody wants to live in a hallway either. It’s great to have options when you lose interest in something, but I’ve learned here that the more times I do this, the less satisfied I am with any given option. And lately, the experiences I crave are less the rushes of novelty and more those perfect Tuesday nights when you eat dinner with the friends who you have known for a long time, who you have made a commitment to, and who will not quit you because they found someone better.

I have discovered in my time here that the people who inspire me the most are those who left the hallway, shut the door behind them, and settled in. It’s Fred Rogers recording Episode 895 of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood because he was committed to advancing a humane model of children’s television. It’s Dorothy Day sitting with the same outcast folks night after night after night because it was important that someone is committed to them. It’s not just the Martin Luther King who confronted the fire hoses in 1963, but the Martin Luther King who hosted his thousandth boring planning meeting in 1967.

Davis sees in the dual meanings of dedication—to make something holy, and to stick at something for a long time—a key to meaning:

We do something holy when we choose to commit to something. And, in the most dedicated people I have met here, I have witnessed how that pursuit of holiness comes with a side effect of immense joy.

We may have come here to help keep our options open, but I leave believing that the most radical act we can take is to make a commitment to a particular thing… to a place, to a profession, to a cause, to a community, to a person. To show our love for something by working at it for a long time—to close doors and forgo options for its sake.

Those acts of dedication can come from diverse causes, he suggests:

It is not only the bomb or the bully that should keep us up at night—it is also the garden untilled and the newcomer unwelcomed, the neighbor unhoused and the prisoner unheard, the voice of the public unheeded and the long-simmering calamity unhalted and the dream of equal justice unrealized.

To that end, “[W] we should rebel and join up with a counterculture of commitment consisting of solid people. In this age of Infinite Browsing Mode, we should pick a damn movie and watch it all the way through…before we fall asleep.”

Conferring the Degrees

The subsequent anthem, “Unclouded Day,” could not have been more apt.

The provost began the conferring of degrees by welcoming Faculty of Arts and Sciences dean Michael Smith, “with gratitude for his 11 years of distinguished service”—and then the magic of transforming students into graduates was under way. The morning’s business proceeded extremely efficiently through the Ph.D.s and various master’s degrees, and the Extension School throng. Medical School dean George Daley made the first notable addition to his formal text, adding, “Madam President, we thank you for your years of distinguished service, we thank you for your wise leadership.” No one seemed to mind the insubordination, nor to linger, subsequently, over Harvard Divinity School dean David Hempton’s reference to the “members” of Harvard College (where “Fellows” was meant, since he was addressing the Corporation). When the Law School’s new dean, John F. Manning, pronounced the ritual words about the students whose studies point them toward “promoting the rule of law,” and Faust responded about “those wise restraints that make us free,” the traditional words seemed to have a new force in 2018.

Harvard Business School’s candidates finally stirred things up when they were asked to stand. This should not be interpreted as some new unleashing of M.B.A.s' animal spirits in the wake of tax cuts or deregulation: they are always rowdy at Commencement. Dean Nitin Nohria began by addressing “Our most extraordinary Madam President….” Perhaps in competition, the subsequent professional-school cohorts amped up the noise level, too, when their turns came. Graduate School of Design dean Mohsen Mostafavi had a new trick up his sleeve, introducing the first candidates for the master’s degree in design engineering, a joint program with the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences that admitted students in the fall of 2016.

Perhaps emboldened by the teachers striking around the country, the Graduate School of Education candidates took the prize for sheer exuberant hooting and hollering. Provost Garber welcomed their departing dean “with appreciation for his distinguished service to Harvard, and best wishes for his coming leadership of the University of Virginia.” The teachers-to-be often carry, and wave, picture books. Dean Ryan, reading from his script, had it concealed within a copy of Where the Wild Things Are, by Maurice Sendak. Indeed.

In the interval between conferring the graduate- and professional-school degrees and then the eager undergraduates’, the Commencement Choir, perhaps in a nod to the guest speaker, performed “We Are…” by Ysaÿe Maria Barnwell, who was a member of the African-American ensemble Sweet Honey in the Rock from 1979 to 2013.

When the eager undergraduates' turn came, a tradition was modified. Typically, the president comes down from her (uncomfortable) chair to shake hands with the class marshals and summa cum laudes. This year, they in turn came up to the stage to shake hands with some of the honorands, and especially with Congressman Lewis.

The Honorands

The seven honorary-degree recipients (read background on each here) were heavily weighted to the arts—perhaps because bringing art and performance into the curriculum has been a priority for Faust since early in her presidency. Among them were a poet, an electronic musician, a choreographer, and a film writer and director. They were complemented by a democratizing president, a pioneering oceanographer, and a public-health leader (and favorite son).

The degrees were conferred in the following order on:

Wong Kar Wai, Doctor of Arts. The provost, in homage (and not only because it was sunny), donned shades—the honorand’s trademark fashion statement, “whose ever-present sunglasses can’t hide the brilliance of his vision,” as Garber put it (and the citation referred to “dark shades” of emotion in his celebrated films).

Sallie “Penny” W. Chisholm, Doctor of Science. At the honorands’ dinner, Faust observed that earlier in her MIT career, Chisholm, an eminent marine biologist, was Lee and Geraldine Martin professor of environmental studies—the chair once held by Lawrence S. Bacow, now Harvard’s president-elect. Garber noted her role in championing the advancement of women in science, and educating children through the Sunlight Series of illustrated books.

George E. Lewis, Doctor of Music. A “daring innovator at the vanguard of contemporary music,” in Garber’s words, Lewis is a celebrated trombonist, a pioneer in computerized music, and a leading scholar of improvisation studies, based at Columbia. “Bold voyager on sonic rivers,” the citation said in part, riffing on the name of his Voyager music software.

President Ricardo Lagos, Doctor of Laws. A leader in restoring democracy to Chile, whom Garber called “one of Latin America’s most admired leaders,” Lagos founded Chile’s Party for Democracy, Lagos served in the post-dictatorship government before serving as president from 2000 to 2006. The citation called him, in part, “devout in defense of democracy.”

Twyla Tharp, Doctor of Arts. At Barnard, she “entered the orbit of some of dance’s iconic figures,” Garber said, before setting up her own company, creating dances inspired equally by classical and modern music, capturing the endless “expressiveness of the human body” in collaborations with everyone from Mikhail Baryshnikov to Elvis Costello.

Harvey V. Fineberg, Doctor of Laws. Wednesday evening, Faust hailed him as “Harvard’s man for all seasons”—and noted that because he was instrumental in establishing the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, whose dean she became, he was in a way responsible for bringing her to Massachusetts Hall as the University’s twenty-eighth president. Garber said Fineberg’s first name might as well have been “Harvard,” given the four degrees he earned before the honorary fifth one he was about to receive. (Garber also indulged in institutional humor, noting his predecessor’s service in the “exalted academic leadership position” of Harvard University provost.)

Rita Dove, Doctor of Letters. The much-honored poet, Garber said, “is one of the nation's most luminous literary lights” and a “passionate public advocate for the literary arts.” “She draws meaning and music from everyday moments,” according to her citation.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Ordinarily, the final honorand is the guest speaker at the afternoon exercises. This year’s speaker, U.S. Representative John Lewis, LL.D. ’12, presciently beat the crowds, picking up his degree a half-dozen years ago. At the celebratory dinner on Wednesday evening, Faust emotionally welcomed him as “an American hero, my hero.” This morning, Faust hailed him for “a life of singular and relentless devotion” to freedom, equality, and justice, and then conferred a different sort of honor, as Harvard College students, led by the composer, performed an especially apt song for Lewis: “Sing Out/March On,” a work by Joshuah Brian Campbell ’16 (who both spoke and sang during his own Commencement week (as Senior English orator, and as the musical entertainment at the dinner for honorands the evening before). A version of the song is available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5foKs7suPaU .

Finis

Photograph by Jim Harrison

In a final departure from the script, preceding the closing announcements, Garber said, “Before we conclude, I note that this ceremony marks Drew Faust’s eleventh and final” time presiding over the Morning Exercises. “Words cannot adequately express our gratitude for her extraordinary leadership,” he continued, and so he invited applause to do that work. There was plenty. As Faust put her hand over her heart, Bacow, to her right, nodded and applauded, and then, as he seemed to tear up, president and president-elect embraced—and applauded each other.

In his benediction, Jonathan Walton, the Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church, told the class of 2018, “We don’t have time to get weary in our well-doing,” and admonished them to resist the “lullabies of our own entitlement,” before sending them off to do good.

The University is throwing a community farewell party for President Faust on June 28—but after the Noah’s Ark conditions that prevailed in 2017, it would be hard to top this year’s perfect Commencement day, with Harvard at its loveliest, as a parting gift.