On an early August day in 1973, as political upheaval was tearing apart Chile, Peter Carter, coach of the Harvard Ski Team, found himself with an automatic pistol held hard against his forehead.

Long seconds ticked by as an irate Chilean soldier debated whether to pull the trigger.

Obviously, he did not because Harvard recently feted the 76-year-old grandfather of seven at a dinner celebrating a $2-million alpine ski coaching endowment created in his name. The Chilean incident is a simple reminder that skiing for Harvard in those days could have surprises.

In post-dinner remarks, Carter, a retired Vermont attorney, acknowledged the extraordinary help of Charles Hirschler ’76, Eric Horsley ’94, Eric O’Brien ’94, and Perry Robinson ’89, prime players behind the endowment’s creation and former members of Harvard ski teams.

Carter then touched on a few stories from an era when skiing for Harvard was underfunded, understaffed, unpredictable, irreverent—and fun. As a plodding member of the team in the late ’60s, I was party to the spirit of this era.

Five days a week the team travelled north (as it still does) from the flatlands of Cambridge to practice and then compete on the Winter Carnival ski circuit. Harvard provided no vehicle. So, Carter purchased “Moby,” a cream-colored Ford station wagon that had been in an eight-car pileup. Moby still had three working doors and an engine. Carter bought the car for one dollar. When crammed with skiers and equipment on snowy New England roads, Moby appeared less to roll than to glide—like an overloaded lifeboat.

“In those years, we got laughed at because of the lack of University support,” noted Carter, who was the nationally ranked ski captain in 1969, and then coached from 1971 to 1975. His expertise was in slalom, a discipline he took seriously—with exceptions. For example, in an era when streaking was commonplace, Carter competed in one race at Pats Peak butt naked. And won.

Outfitting the team was always a financial challenge. One season, thanks to a corporate donation, Carter was able to dress his team in new uniforms. The parkas were bright purple, the pants a two-tone purple and blue with bright yellow zippers. Not a stitch of crimson—but the price was right. The sight led one old-time lift operator at Cannon Mountain to comment: “I reckon people who wear clothing like that usually sit down to pee.”

The Division One Winter Carnival ski circuit then and now includes the best collegiate competitors in the northeast. Until the 1970s, the field was all men, which turned out to be an issue for Sue Cochran ’73, the new manager for the team in 1971.

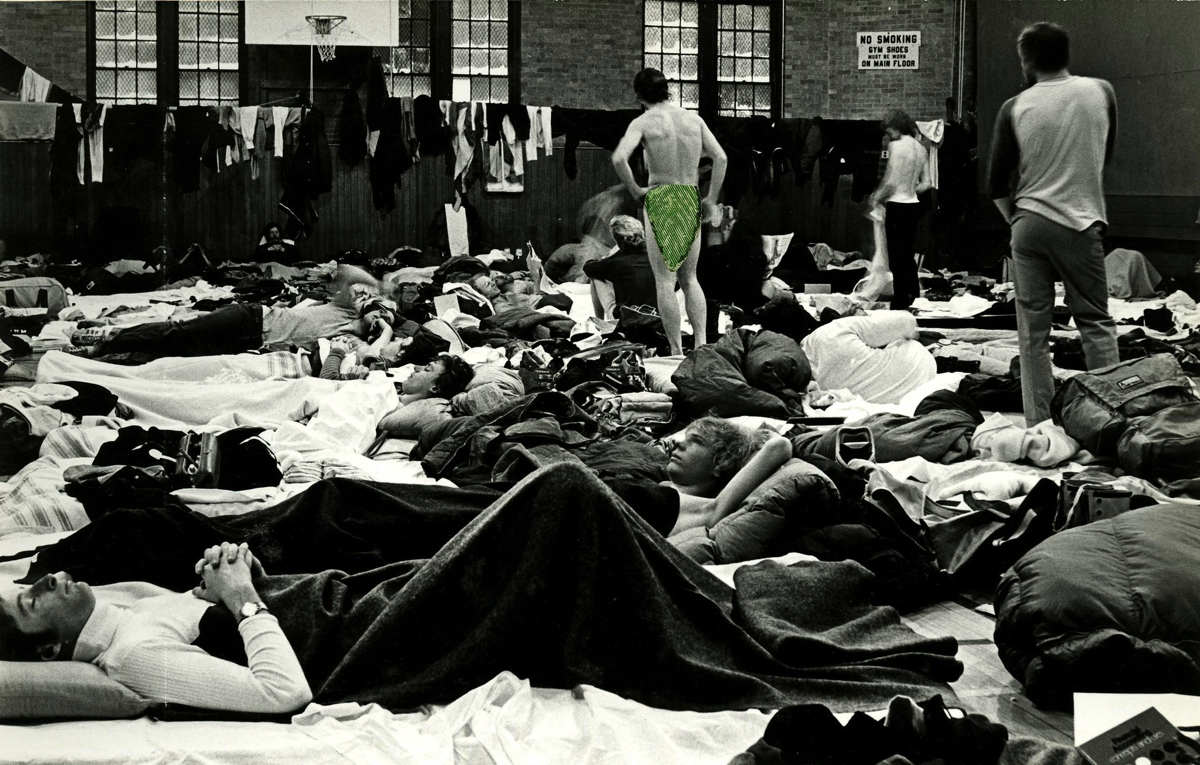

“How could I resist joining an organization that had so much fun, worked so hard, and was just a little bit crazy?” recalled Cochran, who later became a family physician in Skowhegan, Maine. Being a woman in an entirely male environment posed challenges, particularly during overnights at carnivals where everyone slept together on mattresses laid out on the gym floors. A lack of funds and nothing more led Cochran, disguised by teammates, to claim a mattress at Dartmouth. She was discovered. Surprisingly, the scantily clad men of Dartmouth took offense.

So, at the Williams carnival the next week Cochran simply improved her disguise.

Winter Carnivals required participation in four events: slalom, giant slalom, cross country, and the beast of them all, ski jumping. Harvard occasionally, surprisingly, had good jumpers, and one year qualified for the NCAAs because of the team’s jumping prowess. But, far more often, Harvard had to send novices catapulting 200 feet through the air to keep the team qualified.

“It was a bit nerve-wracking. I had to send them off like cannon fodder,” Carter recalled. It was not a confidence-builder that, after 1970, afficionados of ski jumping the world over knew Mr. “Agony of Defeat,” a Slovenian named Vinko Bogataj. His spectacular fall on the approach to the jump takeoff made millions of viewers cringe while watching the television introduction to ABC’s Wide World of Sports. Vinko survived the fall, yet was proof of how badly things could go on a ski jump before you even reached the takeoff lip.

Broughton “Brot” Coburn ’73, today a Wyoming resident and author of several mountaineering books, was one of those nervous Harvard novices. “Some of the recruited Norwegians were so good that they often out-jumped the hill. So, officials had to cut back the takeoff lip. This meant I sometimes couldn’t even clear the knoll [on which the jump was built] to reach the landing hill,” Coburn recalled.

Liability concerns and the rampant recruitment of foreign expert jumpers eventually eliminated jumping at Carnivals.

One preseason, expense-free way that Carter conditioned the team members was to have them run down the entirety of Mount Washington daily. Prior to such a workout (and many other upcountry events), everyone slept over at “Harvard North,” the Carter family vacation home in nearby Jefferson. The runs started with free lifts on the Cog Railway. They were free for a reason.

Carter had worked summers as a brakeman on the Cog. Late one autumn day in 1967 he was aboard when human error led the train, packed with tourists, to start plummeting out of control down from the summit.

When the train eventually flew off the track, eight passengers died and another 70 were injured. Carter survived relatively unscathed to spend the waning daylight assisting the injured. Partly because he kept his composure amidst the tragedy, Carter subsequently won the owner’s gift of free rides for years to come.

That composure was more elusive on September 10, 1973, in Chile. At personal expense, some members of the Harvard team had just finished summer training and racing in Portillo when an American-supported coup d’etat suddenly plunged Chile into violence.

Carter and his charges were in Santiago at the airport preparing to catch the last flight out of the country (the next day President Salvador Allende was assassinated). At the gate, a soldier questioned Carter about some expense records. Irritated, Carter responded in Spanish with attitude. A moment later the soldier had a gun at his head. To this day, Carter figures his chances of living the next two seconds were 70/30.

With the exception of that kerfuffle, Carter said he looks back on his ski team tenure as one might recall life in an extended family. “The friendships, the fun, the incredible comradery,” he added, “those were my biggest rewards.’’