Among its crimes against humanity, Nazi Germany may have stolen more than five million cultural objects from the countries it conquered, including thousands of the world’s greatest artistic masterpieces. As the American and British armies and their allies began pushing back onto the Continent, an unusual front-line military unit with too few men and too little equipment accompanied them—members of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives section (MFAA). The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History, by Robert M. Edsel, with Bret Witter, narrates the background, actions, and achievements of these soldiers.

Their initial responsibility was to mitigate combat damage, primarily to structures—churches, museums, and other important monuments. As the war progressed and the German border was breached, their focus shifted to locating movable works of art and other cultural items stolen or otherwise missing.

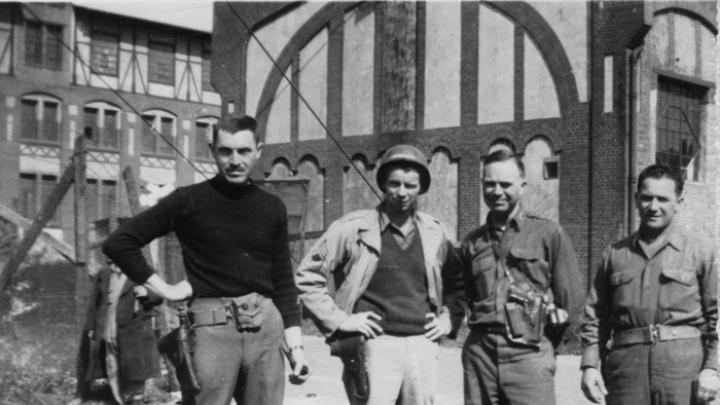

Harvard alumni played important roles in creating and staffing the MFAA, among them Paul Sachs ’00, director of the Fogg Art Museum, Mason Hammond ’25 (future Pope professor of the Latin language and literature), Lincoln Kirstein ’30 (future founder of the New York City Ballet), and James Rorimer ’27 (future director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art). But the hero of this new work is George Stout, A.M. ’29, formerly lecturer on design and conservator at the Fogg. These excerpts from throughout the book (reprinted with permission) focus on his nearly forgotten role.

George Stout was not a typical museum official. Unlike many of his peers, who were the product of the eastern elite establishment, Stout was a blue-collar kid from the small town of Winterset, Iowa. From there, he went straight into the army, where he served during World War I as a private in a hospital unit in Europe. On a lark, he decided to study drawing after returning from war. Following his graduation from the University of Iowa, Stout spent five years in hand-to-mouth jobs, saving for the tour of the cultural centers of Europe that was the unspoken prerequisite of a career in the arts. By the time he arrived at Harvard to begin graduate studies in 1926, Stout was a 28-year-old husband with a pregnant wife and a stipend just large enough to stay “only a little above starvation level.”

In 1928, Stout joined the small art conservation department at the Fogg Art Museum as an unpaid graduate assistant. Conservation, the technical art of preserving older or damaged works, was the least popular field in the art history department, and Stout was probably its most diligent and self-effacing disciple. In fact, in a department based on braggadocio, where a student’s prospects were often based on personal relationships with superstar professors like Paul Sachs, Stout was perhaps the most anonymous student. But he was also meticulous, a trait that carried over to his personal appearance: carefully swept-back hair, trim worsted suits, and a fine pencil mustache. Stout was dapper, debonair, and resolutely unflappable. But beneath his placid exterior was a brilliant and restless mind, capable of great leaps of understanding and far-reaching vision. He also possessed another essential quality: extraordinary patience.

Soon after joining the conservation department, Stout noticed an abandoned card catalogue from the university library. The rows of tiny drawers gave him an idea. The department contained an astonishing array of the raw materials of painting: pigments, stones, dried plants, oils, resins, gums, glues, and balsams. With the help of the department chemist, John Gettens, Stout placed samples in each of the card catalogue’s drawers, added various chemicals, and observed the results. And took notes. And observed. And waited. For years. Five years later, using only piles of scraps and a discarded chest of drawers, Stout and Gettens had pioneered studies in three branches of the science of art conservation: rudiments (understanding raw materials), degradation (understanding the causes of deterioration), and reparations (stopping and then repairing damage).

The breakthrough led Stout—still known only to the handful of practitioners in his field—to a new mission. For centuries, conservation had been considered an art, the domain of restorers trained by masters in the techniques of repainting. If it was going to become a science, as Stout’s experiments suggested, then it needed a body of scientific knowledge. Throughout the 1930s, Stout corresponded regularly with the great conservators of the day, sharing information and slowly compiling a set of scientific principles for the evaluation and preservation of paintings and visual arts.

Things began to change in July 1936, when the Spanish Fascists plunged their country into a civil war. In the spring of 1937, Germany entered the conflict and unleashed, for the first time, its corps of tanks and airplanes, the foundation of its evolving doctrine of “lightning warfare.”

The art world realized that Germany’s powerful weapons, and especially its use of massive aerial bombardment, had suddenly made the bulk of the continent’s great artistic masterpieces susceptible to destruction. The Europeans and British quickly began to develop plans for protection and evacuation, and George Stout began to slowly, letter by letter, reshape his storehouse of knowledge for a world at war. An expert and a precisionist makes his analysis first, he always said, then his decision.

He spent most of 1942 training curators and pushing for a national conservation plan. But by that fall the unflappable Stout was discouraged. He had spent his entire career developing expertise in an obscure subset of art history, and suddenly world events had thrust that expertise to the forefront. This was the moment for art conservation—and nobody would listen to him. Instead, the wartime conservation movement was being controlled by the museum directors, the “sahibs” of the art world, as Stout called them. Stout was a workman, a toiler in the trenches, and he had the nuts-and-bolts technician’s distaste for the manager’s world of committees, conversations, and the cultivation of clients. He was convinced that only his dedicated corps of “special workmen,” trained in art conservation and working through the army, could accomplish anything of lasting value in the coming war.

By January 1943, with the nation at war and in need of men, he had given up on the conservation program and applied for active duty in the navy, in which he had been a reservist since the end of World War I. “In these last months,” he admitted in a letter home after his arrival at Patuxent River Naval Air Station in Maryland, “I have not felt worthy. I was failing to get done what in these times a man ought to do.”

Although he couldn’t tell his wife what he was doing because of the military censors—he was testing camouflage paint for airplanes—he assured her that he was happy. “[The job] has so much to it and so much responsibility that I am scared and pleased. If we can do what we hope to do, or any decent part of it, I’ll have no doubt about what is called ‘making a contribution.’”

Even when his transfer came through in January 1944, Stout remained unconvinced. “…If this were a civilian museum command, I’d ditch. [But] my associates will be military men, as I understand it. In the Army and the Navy, efficiency is the rule and plain honesty holds in relations with people. Bluff does not usually get very far. And so we’ll see.”

Stout underestimated the sahibs. It is doubtful the U.S. Army would have tolerated the MFAA if not for the prestige of the Roberts Commission [the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in Europe, chaired by Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts], which had been formed with Roosevelt’s explicit backing, and no one was better suited to assemble Stout’s corps of “special workmen” than the men who ran America’s cultural establishment. They were able to take the two primary lessons of North Africa and Sicily—that the army would listen to conservation officials, as long as they were military officers, and that those officers needed to arrive at the front lines during or immediately after the fighting, not weeks or even months later—and form from them the basis of a workable plan.

[But] there was no formal mission statement, or even set chain of command. Nobody seemed clear about how many men were needed for the job, how they would be distributed on the continent, even when or if more soldiers would arrive. Men simply showed up for duty with their transfer papers, seemingly at random. A general guidebook to conservation procedures had been culled from Stout’s expertise and writings on the subject. But the Monuments Men had no formal training. Most of the effort was being put into basics like listing the protected monuments in the various countries of Europe. As far as Stout could tell, there was no one even handling the military side of the operation, such as procuring weapons, jeeps, uniforms, or rations. To say the race to put together a conservation unit before the invasion of France had started slowly was an understatement.

Stout was a scientist, a modernizer, but he never put his faith in machines. The skilled observer, not the machine, was the essence of conservation. That was the secret, he believed, to success in any endeavor: to be a careful, knowledgeable, and efficient observer of the world, and to act in accordance with what you saw. To be successful in the field, a Monuments officer would need not just knowledge; he would need passion, smarts, flexibility, an understanding of military culture: the way of the gun, the chain of command.

The military still wasn’t confident this was a good idea. The Monuments Men were only advisors; they couldn’t force any officer, of any rank, to act. They were allowed freedom of movement, but they would have no vehicles, no offices, no support staff, and no backup plan. The army had given them a boat, but not the motor.

By June 1, the MFAA had reached its battle-ready number. Fifteen men would be serving on the continent, excluding Italy: eight Americans and seven Britons. Seven of the men would serve at headquarters in a strictly organizational capacity. The other eight men were assigned to British and American armies…As impossible as it seems, it was the duty of these eight officers to inspect and preserve every important monument the Allied forces encountered between the English Channel and Berlin.

“Stout was a leader,” Craig Hugh Smyth, a later arrival to the Monuments Men, once wrote of him, “quiet, unselfish, modest, yet very strong, very thoughtful and remarkably innovative. Whether speaking or writing, he was economical with words, precise, vivid. One believed what he said; one wanted to do what he proposed.”

One of the first Monuments Men ashore, arriving in Normandy on July 4, Stout sought to identify problems and find ways to solve them.

Not enough “ Off Limits” signs? The army had a printing press in Cherbourg they turned on at night. In the meantime, the rest of the men could make them in the field.

Soldiers and civilians tended to ignore handwritten signs? Stout had the solution for that one, too: use white engineering tape around important locations. No soldier would scavenge in a site clearly marked “DANGER: MINES!”

On May 26, 1944, just 11 days before the invasion of northern Europe, General Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, issued the following order:

Shortly we will be fighting our way across the Continent of Europe in battles designed to preserve our civilization. Inevitably, in the path of our advance will be found historical monuments and cultural centers which symbolize to the world all that we are fighting to preserve.

It is the responsibility of every commander to protect and respect these symbols whenever possible.

In some circumstances the success of the military operation may be prejudiced in our reluctance to destroy these revered objects. Then, as at Cassino, where the enemy relied on our emotional attachments to shield his defense, the lives of our men are paramount. So, where military necessity dictates, commanders may order the required action even though it involves destruction to some honored site.

But there are many circumstances in which damage and destruction are not necessary and cannot be justified. In such cases, through the exercise of restraint and discipline, commanders will preserve centers and objects of historical and cultural significance. Civil Affairs Staffs at higher echelons will advise commanders of the locations of historical monuments of this type, both in advance of the frontlines and in occupied areas. This information, together with the necessary instruction, will be passed down through command channels to all echelons.

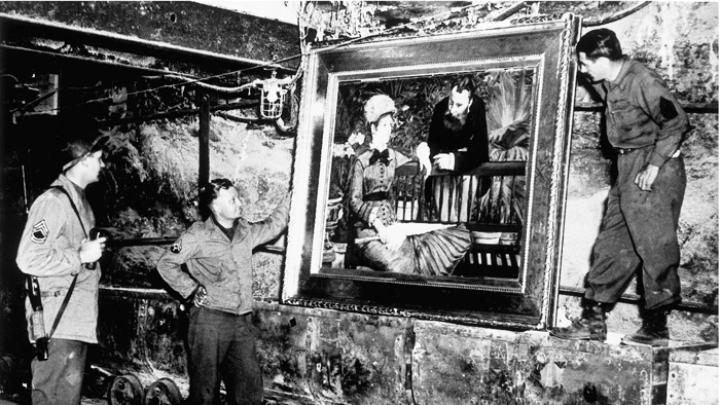

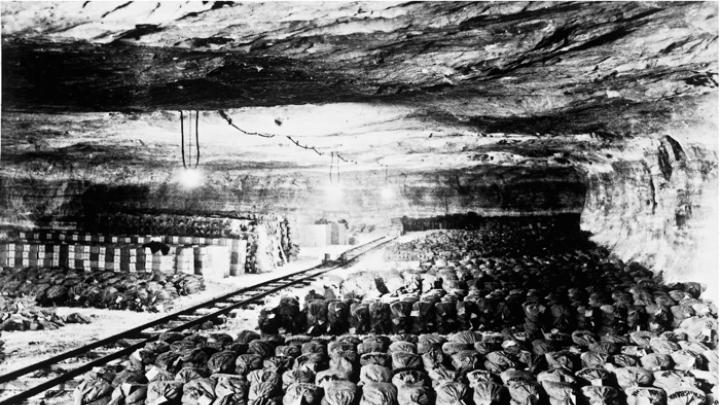

The Monuments Men’s ability to improvise in the field while tracking down, documenting, and protecting works of art faced special challenges once Allied armies entered Germany, where many of the Third Reich’s treasures had been stored deep in mines, sometimes booby-trapped with explosives. On April 6, 1945, U.S. troops took possession of the Merkers mine complex in Thuringia. Robert Posey and Lincoln Kirstein, the Monuments Men serving with the Third Army, arrived two days later.

Slowly, Posey and Kirstein began to realize just how much was hidden in the Merkers mines. Crated sculpture, hastily packed, with photographs clipped from museum catalogues to show what was inside. Ancient Egyptian papyri in metal cases, which the salt in the mine had reduced to the consistency of wet cardboard. There was no time to examine the priceless antiquities inside, for in other rooms there were ancient Greek and Roman decorative works, Byzantine mosaics, Islamic rugs, leather and buckram portfolio boxes. Hidden in an inconspicuous side room, they found the original woodcuts of Albrecht Dürer’s famous Apocalypse series of 1498. And then more crates of paintings—a Rubens, a Goya, a Cranach packed together with minor works.

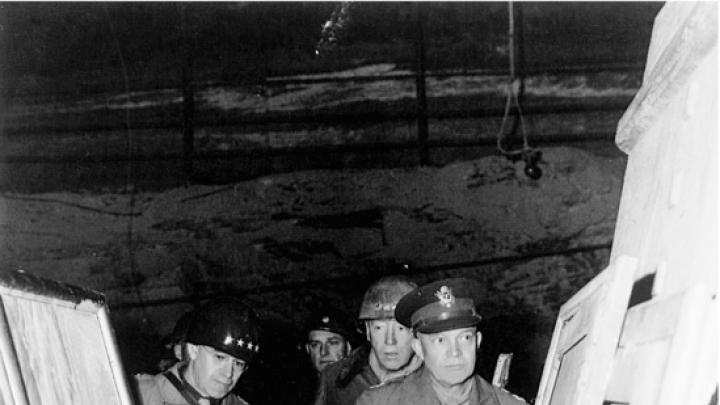

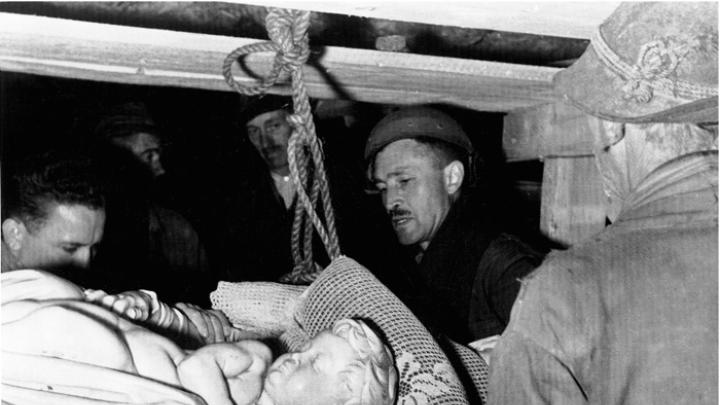

George Stout arrived at Merkers on April 11, 1945. It was crawling with Western Allied officers, German guides, and experts from all branches of Civil Affairs. As Kirstein wrote, “Due to the fact that the works of art…were discovered as an adjunct to the uncovering of the Reich’s gold-reserve, the story was given unusual press treatment.”

The next morning, Stout met Dr. Paul Ortwin Rave, a German art expert who had been living on the premises since April 3. A dedicated and professional museum man, his career had been stymied by his refusal to join the Nazi Party. In 1943, Rave suggested evacuating collections from the Berlin area, which was beginning to come under Allied aerial bombardment. He was told this was dangerously defeatist thinking…perhaps fatally so. Nonetheless, he tried again the next year; he was again dismissed, and his life once again threatened. It wasn’t until Soviet long-range ground artillery started battering the city that authorization was obtained to remove the artwork to Merkers. Rave estimated it would take eight weeks to move; he was given two. The final shipment arrived on March 31. Five days later, the U.S. Third Army overran the area.

“Two weeks to move this massive amount of art,” Stout commented at the end of Rave’s tale. “What a luxury. We’ve been given six days.”

Going into a potassium mine—or a copper mine, or a salt mine, or any other type of German mine—was an uncomfortable experience. These were working mines, not tourist sites, and the passageways were rough, narrow, and cramped. Much of the equipment was old and, because the war had drawn away men and materials, poorly maintained. The Germans had chosen the safety of deep mines for their repositories, so the soldiers often traveled a quarter-mile into the ground, and another quarter-mile laterally at the bottom. To exist in perpetual darkness, far below the earth, without a map of the mine or assurance the next passageway wasn’t booby-trapped or the next holding bay not full of dynamite, was a nerve-jangling experience. Even worse, most of the mines were in areas that had been bombed or shelled, knocking out their power supplies. They were dark, cold, and damp.

The Merkers complex included more than 35 miles of tunnels and a dozen entrances. There was no inventory of the works in the mines, but Dr. Rave had a list of the museums and collections from which they had come.

On the morning of April 13, Stout worked out the materials needed to pack all the artwork for shipment: boxes, crates, files, tape, thousands of feet of packing materials. His conclusion: “No chance of getting them.”

In addition, Stout learned that instead of evacuating on April 17, they would be leaving on April 15. “A rash procedure,” Stout noted in his diary, “and ascribed to military necessity.” General Patton was charging ahead, and he didn’t want to leave four battalions behind to guard a gold mine. Furthermore, Merkers, and all its treasures, were in the Russian zone of occupation.

Thirty minutes after midnight on April 15, Stout finished his plans for the evacuation of Merkers. Unable to secure packing materials, he had requisitioned from the Luftwaffe uniform depot Kirstein found in the Menzengraben mine a thousand sheepskin coats, the kind German officers used on the Russian front. Most of the 40 tons of artwork would be wrapped in the coats, recrated with similar works, then organized into appropriate collections. … The gold was too heavy to be loaded to the tops of the trucks, so crates of paintings would be mixed in to maximize the load. Loading would start in an hour, at 0200, 36 hours ahead of the original schedule. By 0430 the artwork already in crates or boxes was brought to the surface and loaded. “No time to sleep,” Stout wrote. He had to prepare invoices and detailed instructions for the unloading and storage of the artwork in Frankfurt.

At 0800, an hour before the first convoy left, Stout started on the uncrated paintings. He planned to move them to a building above ground for temporary storage, but even with 25 men, the work proved impossible. By noon, the crew had reached 50, and Stout had decided to crate the paintings underground. Unfortunately, the large crates were awkward to handle, especially in the confusion of the mineshafts. Jeeps had been brought down to help transport the gold, blocking some passages. Their exhaust fouled the air, and the occasional backfire of an engine echoed ominously in the rocky corridors. The gold was being sprayed with water to remove the corrosive salt of the mine, and the main shaft to the elevator was ankle-deep with the runoff. Soldiers were scurrying in all directions, carrying stacks of money, bags of gold, and ancient art, and it was all Stout could do to keep his men from wandering off in the confusion and not returning to work.

At 0005, five minutes past midnight on April 16, Stout reported “all paintings on ground level, in 3 places. All print boxes on ground level in 2 places. Cased works below ground somewhat rearranged and piled in part ready to load at elevator shaft.” The loading at Ransbach started at 0830; the loading at Merkers a half hour later with 75 men and five officers. At 1300, prisoners of war were brought in to assist the operation. By 2100 all the paintings were loaded. Stout went to the Dietlas mine, reached by an underground passage from the main shaft at Merkers, and found photographic equipment, modern paintings, and racks of archives. One set from Weimar was marked 933–1931, a thousand years of municipal history. “Inspection finished 2300,” he wrote.“Returned Merkers, ate supper, reported.”

The art convoy—32 10-ton trucks with a motorized infantry escort and air cover—left for Frankfurt at 0830. It arrived at 1400. Stout noted only “complicated unloading. L. Kirstein a great help. All handled by 105 PWs [prisoners of war] in poor health. Storage in temporary arrangement 8 rooms basement level, one large room underground.” Stout’s inventory listed 393 paintings (uncrated), 2,091 print boxes, 1,214 cases, and 140 textiles, representing most of the Prussian state art collection. “Job finished and area secured 2330.”

“The last time I saw them,” Lincoln Kirstein wrote in his account of the operation, “Lieutenant Stout was gravely whirling a swing aerometer in all corners of their new home, determining the humidity.” He had been up for almost four straight days, but as always with Stout the job got done—and done right.

It had been a remarkable few weeks, but no Monuments Men were celebrating. If the Western Allied forces could stumble on Merkers, they could easily stumble on something just as extraordinary and unexpected…. And still out there, somewhere in Nazi hands, were known to be two great treasure troves of looted European art: the cream of the French artistic patrimony, reportedly stored in the castle at Neuschwanstein; and Hitler’s treasure chamber deep at Altaussee, in the Austrian Alps, which contained many of the greatest works of art in the world.

When George Stout left Europe in August 1945 after little more than 13 months, he had discovered, analyzed, and packed tens of thousands of pieces of artwork, including 80 truckloads from Altaussee alone. He had organized the MFAA field officers at Normandy, pushed command headquarters to expand and support the monuments effort, mentored the other Monuments Men across France and Germany, interrogated many of the important Nazi art officials, and inspected most of the Nazi repositories south of Berlin and east of the Rhine. It would be no exaggeration to guess he put 50,000 miles on his old captured VW and visited nearly every area of action in U.S. Twelfth Army Group territory. And during his entire tour of duty on the continent, he had taken exactly one and a half days off.

He then requested and received a transfer to the Pacific theater, arriving in Japan in October and serving as chief of the Arts and Monuments Division at Headquarters of the Supreme Command for the Allied Powers, Tokyo, until mid 1946. For his years of service, Stout received the Bronze Star and Army Commendation Medal.

After his tour in Japan, Stout returned briefly to Harvard’s Fogg Museum. In 1947, he became director of the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts, where he served until becoming director of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.

By the time he retired in 1970, he was considered one of the giants in the field of art conservation.

His service in World War II, meanwhile, remained almost completely unknown. One major reason was that Stout rarely discussed it.

Those who knew him, though, were unequivocal about the significance of his contribution to the MFAA and the preservation of European culture.…Lincoln Kirstein put it best because he put it most bluntly. “[George Stout] was the greatest war hero of all time—he actually saved all the art that everybody else talked about.”

Nonetheless, it is not surprising that George Stout’s contribution to the MFAA was never truly appreciated because, in the decades following the war, the MFAA section and its work was itself lost in the fog of history. Part of this was circumstance. The Monuments Men were typical of “the Greatest Generation” and tended to downplay their roles in the war. Since they did not serve as a unit, there was no official history.

Perhaps because of this, the army essentially forgot about the monuments conservation effort. There was no dedicated unit equivalent to the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives section in the Korean War, and there hasn’t been one in any war since.