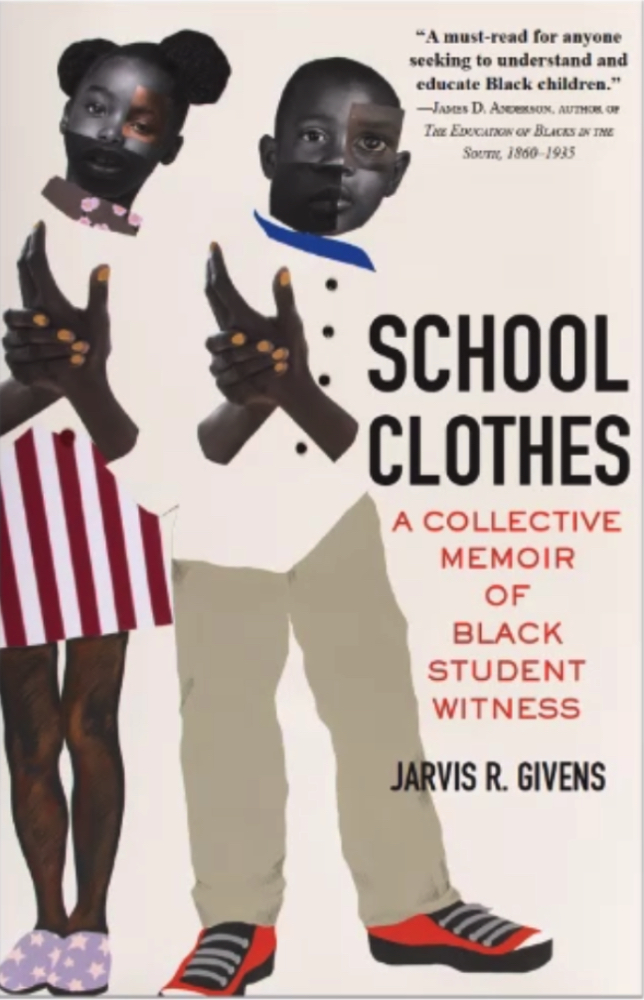

“Black students were always watching,” historian Jarvis Givens told listeners Tuesday evening during an online discussion of his newest book, School Clothes: A Collective Memoir of Black Student Witness. A professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, Givens studies African American history in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, focusing especially on race and power in education. His 2021 book, Fugitive Pedagogy, told the stories of black teachers, from slavery through the Jim Crow era, whose classroom instruction often had to be given covertly, in violation of the law or under threat of violence. That book, Givens said Tuesday, was intended to correct “a historical narrative that for so long presented these educators as passive political actors.”

The new volume picks up where Fugitive Pedagogy left off: with the students those teachers taught. Drawing on a range of archival materials to weave together more than 100 narratives of educational life—including from luminaries like Zora Neale Hurston, Mary McLeod Bethune, Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Ralph Ellison, and John Lewis, LL.D. ’12—School Clothes “explores what it has meant to be a black student in the American school,” Givens told Tuesday’s audience. “For so long, black students have been written about and held under a microscope, picked and prodded as specimens for study. They have been held in a prolonged gaze, and rarely have those gazing felt the risk of black students looking back.”

During the discussion, which was hosted by the Radcliffe Institute and introduced by Vice Provost for Special Projects Sara Bleich, Givens spoke with author and poet Clint Smith, Ed.M. ’17, Ph.D. ’20, about the book’s major themes and discoveries. Picking up Givens’s image of the book as an “intergenerational chorus” of voices, Smith said that, reading it, “I could hear Phyllis Wheatley talking to the folks of the civil rights movement…I could hear the students of 2010, or 2023, being able to put their experiences in conversation with the students of generations that preceded them.”

The two men spoke about the concept of the “veil,” described by W.E.B. DuBois, A.B. 1890, Ph.D. 1895, in The Souls of Black Folk, which helped guide Givens’s understanding of the narratives he was encountering in the archives and in interviews. They talked about how black leaders’ early educational experiences profoundly influenced the civil rights movement and the formation of black studies as a discipline. And they discussed Givens’s decision to incorporate his own educational experience into the book, as a black student of black teachers from preschool through high school. School Clothes opens with an extended account of his eighth-grade teacher, Miss Paige, who grew up in Louisiana and attended a segregated school there before moving to California, where Givens came to know her. “There was no way to remove my own personal experience” from the book, he said. “I needed to place myself in that tradition, because in many ways, this scholarship that I’m producing and my work as a black intellectual is an extension of a history of black students trying to think otherwise in the world.”

The book is arranged chronologically, beginning in the early nineteenth century but also thematically, he explained. “My goal was not to create an encyclopedia of every single student perspective I came across,” but to highlight important and recurring ideas: about desegregation, literacy, political activism, the conflicts between education and racial capitalism. “Bringing them together really helped emphasize things that get at universal aspects of black student experiences across time and place,” Givens said. One of his sources was a memoir by playwright, scholar, and civil rights activist Ida Mae Holland, who grew up in Greenwood, Mississippi, and recalled being a child in 1955 when Emmett Till was lynched there; she knew the black undertaker who cared for Till’s body. Another source for School Clothes was a diary kept by 16-year-old Charlotte Forten, who attended an integrated school in Salem, Massachusetts, during the 1850s and witnessed the apprehension of a fugitive slave who was sent back to bondage in Virginia. She was the only black student in her class, and her diary records her own horror and sorrow, and her frustration at the lack of outrage from her teacher and classmates.

“There’s an interrelationship,” Givens said, between Forten’s experiences and Holland’s, and “In my mind, those narratives harken to the experiences that black students in the contemporary moment have when they have to witness the wide circulation of recorded killings of black people that have happened repeatedly over the past few years. It’s this kind of ritualistic encounter that black youth have, that they have to make sense of themselves in relationship to.”

Toward the end of the conversation, an audience member asked Givens to comment on recent upheavals in Florida, one of many states with a growing number of book bans, where Governor Ron DeSantis, J.D. ’05, and the Republican-controlled legislature have passed laws curtailing classroom instruction and student reading material. Last week, in response to DeSantis’s policies, Florida’s board of education adopted new curricular standards for African American history that were widely criticized as an attempt to whitewash what students learn about the country’s racial past.

To Givens, all of this seemed familiar, the latest iteration of an old story that stretches back to Jim Crow and beyond: “What we see happening now is part of this much longer history of a violent white resistance to efforts to create more space for multiple claims on human experience to be included in the foundation of knowledge.” He recalled the response of Toni Morrison, Litt.D. ’89, to the 1990s backlash over multiculturalism in social studies education; closely paraphrasing her words, he said, “Nothing is so fought over as our approach to knowledge and its parameters.” That tug of war, he added, over “what constitutes legitimate knowledge, and whose perspectives get to shape and frame histories and the formal curriculum, is part of the way power is always embedded in education.”