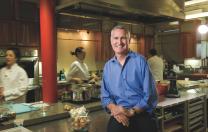

“I come from three generations of Jewish bakers,” says David Eisenberg, Osher distinguished associate professor of medicine. “I grew up cooking and with a great appreciation for food as a powerful, celebratory aspect of life. We forget that at our peril.” Eisenberg (see “The New Ancient Trend in Medicine,” March-April 2002, page 46) sees himself as an ambassador between the food and culinary community and the medical profession, which is sworn to prevent, treat, and manage disease. “I think the two groups need to have a much closer relationship,” he says. “And teach one another, and create a united front.”

To that end, Eisenberg is a prime mover behind the annual “Healthy Kitchens, Healthy Lives” (healthykitchens.org) course that the Medical School’s Osher Research Center offers in partnership with the Culinary Institute of America (CIA). For four days each April, at the CIA’s facility in Napa Valley, California, 400 healthcare professionals, 65 percent of them physicians, convene to hear restaurant chefs and cookbook authors like Mollie Katzen explore the subtleties of legumes, vegetables, and spices; learn about menu planning and the relationship of whole grains to blood glucose levels; and savor some highly flavorful, healthy meals. Much of the food they cook themselves; it’s a hands-on course taught by professionals. “We have some of the most masterful chefs in America,” Eisenberg says, “showing us how to make, say, five different delicious dishes in five to 10 minutes apiece.”

There are sessions on prescribing exercise and counseling patients on nutrition, but the main thrust is leading by example. “We know for a fact, based on medical literature, that clinicians’ personal behavior is the strongest predictor of their providing advice on that same behavior to patients,” Eisenberg says. “Doctors who have quit smoking, who exercise, wear seatbelts and sunscreen, counsel their patients more on these things. What if physicians accepted it as part of their responsibility to think about food differently?”

“Most of these clinicians don’t know cooking skills,” he reports. “They barely know how to hold a knife—we’ve had to create knife-skill workshops. If you can’t use a knife in the kitchen, and if your parents and grandparents never taught you to cook, you’re really starting from scratch. Most college students don’t know how to do it, either. We’ve had two generations of women who became working parents and so were not at home cooking; if women were the predominant teachers of cooking skills, we now have 20 to 30 years of people who never got those skills.”

Teaching healthcare professionals about culinary matters is one part of a fabric of change that, Eisenberg says, will have to include K-12 education, new business ventures, and scientific evidence of the significant clinical benefits of eating well. “Restaurants are not going to stop selling stuff that makes them money,” he says. “Restaurants are just serving the market. Once the demand shifts, so will the food supply.”