Updated 9-24-14; see below.

HIGHLIGHTS:

- The endowment's value stood at $36.4 billion as of June 30 (within a half-billion dollars of the peak value realized in fiscal year 2008, just before the financial crisis and ensuing recession), up $3.7 billion (11.3 percent) from $32.7 billion a year earlier.

- Amid continuing strength in world financial markets, Harvard Management Company records 15.4 percent investment return on endowment assets during fiscal 2014, up from 11.3 percent return in prior year.

- Public- and private-equity assets lead positive returns (although both slightly trailed their market benchmarks); all classes of assets contribute to the endowment gains.

- Harvard’s overall performance exceeds the 14.6 percent return of its benchmark policy portfolio (its asset-allocation model) by 82 basis points. But the results trail those reported by other institutions recently (although peer universities with the largest, most similarly diversified endowments have yet to report).

Update: See report on Yale and Stanford endowment returns, below. 9-24-14, 11:00 a.m.

The University is raising a lot of money—the Harvard Campaign recorded gifts and pledges of $4.3 billion toward its announced goal of $6.5 billion as of last June 30, the end of fiscal year 2014 (and has since received hundreds of millions more). But as always, the single most significant factor in the institution’s financial position is the growth, or lack thereof, in the endowment, as even modest investment returns yield large sums in absolute terms, underpinning Harvard’s largest source of operating income: 36 percent in fiscal 2013.

That was amply demonstrated again today as Harvard Management Company (HMC) reported that the endowment’s value rose 11.3 percent, to $36.4 billion, as of the end of the fiscal year, this past June 30. The endowment had been valued at $32.7 billion at the end of fiscal 2013—so the one-year gain equals more than half the seven-year campaign’s overall goal for current-use, building, and endowment gifts. The reported result tracks closely with a back-of-the envelope calculation prepared a few weeks ago, and brings the endowment’s value tantalizingly close to its peak value of $36.9 billion, reported in June 2008, just before the financial crisis.

The growth during the year just ended represents the interaction of three factors:

- Appreciation. HMC’s in-house and external money managers earned an aggregate 15.4 percent investment return on endowment assets (after all expenses) during fiscal 2014. That produced perhaps $5 billion in gains (disregarding other transfers and timing differences that go into the final rate-of-return calculation and reported endowment value). During fiscal 2013, HMC recorded an 11.3 percent rate of return, yielding $3.3 billion in investment gains.

- Distributions. The endowment’s value is reduced by distributions to support Harvard’s operating budget, and other distributions for one-time purposes (“decapitalizations”). The operating distributions totaled $1.5 billion in fiscal 2013, and were budgeted to increase 2 percent this year. They likely grew somewhat more, reflecting distributions on various transferred funds and new monies received, so an estimate of $1.6 billion in distributions for fiscal 2014 might be in order. Decapitalizations, which vary widely from year to year, were $157 million in fiscal 2013. (Comparable figures for fiscal 2014 become available with publication of the University’s annual financial report later this autumn.)

To put the effect of the distributions on the endowment’s reported value into perspective: during the period including the fiscal years 2009 through 2013, as it increased from its post-crisis low value of $26.0 billion to $32.7 billion, shown in the exhibit below, some $8 billion was distributed to fund the University’s operating budget and decapitalizations, according to the annual financial reports. Thus, following the traumatic $11-billion decline in fiscal 2009, the endowment has in subsequent years grown back by nearly $10.5 billion after taking the distributions to Harvard into account.

- Gifts. Finally, the endowment’s value is augmented by capital gifts received for the endowment during the year. That sum totaled $223 million in fiscal 2013; it will be interesting to see whether the volume rose in the most recent year, reflecting the payoff from the quiet phase of The Harvard Campaign and its first public year. As disclosed in the annual financial reports, total pledges receivable rose 20 percent, to $909 million, in fiscal 2012, and a further 36 percent, to $1.24 billion, in fiscal 2013. (Pledges specifically for the endowment, a fraction of the outstanding balances, rose at a more gradual pace, but assuredly rose, too).

That was before the most recent fiscal year, when the fundraisers secured gifts and pledges of at least another $1.5 billion. As pledges to endow financial aid and professorships (for example, the $150-million commitment by Kenneth C. Griffin ’89) and the newly renamed Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health ($350 million), to cite just two landmark gifts, are paid, the endowment’s principal rises. A capital campaign, as its name implies, is in many ways focused on exactly such endowment-anchoring and -boosting gifts. Again, the exact figure will be released with Harvard’s fiscal 2014 financial report sometime later this autumn.

Thus, the rough arithmetic would be: $32.7 billion beginning value plus $5 billion (fiscal 2014 investment gains), minus $1.6 billion (distributions for the University budget), plus some gifts for endowment received, equal the endowment’s $36.4-billion value as of this past June 30.

This year’s returns build upon the fiscal 2013 results in a way that must give University financial planners at least a temporary sense of comfort. Since the 2008 financial crisis and resulting recession, investment returns have been very volatile, and the resulting pressure on the endowment’s value has constrained distributions to support Harvard’s operations—an important consideration in launching and framing the ambitious Harvard Campaign.

The Financial Context

As recently reported, conditions have continued to be very favorable for many categories of investments around the world.

- For equity investors, broad market indexes registered about a 25 percent gain for U.S. stocks during the year ended June 30, about 24 percent for international markets in developed countries, and about 14 percent for emerging markets.

- In the fixed-income sector, U.S. high-yield (so-called “junk”) bonds produced outsized returns of nearly 12 percent, municipal bonds about half that, and the aggregate indexes about 4 percent; global and emerging-market bond indexes showed returns of perhaps 9 percent to 11 percent.

HMC has substantial assets in these categories, as well as investments in private equity, real estate, and other holdings (see the charts above and below, and the narrative in “Harvard Performance Details,” below).

A traditional 60/40 portfolio (60 percent equities and 40 percent bonds, using broad public-market benchmarks—unlike Harvard’s and other diversified university endowments, which rely much more heavily on private assets) yielded about a 15 percent return for the year. Wilshire Associates’ Trust Universe Comparison Service—a common benchmark for endowment and foundation investors, many of whom have assets that look like the traditional 60/40 model—showed a median one-year return of 15.7 percent.

It is early in the annual reporting season (peers with large, diversified endowment portfolios including Yale, Princeton, and Stanford have yet to publish results), but the results to date are indicative of what kind of year investors had. Among higher-education institutions, the following reported these rates of returns during the fiscal year, and the resulting values of their endowments:

- MIT: 19.2 percent, $12.4 billion

- Dartmouth: 19.2 percent, $4.5 billion

- Duke: 20.1 percent, $7.0 billion

- University of Pennsylvania: 17.5 percent, $9.6 billion

- University of Virginia: 19.0 percent, $6.9 billion. (The University of Virginia Investment Management Company, which has a very strong long-term record and excellent, detailed financial reporting, highlighted exceptional results in private-equity assets, with a 35.3 percent rate of return, and natural-resources investments, up 27.1 percent, buoyed by energy assets.)

- Update 9-24-14, 11:00 a.m. Yale reported a 20.2 percent investment return, raising the value of the endowment from $20.8 billion at the end of fiscal 2013 to $23.9 billion this year, and surpassing the prior peak value of $22.9 billion at the end of fiscal 2008. Stanford has announced a 17 percent return for fiscal 2014, bringing the value of its endowment to $21.4 billion.

Among public institutions, the following offered interesting commentary on their results:

- The huge California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) reported preliminary fiscal 2014 returns of 18.4 percent—up from 12.5 percent in the prior year. It cited strength in public equities (global stock holdings, up 24.8 percent) and real estate (up 13.4 percent). Private-equity assets appreciated 20.0 percent.

- The Massachusetts state pension fund reported a 17.6 percent investment gain for fiscal 2014, up from 12.7 percent in the prior year. The investment managers cited strength in private equity, public equities, and real estate.

Harvard Performance Details

As reported when HMC president and CEO Jane L. Mendillo announced her intention to conclude her service at the end of this calendar year, Harvard’s returns have somewhat lagged those of peer institutions in recent years. That has led some analysts to suggest that, as Olshan professor of economics John Y. Campbell (a former HMC director, and a scholar of asset management) put it, the top-performing endowment in any given year is now “more a matter of luck.” He added that it would be unwise to expect Yale and Harvard always to lead the rankings.

The challenge for managers of HMC’s portfolio, and those of similarly constructed endowments, is to pursue what have been superior, long-term returns from private markets—for which higher risks are supposed to produce higher rewards—during a period of torrid performance in the more liquid, and presumably less risky, public stock and bond markets. As Mendillo noted in her 2013 report, when private-equity assets returned 11.0 percent (“well below the return” on public stocks), “When we invest in private equity, we lock up Harvard’s money for multiple years. In exchange for that lock-up we expect to earn returns over time that are in excess of the public markets—an ‘illiquidity premium.’ Over the last 10 years however, our private equity and public equity portfolios have delivered similar returns.” That performance prompted changes in investment personnel and strategy—and suggests why it is worthwhile disaggregating HMC’s reported performance in fiscal 2014 by asset class, to see how its aggregate return ended up mirroring public portfolios.

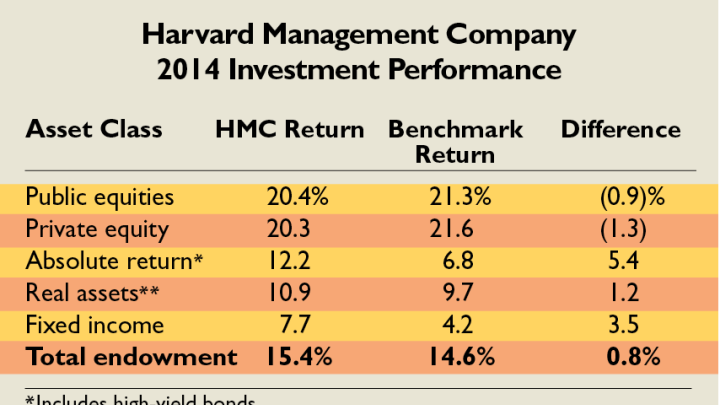

In posting a fiscal-year rate of return that exceeded its benchmark portfolio, HMC reported, it sustained a five-year record, realizing investment gains of $1.9 billion in excess of market returns during that extended period. But performance varied by sector, as follows:

Public equities. Public stock investments—about one-third of HMC’s assets—produced returns of 20.4 percent, trailing the market benchmark by 0.9 percent. Domestic equity investments returned 25.7 percent: a stronger result than the widely followed Standard & Poor’s 500 index (24.6 percent). Developed foreign-market equities returned 20.1 percent—4.1 percentage points less than the benchmark. Emerging-market equities yielded a return of 14.3 percent—exactly even with the market, and up strongly from a weak performance for such assets in the prior year.

In her comments on the year, Mendillo wrote of the latter class, “despite near-term challenges, many emerging countries are building their economies and their markets on attractive long-term fundamentals, including increased domestic consumption, better financial regulation, and improved physical and market logistics. Although our emerging markets exposure caused a nominal drag in recent years, we believe our portfolio’s allocation to this asset class will be a significant positive to future returns.”

Private equities. Private-equity and venture-capital investments (about 16 percent of the policy portfolio, up from 13 percent in the prior year) yielded a 20.3 percent return—up smartly from fiscal 2013, but 1.3 percentage points lower than the benchmark. In a new reporting format, these assets are now disclosed in three categories. U.S. corporate finance assets earned 14.1 percent, some 4.6 percentage points worse than the benchmark return; international corporate finance assets earned an 18.3 percent return, 5.3 percentage points weaker than the benchmark. Venture-capital investments, on the other hand, earned 32.8 percent, a full 10.3 percentage points better than the benchmark.

HMC remains committed to private equity, and indeed has increased its allocation to the class to 18 percent of the policy portfolio for fiscal 2015. Mendillo observed, “Private equity is one of the areas where large pre-crisis commitments and investments have continued to undercut our recent performance. For the vintage years 2004–2008, our largest commitment years, comprising 73 percent of the current portfolio, our funds are substantially underperforming. The performance of Harvard’s private-equity portfolio excluding those outsized investments is considerably better, and we are continuing to concentrate and focus our portfolio on a strong set of relationships with top managers.”

The evolution of the portfolio will apparently be gradual; in explaining the increased policy-portfolio weighting, Mendillo wrote, “We are aware that market conditions in private equity are somewhat heated today; therefore, we will take our time getting to this allocation. As a result, actual exposure to private equity may decrease in the near term before it increases.” Students of University finances may take comfort from her observation that the increased appetite for private equity reflects not only a judgment about potential returns, but also the conclusion that “while the portfolio experienced liquidity constraints over the past five to six years, the liquidity profile of the endowment is now improved, allowing us to strategically increase our position in illiquid assets.” That is the result of strenuous work to restructure the endowment and Harvard’s budget in recent years, plus the happy consequences of recent investment gains and the prospect of a rising tide of campaign gifts.

Absolute return. These assets (accounting for about one-sixth of endowment investments) yielded a 12.2 percent return: down slightly from fiscal 2013, but with another year of strong relative performance (5.4 percentage points better than the benchmark). Such assets, invested by external hedge-fund managers, are explicitly designed to operate separately from the equity portfolios, and thus do not include typical long/short stock strategies. Instead, they include a mixture of investments ranging from high-yield bonds to distressed securities, assets shed by banks that are deleveraging, and so on: meaningful diversification for HMC’s portfolio.

Real assets. HMC maintains about a quarter of its assets in this category, including natural resources (primarily timber and agricultural land), real estate, and a small commitment to publicly traded commodities (like oil and natural gas). For the real-assets category as a whole, the investment return was 10.9 percent—1.2 percentage points better than the market benchmark. Real estate, driven by HMC’s direct investments (as opposed to those made through outside investment managers) again produced strong results, yielding a 13.0 percent return (ahead of the 12.0 percent benchmark return). A new exhibit separates recent (since 2010) direct investments, with a 20.4 percent return, from legacy assets (“in run-off mode”), which produced a 7.8 percent return. Natural resources returned 9.0 percent, 1.5 percentage points better than the benchmark. And public commodities returned 8.6 percentage points, somewhat below market returns.

In the exhibit on HMC’s asset-allocation model in Mendillo’s letter, public-commodities investments, shrinking in importance since 2008, are shown as being eliminated for fiscal 2015, given their changed performance characteristics. Overall, the fiscal 2015 policy portfolio also gives more weight to real estate and less to natural resources.

Fixed income. Although HMC does not emphasize bond investments—and has progressively reduced such holdings to about 10 percent of assets, while increasing growth-oriented equities of various sorts—its internally managed portfolios often perform strongly. In fiscal 2014, HMC’s fixed-income returns overall were 7.7 percent (some 3.5 percentage points above the market benchmark). Domestic, foreign, and inflation-indexed bond returns were all positive, with domestic assets earning 6.9 percentage points more than the benchmark, and foreign bonds outperforming by 10.0 percentage points.

Characterizing the year, Mendillo said in a news release, “We are pleased to continue to deliver substantial financial support for Harvard’s academic, financial aid, and research programs. We have delivered a five-year average annual return of 11.6 percent, which is consistent with the long-term returns HMC has delivered over the last 10, 20, and 40 years. Our organization and our portfolio are now well positioned to continue to deliver substantial returns and cash flow to the University for decades to come.” (Connoisseurs of financial reporting will welcome the return of five-year performance data in her report; they had vanished in recent years, when three- and 10-year returns were shown. The new figures capture the rebound from the endowment’s low point at the end of fiscal 2009, when the financial crisis punished most investors, and Harvard especially.)

HMC board chair James F. Rothenberg—a member of the Harvard Corporation, co-chair of The Harvard Campaign, and former University treasurer—said in the release, “Jane and the HMC team have done an excellent job strengthening the portfolio and investment organization, and we are proud to deliver strong returns to the University.” Drawing on a “cost-of-management” study cited in Mendillo’s letter, he said, “At the same time, HMC’s unique hybrid model has saved the University approximately $2 billion over the last decade as compared to the cost of management for a completely external model.”

Outlook

In a personal farewell note, Mendillo concluded her report in a positive vein:

The future is once again bright for HMC and the Harvard portfolio and, in that context, earlier this spring I announced my decision to step down as CEO at the end of the calendar year. I have spent 22 years at the Harvard endowment, in a wide range of roles, and I can’t imagine a better way to spend a career or a more noble cause. It was six years ago this month, September 2008, that I published my first letter as CEO to our alumni community. At that time Harvard University was facing an exceptionally challenging environment as the financial crisis swept through global markets. Six years later it is a completely different story and I am very proud of what we have accomplished. We have recovered from the crisis, generated double-digit investment returns, repositioned the portfolio with adequate liquidity, helped the University to enhance its financial footing, and strengthened the HMC team and outside relationships with some of the best investment managers in the world.

Taking an unusually expansive view of the future, she closed by writing:

Looking forward, HMC is well positioned to continue to deliver double-digit annual returns over the next 40 years, as we have done over the last 40 years, enabling Harvard University to pursue its inspiring and world-changing academic and research objectives. It will be exciting to watch.

Getting a start on realizing those returns, in the current, uncertain markets, will be the responsibility of Mendillo’s successor, whose appointment is expected before her departure at the end of the semester.

Read the University news release here.