In 1968, Stephen Bergman ’66, M.D. ’73, was driving through the desert in Morocco on a dead-straight road. At one point, he noticed the sun going down directly in front of him while the moon was rising behind. “I had never seen anything like that on Earth,” he recalls.

The sunset/moonrise moment seemed an epiphany, “a sign,” he says, that the symmetries and mysteries of the world, which art echoes, were, for him, life at its richest. Somehow it seemed to validate his innate wish to be a writer, although at that time, Bergman’s actual writing “was too precious to show anyone,” he says. Still, “an adventure had shown itself to me. I loved feeling free of all these damn schools I had spent my life in.”

Even so, Bergman scarcely imagined himself becoming one of the world’s most widely read authors. A decade hence, his first novel, The House of God, on his internship at a Boston hospital, appeared under the pen name “Samuel Shem.” Over time it built a vast global readership that continues even today, with more than 2 million copies sold and translations available in all the world’s major languages. “It’s a brilliant satire of medical education, the Catch-22 of medicine,” says Peter M. Brigham ’70, M.D., a retired psychiatrist in Cambridge. “Given the awful things that can happen when you go through an internship, it shows the pitfalls of closing off, and the need to stay with your human reactions of disgust, pain, and empathy. And it’s just so funny!”

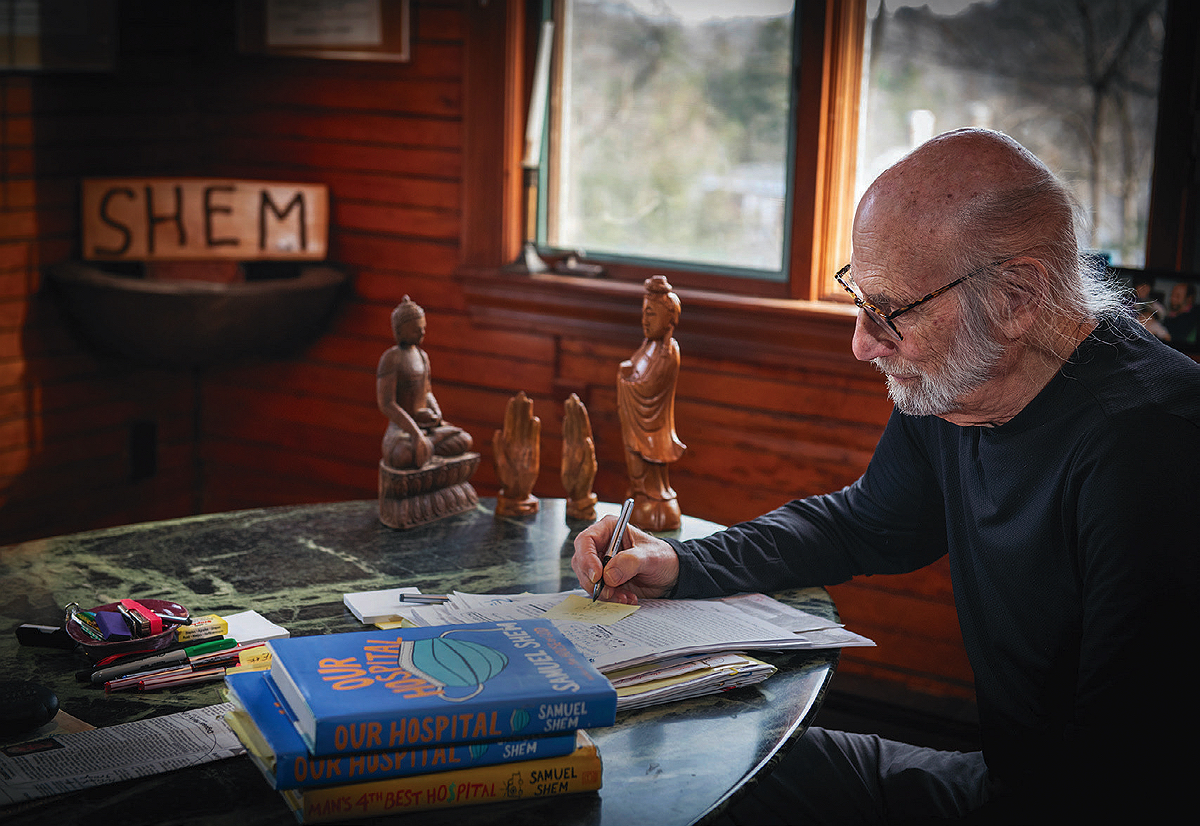

The House of God became the flagship of Bergman’s “healing quartet,” embracing three more novels that follow protagonist Roy Basch, M.D., and his fellow interns into their later careers. The series culminates in the 2023 finale, Our Hospital, wrapping up his risible, skeptical, and grittily realistic medical saga with a harrowing account of the same cast struggling with the COVID-19 pandemic at a small-town hospital in upstate New York.

Back in 1968, Bergman was writing only for himself, in his third year as a Rhodes Scholar at Balliol College, Oxford, he says now, from his home in Newton, Massachusetts. Enrolled in a doctoral program and studying the neurophysiology of memory, he ran daily experiments teaching cockroaches to lift their legs. But he was also writing in earnest: plays, poems, short stories, and a diary. To move to England, Bergman had broken off with his college girlfriend (now wife) Janet Surrey, and was also reading voluminously, seeing friends, and living in a rented house in the Cotswolds.

At Harvard, Bergman had fulfilled his premedical requirements but had always felt like a writer, not a doctor. After his momentous Morocco sojourn, he shared the revelation he’d had with his academic adviser, the eminent British cardiac physiologist Denis Noble. Without missing a beat, the scientist said, “Well, then, have a sherry.” They sat down to mull over careers and callings in a conversation that has never ended; even now, the two men talk frequently via Zoom.

Bergman’s literary passions had a pedigree. In high school and college, he took summer jobs as a toll collector on the Rip Van Winkle Bridge, which crosses the Hudson River near his childhood home of Hudson, New York. To enable reading on the job, he asked for the somnolent midnight-to-dawn shift, which let him devour the towering Russian novels and plays by Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Turgenev, and Chekhov.

Unfortunately, at Harvard, a bucket of cold water awaited his writing ambitions. The note “See me” appeared without elaboration on his first essay in freshman composition, and Bergman fantasized that his section leader must have wanted to tell him in person how great it was. Instead, she informed the boy that his paper deserved a grade “below F.” A revised version fetched, “Terrific! D-.” So Bergman turned his attention to playing for the varsity golf team and researching the neurology of memory via surgery on cat brains. “I didn’t dare write anything else at Harvard,” he says. Even so, in addition to meeting Janet, a Tufts undergraduate, he acquitted himself well enough academically to earn a Rhodes Scholarship.

Post-Rhodes, the budding writer won acceptance at Harvard Medical School. With the Vietnam War raging, his actual career ambitions became somewhat irrelevant, since enrolling in medical school would grant him a draft deferment. Essentially, his draft board made him choose between Harvard and Vietnam. “I chose Harvard,” he wrote decades later, in a biographical essay on writing. “I realized that if I depended on my writing for my livelihood, I wouldn’t be able to write what I wanted—I’d probably wind up in television or film. Medicine would be my meal ticket. Somehow, I would find a way to write. I am a writer who happened to be trained as a doctor.”

Having returned to the States, Bergman settled in Boston again and reunited with Janet. He enrolled at Harvard and settled into a physician’s career path. At that time, after four years of courses and rotations, medical students still had to serve a hospital internship to complete their M.D.s. Bergman was already interested in psychiatry and could have gone directly into a psychiatry residency, bypassing a regular internship. “But I needed to know what it’s like taking care of people—real doctoring,” he recalls. He had an excellent med-school transcript along with a D.Phil. from Oxford, and got an “A” rating in the national “lottery” that matches students with hospitals for their internships.

His first choice was Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), by any standard one of the nation’s most prestigious hospitals (and nicknamed “Man’s Greatest Hospital” in Bergman’s fiction and elsewhere). He considered himself a “lock” for MGH, so was stunned when the process matched him with a different Harvard teaching hospital, Beth Israel (then known as BI, now the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center), in Harvard’s Longwood Medical Area, where he served his internship.

Years later, Bergman chanced to talk with an MGH physician and confessed his bewilderment as to why Mass General passed on him. It turned out that internship interviews he had done with several doctors nixed his chances. “You said, ‘I am writing plays,’” the MGH doctor explained. “When you started talking about writing plays, you lit up! We thought, ‘He’s not going to stay here.’”

No doubt it was a fortuitous turn of events; as Bergman explains, “If I had gone to MGH, I never would have gotten a sense of what happened at BI. And BI was the number-one choice of med students nationally. We had top-notch doctors there—we did everything right.” What ensued was the tumultuous, outrageous, infuriating, hilarious, raunchy, and disillusioning year portrayed in The House of God, the 1978 novel by “Samuel Shem,” a nom de plume he’s retained for his 10 subsequent books.

Bergman did not sit down to write a novel. It grew from something more like a memoir. The colorful interns and residents who populate The House of God are mostly based on real people.

In the mid-1970s, Bergman moved into an attic in Newton and began a psychiatry residency at McLean Hospital, the Harvard-affiliated psychiatric facility in Belmont, Massachusetts. The BI interns had become close friends; Bergman eventually gave them fictional monikers like Eat My Dust Eddie, Hyper Hooper, and The Runt. The newly minted M.D.s began convening at Bergman’s attic pad to drink, get high, and process their mind-blowing year in the hospital. “We’d start telling jokes about what it was like,” he fondly remembers. “It was the most fun I’ve ever had. The anger and resentment over how we were treated kept boiling over—it was catharsis, and sheer fun! I taped a lot of the sessions; they were so compelling. Transcribing the tapes on my IBM Selectric was very funny.” He accumulated three or four chapters’ worth of material, laughing out loud as he typed but never imagining it in book form: “I never wanted to write a novel. I was a playwright.”

He’d been seeking a literary agent for his plays, and one of them asked to see the funny notes on his medical internship. When they next talked, she began with, “You’re either a madman or a genius, but I really love what you write.”

The book frames “13 Laws of the House of God,” most introduced sequentially in ALL CAPS ....The Third Law, for example, is,“At a cardiac arrest, the first procedure is to take your own pulse.”

“I can’t help you on that,” Bergman replied, “but at the moment, I am standing in a major mental hospital.”

The agent got his material to Joyce Adelson, an editor at Putnam who “taught me how to write a novel,” he says. For the next couple of years, the young physician worked steadily on the manuscript. Fortunately, he found his psychiatry training at McLean undemanding; he could spend mornings at home writing and only appear at the hospital in the afternoons. He revised the text seven times, and “by the end” he says, “I could recite it,”

The House of God is a kind of bildungsroman cast as a black comedy. Narrator Roy Basch, Bergman’s alter ego, is, despite his medical education at the “BMS,” or “Best Medical School,” woefully unprepared for confronting real patients who are suffering, or at least think they are. The chaos of hospital life—where odd syndromes, irrational rules, and avoidable and unavoidable fatalities disrupt the interns’ lives—inflicts ongoing trauma. Grueling hours debilitate doctors, who often feel like they’ve been thrown into the deep end of a pool with no swimming lessons—and no lifeguard.

Basch finds a mentor, a second-year resident known only as The Fat Man, an imaginary character and another of Bergman’s alter egos. The Fat Man is savvy, caring, and resolutely pragmatic, helping his interns find ways to survive and stay sane amid the relentless physical, emotional, and mental challenges. His tactics typically involve breaking or circumventing medical conventions.

Famously, the book frames “13 Laws of the House of God,” most of them formulated by The Fat Man and introduced sequentially in ALL CAPS as the story unfolds. The Third Law, for example, is, “At a cardiac arrest, the first procedure is to take your own pulse.” With surprise and disenchantment, Basch discovers that one major source of trouble for both doctors and patients is unneeded or even harmful medical treatment. He learns to satisfy bossy, hidebound supervisors by claiming to have performed numerous tests and treatments on elderly, infirm patients nicknamed GOMERS (for Get Out of My Emergency Room) but actually foregoing treatment—with salutary results that only enhance Basch’s standing among the staff. Such outcomes support the thirteenth and final Law, devised by Basch himself: “The delivery of medical care is to do as much nothing as possible.”

Hospitals are rife with wrenching moments that naïve interns are rarely equipped to handle. In his later essay, Bergman recalled his own experience as an intern asked to deliver bad news to a dying patient, one of the most difficult moments in any doctor’s life. There was a BI patient with metastatic breast cancer. In the operating room, surgeons realized that treatment was hopeless and so closed up her body without surgical intervention. Bergman recalls begging off from the painful task of informing the patient, telling his resident that it was a job for her private doctor or the surgeon. In the real world of 1974, a nurse eventually broke the bad news. But in the novel, The Fat Man volunteers for the duty as Basch watches from the doorway:

I watched him enter her room and sit on the bed. The woman was forty. Thin and pale, she blended with the sheets. I pictured her spine X-rays: riddled with cancer, a honeycomb of bone. If she moved too suddenly, she’d crack a vertebra, sever her spinal cord, paralyze herself. Her neck brace made her look more stoic than she was. In the midst of her waxy face, her eyes seemed immense. From the corridor I watched her ask Fats her question, and then search him for his answer. When he spoke, her eyes pooled with tears. I saw the Fat Man’s hand reach out and, motherly, envelop hers. I couldn’t watch. Despairing, I went to bed.

Later that night, Roy peeks into the room again. “Fats was still there, playing cards, chatting. As I passed, something surprising happened in the game, a shout bubbled up, and both the players burst out laughing.”

Bergman chose the pseudonym Samuel Shem because, he says, “I wanted my life to be what it was, and I didn’t want to be running around talking about my book. I thought it would be harder to keep writing if I had people writing about me and talking about me. For two years, I didn’t do anything at all to promote the book.” Nor did he want his psychiatric patients to know that he was Samuel Shem.

In the marketplace, The House of God began with bad luck: about three weeks after its publication date, New York newspapers went on strike. Putnam’s first printing of 10,000 copies had “a miserable start,” the author says. But word of mouth has formidable power. The book spread like wildfire through the medical and healthcare community; eventually it seemed that virtually every young doctor and nurse had read it, almost as a rite of passage. Bookstores everywhere sold out.

Many doctors “hate to treat alcoholics,” Bergman says. “But I liked working with them. When they get sober, they get better.”

A couple of years after publication, Bergman was sitting in his backyard opening a letter forwarded from Putnam. It came from an intern in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “I am on call alone all night at a veterans’ hospital here,” it said. “If I didn’t have your book, I’d kill myself.”

“I got a shiver down my spine,” Bergman recalls. “It was like, ‘Oh—this is that important? OK, I’m a doctor, I’ll go out and help.’ From that point on, I never turned down an offer to speak, anywhere. I didn’t care about the money, I just never said no.” He has addressed scores of medical school commencements, all over North America and Europe, and a few times in Australia. “I really talk about the same thing everywhere: staying human in medicine,” he explains, “the danger of isolation, and the healing power of good connection, which means a mutual one.”

There was controversy, of course: “Medical people my age and younger ate it up, but the older guys hated it,” Bergman says. Letter-writing battles erupted in the pages of The New England Journal of Medicine. Though House of God never caught on with the literati or became a mainstream bestseller, after decades in print, its enormous readership has settled the verdict. In 2016, Publishers Weekly placed it second on its list of the 10 greatest satires of all time, behind only Don Quixote and just above Catch-22 . It continues to sell vigorously anywhere there are doctors, nurses, patients, and hospitals. Amazingly, after 45 years, the book’s royalties remain as robust as ever. “I still hear about it every day,” Bergman says.

In 1984, Paramount produced an eponymous feature film, with Tim Matheson (later of The West Wing) playing Roy Basch. It was never released, and Bergman calls it a “fiasco, not funny and not edgy,” but happily, the sale of movie rights enabled him and Janet to buy a large home in Newton with a capacious carriage house in back, where Bergman has his office.

Bergman remained at McLean, practicing psychiatry until 2005 and serving nearly as long as an instructor in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. His career has placed him either at a writing desk or in a hospital. “I liked psychiatry,” he says. “You learn about people. I saw everything in terms of what would help me be a writer.” Having seen patients die at Beth Israel, he also welcomed the fact that, unlike most medical specialties, other than suicides, “Nobody dies in psychiatry.”

At one point, a psychiatrist Bergman had supervised came to direct a rehab center for alcoholics and drug addicts. “They needed therapists, and he sent them to me,” Bergman says. “A lot of doctors hate to treat alcoholics—after putting in so much work with them, they go out and get drunk again. But I liked working with them. When they get sober, they actually get better, dramatically better.”

Janet, a psychotherapist and Buddhist meditation teacher, shared a second home with Bergman in Gloucester, Massachusetts. (The couple have also raised an adopted daughter, Katie Surrey, a scientist specializing in animal habitats.) Janet knew about Alcoholics Anonymous and was sending her patients to a Gloucester AA meeting. She took Bergman to one, an experience that “opened my eyes to my own self and alcohol—‘Maybe I’m an alcoholic.’” At Oxford, he remembered, pretty much everyone drank a good deal every day, himself included.

“I could have been dead,” he says, and gives a chilling example. One Sunday morning, he got onto his big BMW motorcycle, barefoot and without a helmet, clad in only a pair of shorts and determined to hit “a ton”—motorcyclist slang for 100 MPH. On a two-lane road, flying downhill, he did reach 100, shooting the gap between oncoming cars and ones in his lane. Luckily, he coasted up the next hill unharmed.

Bergman began going to AA in Gloucester and seeing alcoholic patients, requiring them to attend AA meetings as a condition of therapy. “Everybody got better!” he exults. Inspired, Bergman returned to his playwriting roots and collaborated with Surrey on Bill W. and Dr. Bob, a play about the alcoholic businessman and physician who founded Alcoholics Anonymous in 1935. The couple painstakingly researched the play, not only reading source material but interviewing living friends of the two men, and Dr. Bob’s daughter.

First produced off-Broadway in 2007, the play ran in New York for 132 performances and has had two more off-Broadway productions as well as stagings in 30 U.S. states and Australia, Canada, and Great Britain. Bergman calls it one of his “proudest accomplishments,” citing how the AA model, which brings together biological, psychological, spiritual, and community factors, is so widely applicable and effective. And after all, he notes, “Everywhere you go, there are drunks.”

“Janet has been incredibly important for me,” Bergman says. Surrey’s work in relational-cultural theory, for example, showed her husband a new way of viewing health: not as a state attained by a separate, disconnected “self,” but as a relational entity in connection with others, be they humans, animals, or plants in the natural world. “She and I joined hands and went all over the world to share this relational perspective on health and life,” he says.

The core of his work for decades now, both with Surrey and on his own, involves bringing the relational sensibility to healthcare professionals. A 1984 talk he gave at the Stone Center for Women at Wellesley College summarizes the mission: “Staying Human in Medicine: The Danger of Isolation and the Healing Power of Good Connection.”

That’s also a fair summary of Bergman’s teaching at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, where he has been a clinical professor in the departments of both medicine and psychiatry since 2014. Over the years, he’d done presentations at NYU but was surprised when Dean Robert Grossman phoned to offer him a position. “We want you to teach The House of God!” the dean explained. Teaching in the humanities wing of the medical school, Bergman has offered six-week seminars on the patient-care issues dramatized in The House of God and his subsequent healing-oriented novels.

As always, he emphasizes that “connection comes first. We are all in this together! If, as a doctor, you’re not connected, you won’t hear the patient’s story, which is how you build mutual trust.” He adds that the quality of relationship is what underlies patients’ compliance with medical advice: “If you are mutually connected, the patient will listen to you. If you aren’t connected, the patient will not listen.”

Eventually, Bergman fictionalized his early years at McLean into Mount Misery, the second novel of his “healing quartet,” this one on psychiatric training and published in 1997. (The novel renames McLean as Mount Misery.) His last two novels round out the group, returning to Roy Basch and his intern friends from The House of God. In Man’s 4th Best Hospital (2019), the Fat Man leads a “Future of Medicine” clinic at the hospital whose ratings have slipped to only fourth best. Fats convenes some of his old BI gang and they try to resist the ways in which technology and money are displacing the human element from patient care.

“The problems are very simple: money and screens,” Bergman explains. “House staffs now spend 80 percent of their time on computer screens, billing as much as possible for services. The patient is lucky to get eye contact with the doctor, who is sitting at the computer screen seething because he’s tending to a screen instead of doing what he’s supposed to do: paying attention to the patient. Instead of treating the patient, you end up treating the screen.”

The last movement of the quartet, Our Hospital, reunites the same group one last time. Roy Basch has been called back to his hometown of Columbia in upstate New York (modeled on Hudson, where Bergman grew up) to help a small hospital cope with the raging COVID pandemic. He recruits pals like Hyper Hooper and Eat My Dust Eddie to join him (Eat My Dust, for example, had become bored in his California retirement).

Both COVID and the modern healthcare juggernaut have Columbia under stress. One of the town’s older doctors, Orville Rose, who “never put a computer between himself and his patient,” gets forced to sign a 34-page contract with Kush Kare, the for-profit private equity firm that acquired the small local hospital, Whale City Memorial, for its chain. Basch’s group of experienced doctors joins forces with local medical staff to cope with the pandemic. Protagonist Amy Rose, M.D., Orville’s adopted daughter, directs the hospital’s COVID response with energy, intelligence, experience, and compassion. Even Basch becomes her patient, symbolically passing the torch to a younger generation of smart, savvy—and in this case, female—physicians. In fact, in Our Hospital, women professionals like Amy and nurse Leatrice Shumpsky, aka “Shump,” a “smart, tough young grandmother,” lead the battle against both the virus and the commercialization of healthcare. “Finally, I was able to have doctors join nurses to make sure that patient care stays humane,” Bergman says. “And the nurses emerge as the heroines of the story.”

Amy’s dad, Orville Rose, starred in an earlier novel by Bergman/Shem, The Spirit of the Place (2008), which the author considers his best book and which received two national “best novel” awards in literary fiction. Like Our Hospital, it’s a story of homecoming to Bergman’s roots—the same small town of Columbia, New York, this time set in 1983. Immersed in a passionate love affair with an enchanting yoga teacher in Italy, Dr. Rose gets called home by news of his mother’s death. Her unorthodox will bequeaths Orville a million dollars, a fancy Chrysler, and the family house—on condition that he live in the house for at least one year and 13 days. At first nonplussed by this curveball, he decides to stay, working with a town doctor and eventually falling in love with a local historian. As the story unfolds, Orville comes to terms with his late mother as well as the charms and flaws of his hometown. At the end, he must decide to either stay there or take his inheritance and flee.

The novels of homecoming characterize Columbia as a “town of breakage.” The Spirit of the Place notes early on that “School microphones would consistently give out just after someone said, ‘Testing, testing.’ On Memorial Days in Columbia cemeteries, just as the Gettysburg [Address recitation] began, viewing stands would collapse.” In Bergman’s oeuvre, a setting where things are constantly breaking down actually seems ideal for his talents. What is illness, really, but a breakdown of body or mind? Yet broken people, or broken systems, offer a chance to accept and forgive, and also to diagnose and heal. In his fictional worlds of suffering and distress, Bergman the doctor, psychiatrist, and writer has placed himself exactly where he can do the most good.