Reclaiming “What We Know about Life”

MIT’s Mauzé professor of the social studies of science and technology, Sherry Turkle ’69, Ph.D. ’76, a critic of social media, titled her Phi Beta Kappa oration “How Technology Makes You Forget What You Know about Life.” “Curated” conversations by social media and email, stripped of the “boring bits” and the frustrations of human discourse, may be technologically efficient, but they are shorn of human efficacy and empathy, she argued. “For the failing connections of our digital world,” she said, “conversation is the talking cure.” From her conclusion:

Sherry Turkle

Photograph by Jim Harrison

We need to reclaim what we know about life. When we reclaim our attention, our solitude, and our friendship, we will have a better chance to reclaim our communities, our democracy, and our shared common purpose. We had a love affair with a technology that seemed magical. But like great magic, it worked by commanding our attention and we took our attention off each other. Now we are ready, across the generations, to remember who we are: creatures of history, of deep psychology, of complex relationships, and of conversations artless, risky, and face-to-face. The choice ahead will not be easy, but perhaps neither hard nor easy, but those other opposites of easy: complex, evolved, and demanding. It’s time to make the corrections, and take stock of all the skills we’ll need—and of how little technology is going to help us unless we remember all the things we know about life and living.

Former U.S. vice president Joe Biden, the College’s Class Day speaker, was relentlessly optimistic about the prospects for the country, even as he disagreed with current political and policy decisions. But he noted that the class of 2017 had an obligation it could not shirk:

“Just this week, the Crimson reported that 37 percent of your class who had been considering a job in the federal government changed your minds in the wake of last year’s election. Forgive me, but I think that’s the wrong reaction. You have an obligation to get engaged. You have the capacity to make things change. It’s within your wheelhouse to do it.”

He concluded with an admonition from his former philosophy professor:

As if I was supposed to know, he said, “Remember what Plato said, Joe.” And I was thinking, what in the hell does that mean? Plato said, “The penalty that good people pay for not being involved in politics is being governed by people worse than themselves.” Let me say that again. The penalty that good people pay for not being involved in politics is being governed by people worse than themselves. So you have to engage. You have to be involved, even in this dirty business of politics, you have to, for your own safety’s sake. And I have no doubt you will, because you must.

“The World Can Be a Scary Place”

Auguste (Gussie) Jennings Roc

Photograph by Jim Harrison

In “When We Fall in One Piece,” Senior English orator Auguste (Gussie) Jennings Roc ’17 spoke of what she’d learned from two terrifying experiences—being blown out of her Lower Manhattan apartment, on the first day of first grade, by the cataclysm of 9/11; and having her Harvard Visitas weekend shut down by the manhunt after the Boston Marathon bombing—and from the kindnesses shown in each case: that “love and courage trump hate and destruction.”

I have learned that the world can be a scary place. But I have also learned that: in the face of fear, we have a choice. Who will we choose to be when we are presented with the opportunity to care about, to stand with, to speak up for, to give up something of ourselves as a simple act of humanity? Many of us have gone to bed in fear—fear of discrimination, fear of deportation, fear of walls and bans and rollbacks. We have been afraid. But, among us are the courageous. I know because I’ve seen it. I’ve eaten next to it in the dining hall, I’ve studied across from it in the library, I’ve walked by it in Harvard Yard. I know the mark of courage, and I’ve seen it here with you.

So, as we prepare to graduate and walk through those gates one final time as students, let us choose our weapons wisely. Let Courage be our defense against cowardice, Hope our defense against despair, Compassion our defense against destruction.

Let’s choose Love as our ultimate defense against fear, because in the face of fear, lies the golden opportunity to shift the narrative by being someone who is willing to walk a six-year-old to a safe place, through a hole in a chain-link fence.…

On Being “Bewildered at Harvard”

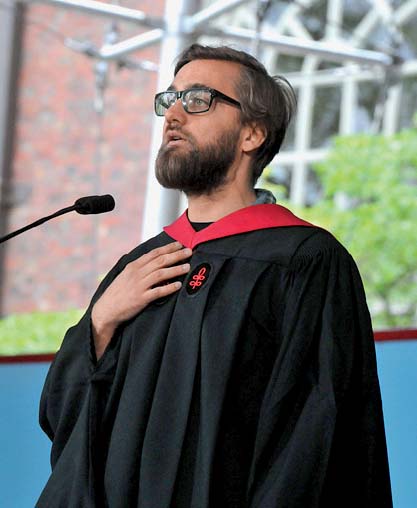

Walter Edward Smelt

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Graduate English orator Walter Edward Smelt III, M.T.S. ’17, gave an address that was seemingly about his love of books and libraries. But he took a different direction, toward a larger meaning—and along the way drew upon a source that might seem subversive in an age of immigration bans and border walls. An excerpt:

[S]ome problems just come with being human, and they need to be confronted again by each generation. No new technology, no printing press or app, is going to settle the problem of greed, or death, or hate. And at the Divinity School, we think about these problems, and about how people have dealt with them through the ages, and how to do what right we can in the face of all that’s wrong.

As it happens, that reminds me of a line from Rumi. “Sell your cleverness and buy bewilderment.” Harvard graduates will change the world, one way or another, because we’re clever. But we must be more than that. We must be willing to become bewildered: neither approaching a problem arrogantly, sure that we already know the answer, nor throwing up our hands and walking away. Becoming bewildered means admitting some problems don’t have quick fixes. It means learning from mistakes, learning from the other, learning what it is we can’t learn.

And those are things Rumi can teach us about. Rumi, an immigrant from what is now Afghanistan to what is now Turkey, an immigrant from the thirteenth century to our own, a Muslim mystic. Rumi has something immensely valuable to tell us, but we have to listen really hard for it, with humility, and for the rest of our lives.

…[A]fter a few years here, I’m sure you’ll agree that knowledge is hard. But wisdom is even harder. We’ll need both…because this world is complex and contradictory, and if we’re not bewildered sometimes, we’re doing it wrong. But we’ll go forth anyway, to change the world and also to be changed by it, to write our own books. Those books may be made of paper or published digitally, or…may simply be the legacy of the acts that make up a life. Regardless of their form, your books will be good books if you are willing to be bewildered, if you take on this messy, tragic, lovely world and confront its problems in good faith.

President Drew Faust

Photograph by Jim Harrison

In her Commencement afternoon remarks, President Drew Faust talked about free speech. She was mindful that “recently, we can see here at Harvard how our inattentiveness to the power and appeal of conservative voices left much of our community astonished—blindsided by the outcome of last fall’s election. We must work to ensure that universities do not become bubbles isolated from the concerns and discourse of the society that surrounds them.” But she was also concerned about other aspects of speech on the contemporary campus. An excerpt:

Campus conflicts over invited speakers are hardly new.

Yet the vehemence with which these issues have been debated in recent months not just on campuses but in the broader public sphere suggests there is something distinctive about this moment. Certainly these controversies reflect a highly polarized political and social environment—perhaps the most divisive since the era of the Civil War. And…free-speech debates have provided a fertile substrate into which anger and disagreement could be planted to nourish partisan outrage and generate media clickbait. But that is only a partial explanation.

Universities themselves have changed dramatically in recent years, reaching beyond their traditional, largely homogeneous populations to become more diverse than perhaps any other institution in which Americans find themselves living together.…Harvard College is now half female, majority minority, religiously pluralistic, with nearly 60 percent of students able to attend because of financial aid.…[Yet many] of our students struggle to feel full members of this community…in which people like them have so recently arrived. They seek evidence and assurance that—to borrow the title of a powerful theatrical piece created by a group of our African-American students—…they, too, are Harvard.

The price of our commitment to freedom of speech is paid disproportionately by these students. For them, free speech has not infrequently included enduring a questioning of their abilities, their humanity, their morality—their very legitimacy here. Our values and our theory of education rest on the assumption that members of our community will…actively compete in our wild rumpus of argument and ideas. It requires them as well to be fearless in face of argument or challenge or even verbal insult. And it expects that fearlessness even when the challenge is directed to the very identity—race, religion, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, nationality—that may have made them uncertain about their right to be here in the first place. Demonstrating such fearlessness is hard; no one should be mocked as a snowflake for finding it so.

Hard, but important and attainable….But the price of free speech cannot be charged just to those most likely to become its target. We must…nurture the courage and humility that our commitment to unfettered debate demands from all of us. And that courage means not only resilience in face of challenge or attack, but strength to speak out against injustices directed at others as well.

Mark Zuckerberg exhorted the Tercentenary Theatre crowd (and several million Facebook followers) “to create a world where everyone has a sense of purpose: by taking on big meaningful projects together, by redefining equality so everyone has the freedom to pursue purpose, and by building community across the world.” The scope of the challenges he identified would fit well with Joe Biden’s exhortation for Americans to think big; on equality alone, he said:

We should have a society that measures progress not just by economic metrics like GDP, but by how many of us have a role we find meaningful. We should explore ideas like universal basic income to give everyone a cushion to try new things. We’re going to change jobs many times, so we need affordable childcare to get to work and healthcare that aren’t tied to one company. We’re all going to make mistakes, so we need a society that focuses less on locking us up or stigmatizing us. And as technology keeps changing, we need to focus more on continuous education throughout our lives.

Acknowledging the current distemper, he said:

[W]e live in an unstable time. There are people left behind by globalization across the world. It’s hard to care about people in other places if we don’t feel good about our lives here at home. There’s pressure to turn inwards.

This is the struggle of our time. The forces of freedom, openness, and global community against the forces of authoritarianism, isolationism, and nationalism. Forces for the flow of knowledge, trade, and immigration against those who would slow them down. This is not a battle of nations, it’s a battle of ideas. There are people in every country for global connection and good people against it. This isn’t going to be decided at the UN, either. It’s going to happen at the local level, when enough of us feel a sense of purpose and stability in our own lives that we can open up and start caring about everyone. The best way to do that is to start building local communities right now.

And with barely controlled emotion, he related this story from one of his own communities: Remember when I told you about that class I taught at the Boys and Girls Club? One day after class I was talking to them about college, and one of my top students raised his hand and said he wasn’t sure he could go because he’s undocumented…. Last year I took him out to breakfast for his birthday. I wanted to get him a present, so I asked him and he started talking about students he saw struggling and said, “You know, I’d really just like a book on social justice.” I was blown away. Here’s a young guy who has every reason to be cynical. He didn’t know if the country he calls home—the only one he’s known—would deny him his dream of going to college. But he wasn’t feeling sorry for himself. He wasn’t even thinking of himself. He has a greater sense of purpose, and he’s going to bring people along with him. It says something about our current situation that I can’t even say his name because I don’t want to put him at risk. But if a high-school senior who doesn’t know what the future holds can do his part to move the world forward, then we owe it to the world to do our part too.