Allston Updates

Boston authorities have approved construction of Harvard’s 9,000-square-foot, temporary “ArtLab” near the corner of Western Avenue and North Harvard Street. The facility will be sited to the west of the cluster of innovation spaces that have sprung up at the edge of the Business School campus, but is conceived in the same spirit. Construction is expected to take about one year (as reported here).

On a far more consequential scale, the preliminary filing for the commercially oriented “enterprise research zone” (unveiled in December), outlines two office and laboratory structures totaling 400,000 square feet; a 250,000-square-foot hotel/conference center; and a similarly sized apartment tower. They would occupy part of 14 acres along Western Avenue, opposite the business school—between the science and engineering complex now rising and the existing Genzyme manufacturing center. The rest of the site would be surface parking lots, at least temporarily. Harvard did not identify a private developer for the project. Plans for the rest of the 36 acres envisioned for the zone, and for the more extensive Harvard landholdings underneath and south of the Massachusetts Turnpike intersection, which is to be reconstructed, were not put forward—a disappointment to some Allston residents. Another concern is the state’s delay, until 2040, on a mass-transit hub for the area. Further details on the filing appear here. An update on Harvard’s January offer to jump-start the transportation hub by contributing as much as $50 million to the needed financing appears here.

Down river, in the booming Kendall Square neighborhood around MIT (the sort of technology-academia hub Harvard’s planners may envision), the announcement that a supermarket would soon move into One Broadway signaled the area’s increasing appeal not only to life-sciences and information-technology tenants, but to their employees, who are taking up residence. MIT plans further intensive commercial growth in the area, including more than a thousand housing units plus offices and laboratories on a 14-acre site for which it has recently gained planning and development approval.

Overhauling Advanced Standing

At the December 5 Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) meeting, dean of undergraduate education Jay M. Harris (see “University People”) outlined proposals to eliminate the College’s policies on advanced standing. One element of the proposal proved uncontroversial: students should no longer be allowed to receive Harvard College credit for Advanced Placement (AP) examinations associated with their high-school courses, given the dissimilarity of aims and demands between those courses and their classes in Cambridge. (AP exams would still be used as measures to guide placement into College courses appropriate for each student.) Effecting this change would also, in a way, be a bow toward equity, because students from high schools with lesser resources and fewer course offerings arrive at Harvard less likely to have accumulated AP credits.

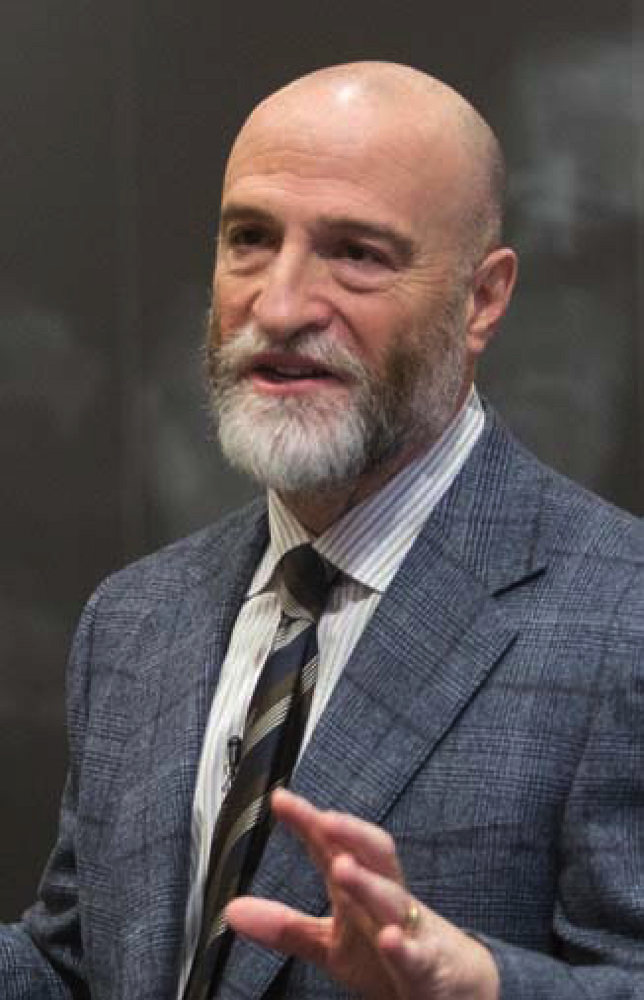

Jay Harris

Photograph by Jon Chase/HPAC

But two implications of the proposal were of concern to faculty members. Using AP courses has been the sole channel to advanced standing, enabling students to complete their undergraduate studies in six or seven semesters, or to pursue a master’s degree in their fourth Harvard year.

Harris observed that with financial aid, low-income students do not bear the cost of tuition and fees during a fourth year in residence. But some faculty speakers observed that some students wish to graduate in fewer semesters because of constraints on their health, or because of the pressing need to begin earning a full-time income to support their families—significant opportunity costs not captured in the grant of financial aid during a fourth College year.

More speakers, particularly from the sciences—computer science and physics among them—said that withdrawing the option to obtain advanced standing during an AP-eased fourth year would severely disadvantage Harvard in recruiting the most outstanding students in those fields, for many of whom the dual-degree option is a compelling attraction. The proposal Harris outlined—permitting any student capable of advanced work to pursue a master’s degree within four years of residence, but no longer allowing a reduction in College requirements (other than allowing a maximum of two courses to be counted toward both the bachelor’s and master’s degree, so earning two degrees would require a minumum of 38 courses or 152 credits)—did not alleviate those concerns.

One further element was not aired during the faculty meeting. The proposal suggests that students should continue to be allowed to fulfill their foreign-language requirement with a score of 5 on an AP exam. But the committee that drafted the report also noted that “policies around the language requirement should be reviewed.” Presumably, many high-school language courses, focused on acquiring skills and proficiency, also fall short of many College courses, which aim at “a broader cultural experience, and the kind of critical intercultural inquiry that further supports the core intellectual mission of the College.” (Maintaining the AP exemption also maintains the inequity imposed on students from under-resourced high schools.)

The proposal as a whole was advanced in December for informational purposes and initial discussion; it returns to the faculty for further airing, possible modification, and a vote in the spring term.

Doctoring the Medical School

George Q. Daley

Photograph by Stephanie Mitchell/HPAC

In his 2017-2018 report, Harvard Medical Dean George Q. Daley noted a $44-million operating deficit for the fiscal year ended last June 30, and promised that in the current year, “several major initiatives will help improve our long-term financial performance. These involve cultivating philanthropy and further evaluating the school’s real estate portfolio.” On the latter point, it is selling a 99-year lease interest in the Harvard Institutes of Medicine laboratory building at 4 Blackfan Circle, which the school acquired and renovated in 1994 and where it is now a tenant, along with two Harvard-affiliated hospitals. Although the school’s analysis obviously projects a value for the transaction, details are being kept private until a transaction closes, perhaps late this spring. Harvard will remain a tenant in about 20 percent of the space, and sublease other parts of the building to other users. The proceeds may be applied to reduce the school’s debt, fortify its endowment (strained by the operating losses), or fund research. The adjacent New Research Building, where the medical school uses more than half the space, was considered a strategic asset and was therefore not put on the market. To effect other economies and accommodate growing demand for research space, several projects under way on the core Longwood campus aim to reconfigure corridors and underutilized areas and “densify” labs. For any announcements about philanthropy of school-wide significance, stay tuned.