The lore of singer-songwriter Gram Parsons ’69 often goes something like this: considered the “father” of country rock music, he pioneered a new genre despite never having a hit record. Parsons started the International Submarine Band in Cambridge, played with the Byrds, then cofounded the Flying Burrito Brothers in Los Angeles. He’d just released a solo album featuring vocals from his protégée, future country music star Emmylou Harris, when he died of a drug overdose in 1973. Honoring a pact Parsons and his road manager Phil Kaufman made at a friend’s funeral, Kaufman rented a hearse, stole Parsons’s body from a Los Angeles airport, and cremated it in Joshua Tree National Park—in what became the subject of a 2002 film and a macabre legend in rock ’n’ roll history.

Now, Parsons’s story is told mainly through the lens of his final years—artistically his most productive, but personally his most complicated. My father, Fred Walecki, owner of Westwood Music in Los Angeles, was friends with Parsons and cringes at how his death has come to overshadow the rest of his life. Parsons’s bandmate Ian Dunlop says, “People love the sensationalism of Gram’s story. They say, ‘Oh, Gram, he was on the road to hell, you know?’” There’s an elegiac way people talk about him that ignores the contingency of past events, as if all of it were inevitable: that he was always destined to start country rock, live hard, and die young. “Tragedy and myth and the heroic young death—there’s glamor to it,” Dunlop says, regretfully. “It’s great copy.”

But Parsons had a whole life before Los Angeles, before heroin, far from Joshua Tree and the Sunset Strip. For a brief time in 1965, he was a Harvard undergraduate in Pennypacker Hall, sitting cross-legged with his guitar on his dorm-room floor. Harvard meant something to him, and throughout his career, he returned again and again.

Southern Gothic

The joke goes that if you play a country song backward, the singer’s wife returns to him, his dog comes back to life, his employer rehires him, and he gets out of prison. Traditional country music was made by those who ached and suffered. For Parsons, they were kindred spirits.

He was born Ingram Cecil Connor III in Winter Haven, Florida, in 1946, but everyone called him “Gram.” His father, Ingram Cecil Connor II (nicknamed “Coon Dog” for either his sad eyes or hunting acumen, depending on the source), was a famous World War II fighter pilot who self-medicated PTSD with alcohol. His mother, Avis Snively, came from a family of Florida citrus magnates and, like Coon Dog, was an alcoholic. Parsons spent holidays at the Snivelys’ Magnolia Mansion inside Winter Haven’s Cypress Gardens amusement park (now the site of Legoland Florida). But he grew up mainly in Waycross, Georgia—the locale of North America’s largest “blackwater” swamp—in a single-story brick home where he carved his name on the concrete stoop.

Nine-year-old Parsons loved many things—Boy Scouts with scoutmaster Coon Dog, hunting, fishing, and football—but music became everything for him in 1956 when he stayed out late on a school night and saw Elvis perform. “He came on and the whole place went bonkers,” Parsons later said in an interview. Elvis’s music unified country, rock and roll, and rhythm and blues—and Parsons said, “It all penetrated my mind.”

He’d taken piano lessons and even written his first song (titled “Gram Boogie”), but after that Elvis concert, imitating his idol became his primary musical pursuit. He’d perform on his front porch, lip-syncing Elvis songs while his band (neighborhood kids and his three-year-old sister Avis) pretended to play instruments behind him. According to Parsons’s biographer Ben Fong-Torres, when Avis goofed off, a frustrated Gram would hold the show. “Stop that,” he’d tell her. “You just straighten up and play.”

Parsons was hardly the only budding musician influenced by Elvis, but as his freshman proctor, the Reverend Dr. James Ellison “Jet” Thomas, B.Div. ’65, M.Th. ’67, says, “I think very few people take seriously the long-term effects in Gram’s life of meeting Elvis and hearing his music.” Like his hero, Parsons was “always pushing the envelope, always seeking approval.”

In the winter of 1958, his father put 12-year-old Gram and the rest of the family on a train to the Snively mansion, where they’d celebrate Christmas, planning to catch up with them in a couple of days. Then, on Christmas Eve, while they gathered for a holiday party at Magnolia Mansion, Coon Dog committed suicide in their Waycross home. He had gotten Gram a reel-to-reel tape recorder and, as an extra present, recorded messages on it from each of Gram’s close friends. He also recorded his own message, telling Gram he loved him.

Gram and Avis were largely on their own in the aftermath. His mother remarried Louisiana native Bob Parsons and moved the family to Winter Haven, enrolling the children in local schools. The Snively family worried that Bob (a wheeler-and-dealer who leased machinery for a living) had his eyes on their fortune, and Gram’s mother fell deeper and deeper into alcoholism. “His parents were too tied up in their own problems,” Thomas says. “The emotional support wasn’t there.”

So, Gram turned to music. He learned guitar, started writing songs, and at 15, became the front man for the teenage cover band, the Legends. They’d travel in a Volkswagen bus to their gigs at sock hops and sweet sixteens, getting Florida teenagers dancing to hits by Ray Charles, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Duane Eddy. Meanwhile, he skipped so much school that he flunked out of junior year at Winter Haven High and transferred to the Bolles School, a former military academy turned preparatory school, in Jacksonville.

There, he was rarely seen without a guitar (even in class) and spent most of his time writing songs in a stone gazebo on campus, serenading the crowd that often materialized. During school breaks, he played with the professional South Carolina-based folk band the Shilos and even spent the summer with them in Greenwich Village. Alongside covers of folk legends like Pete Seeger ’40, they performed Parsons’s song “Zah’s Blues,” a gentle 1950s-style pop ballad featuring Parsons crooning like Mel Tormé. He was still a long way from country music.

Then, the day of his high school graduation, he learned his mother had died from alcoholism-related complications. “There’s never anything that can replace your parents, however much you’re looking for it,” Thomas says. “There was something missing for Gram that nothing ever really filled.”

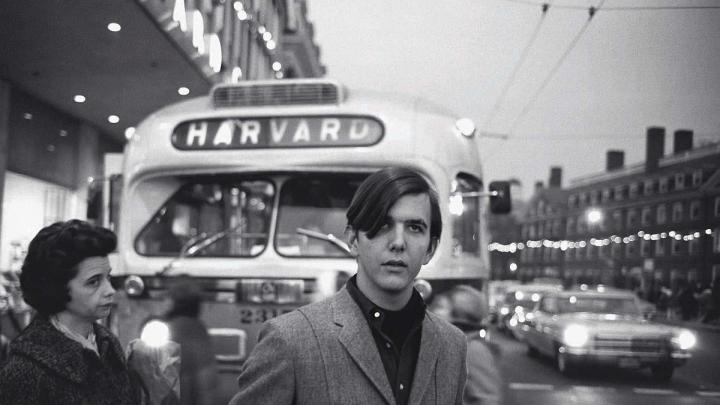

Posing with the Like, later called the International Submarine Band, on the Widener Library steps

Photograph by Ted Polumbaum/Freedom Forum’s Newseum Collection

A Harvard Man Rediscovers Country

He arrived at Harvard in 1965, driving over the speed limit in his Austin-Healey 3000. Within days, he’d posted flyers around campus looking for bandmates, and within weeks, he’d put together the Like, later called the International Submarine Band (ISB). Besides Parsons on lead vocals and rhythm guitar, the band featured local professionals: ’50s-style rock ’n’ roll guitarist and saxophonist Ian Dunlop, R&B drummer Mickey Gauvin, and rock guitarist and country music aficionado John Nuese. With Parsons still steeped in the Greenwich Village sound, their music combined “Gram’s kind of dripping, romantic lyrics,” Dunlop says, with rock and R&B arrangements. It was an uneasy blend at first, but it would take a while in Cambridge before Gram found his real sound.

As carefully as he constructed his band, he constructed his reputation. The group had barely gotten off the ground when he told a Crimson reporter that they’d secured the largest record deal in the history of RCA Records—second only to his hero, Elvis. There was a smidge of truth to this (RCA had agreed to record their demo), but Parsons spun it into such an extravagant tale that a LIFE photographer conducted an on-campus photo shoot with the band. Parsons told a Boston Globe reporter that when he wasn’t studying, he was fielding calls from Ed Sullivan Show bookers and his close friends, the Beatles. “I’m sort of best friends with George,” he said in the first-year campus publication, The Yardling. “Although, I don’t know, now that he’s married, if we’ll raise as much hell.” His classmate David Kaiser ’69 remembers Parsons saying the Beatles song “Michelle” grew out of a song he and Paul McCartney developed, but Parsons’s friends agree that this was a classic Gram fish tale. Founding member of the Eagles Bernie Leadon says, “Gram wanted those things to be true. He was creating his own myth.”

Parsons found a kindred spirit on the second floor of Pennypacker Hall in his proctor and fellow Southerner, Rev. Thomas. Today, Thomas is a genial, mustachioed philosophy and religion professor emeritus of Marlboro College, but in 1965, he was a clean-shaven Harvard Divinity School student just a few years older than Parsons. “Gram adopted me,” he says. “I fit one of those pseudo-father, older-brother-figure roles in his life. He wanted me to be proud of him.”

Parsons later joked he only got into Harvard because the College “figured they had enough class presidents and maybe they needed a few beatniks.” But as a well-coiffed graduate of a top preparatory school and a voracious learner, he wasn’t completely outside the mold. (“good books are a gas,” he wrote in his signature lowercase style to his sister, instructing her to read and compare the dramas of Shakespeare and Arthur Miller.) “Gram’s time at Harvard was basically Gram using Harvard for his purposes. It filled a crucial role in his life,” Thomas says. “It got him out of that whole family situation in the South—as far as he could get.” Still, he’d often show up at Thomas’s on-campus apartment crying, worried for his sister stuck in the Florida turmoil. Parsons felt the world deeply, and Thomas says, “Sometimes, it all got to be too much for him.”

Together in Thomas’s living room, they’d listen to the old-school country, Southern Baptist hymns, and gospel music of their childhoods. “Country music had become sort of déclassé. It wasn’t the music of the time,” Thomas says. As members of the 1960s youth movements made rock and folk their anthem, country was the hokey soundtrack of their parents’ generation. “But this was the time when Gram was reconfiguring his interest in country music,” Thomas says. He was drawn to the way its melodies opened space for poetry.

At Harvard, Parsons said, “I passed my identity crisis and came back to country music.”

“It’s a beautiful, beautiful idiom that’s been overlooked so much, man,” Parsons said in an interview in the 1970s. Gram spoke with a country accent and an unusually soft voice, like a bashful Old West outlaw. “So many people have the wrong idea about it,” he added. “God, I just can’t believe it when you say, ‘country music’ to people, what some people think—how little they know, what they haven’t listened to, what they’ve missed.”

Parsons’s fellow first-year Jim Thomason ’69 once asked him why he was at Harvard if he wanted to be a musician. “To meet interesting people like you,” Parsons replied. But he and his ISB bandmates were so busy shifting their sound toward country music and schlepping to New York City to record demos that Parsons rarely did his coursework. By the end of that fall 1965 semester, Thomas knew Parsons needed to pursue music full time. He arranged with College administrators that Parsons would leave school, but could return if ever he wished. “Harvard meant something to Gram, and it always did. It represented another possibility in his life,” Thomas reflects. Later, whenever Parsons worried that he might not make it in music, he’d call Thomas from Los Angeles: “I can still come back to Harvard next year if I want, right?”

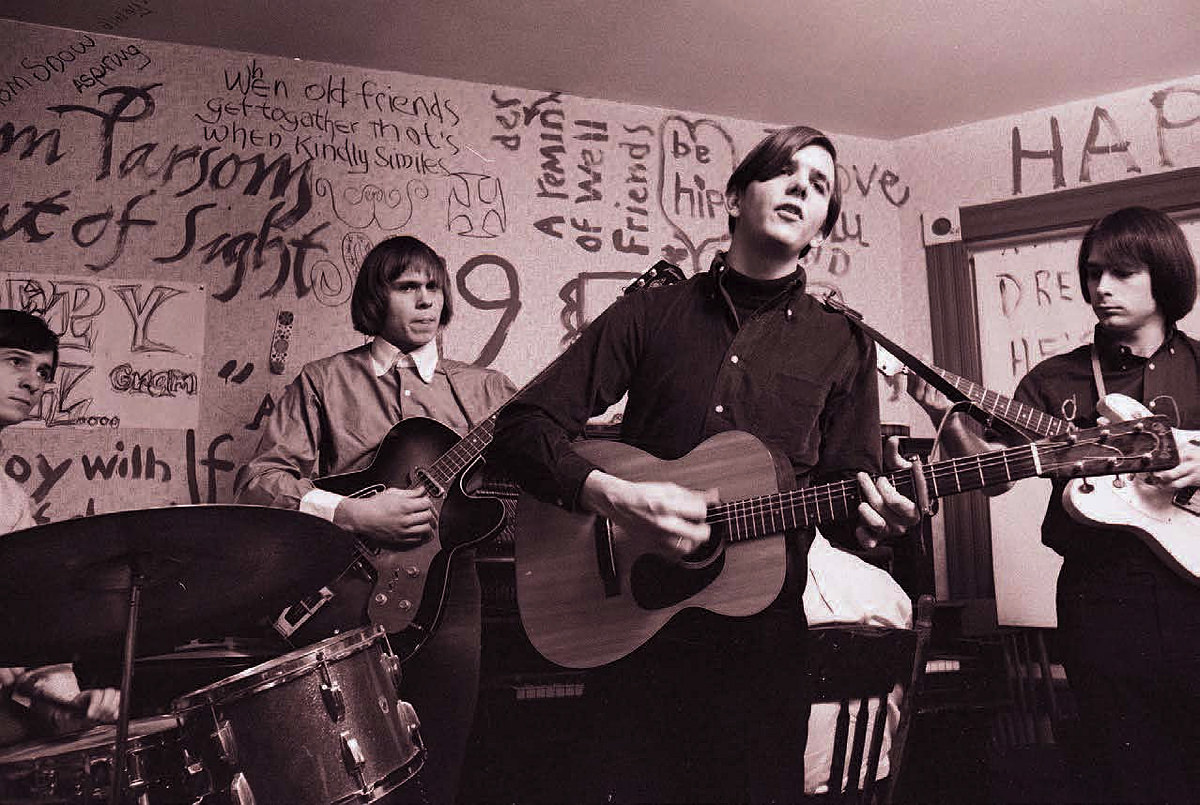

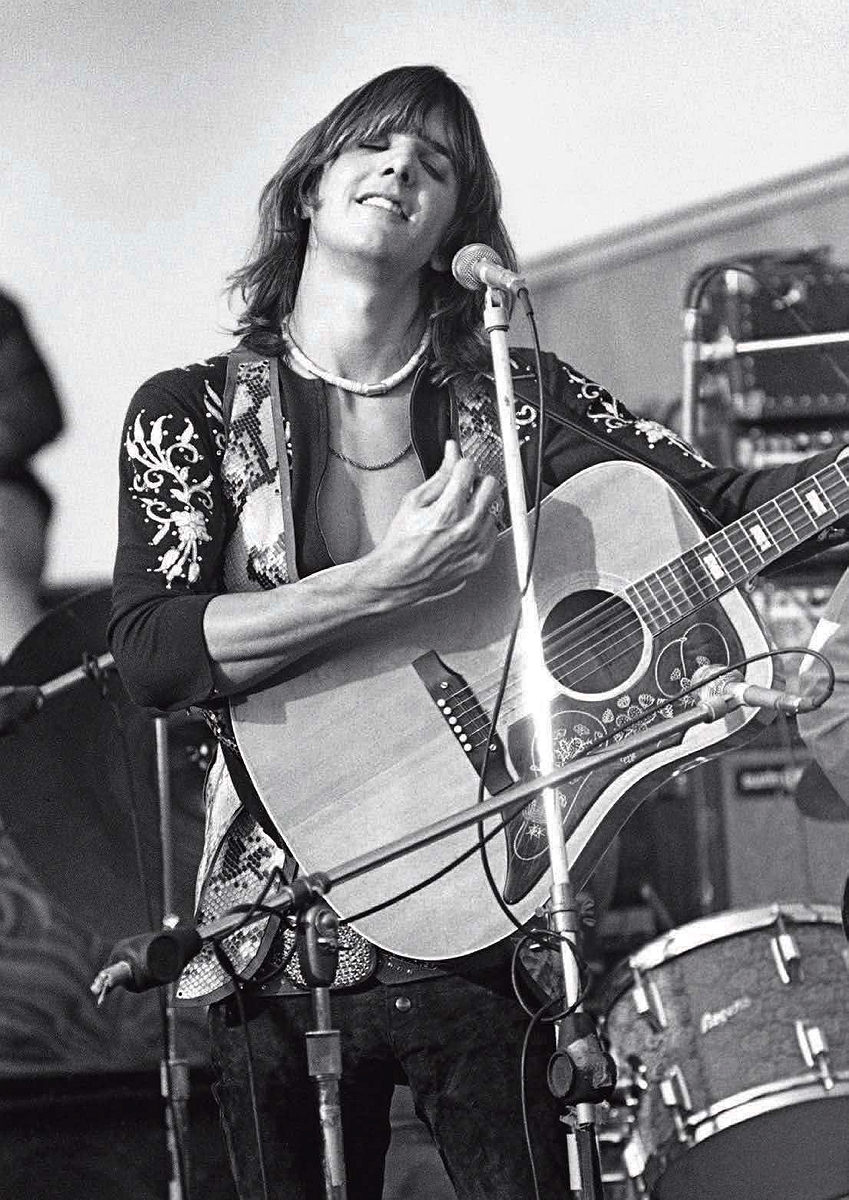

Performing with the Like in the Pennypacker basement

Photograph by Ted Polumbaum/Freedom Forum’s Newseum Collection

“I think I was there about four hours and fifteen minutes,” Parsons said about Harvard in a 1972 interview. “I hardly got my clothes hung up.” But those nights in Thomas’s apartment listening to traditional country music, gospel, and the new, gritty Bakersfield sound from westerners like Merle Haggard—those nights fertilized something that had been planted long before. “Gram rediscovered country,” Thomas says. “Harvard for him was a space in his life, a transitional space from all that stuff in Florida and a transitional space where he reconfigured his interest in music.” At Harvard, Parsons said, “I passed my identity crisis and came back to country music.”

Cosmic American

Every musician has influences, but Parsons was deliberate about synthesizing his. He wanted to combine the country music he loved with the modern, poetic lyrics he wrote, and the rock-star persona he embodied. He called this country rock synthesis “Cosmic American Music”—a highfalutin term he later deemed a relic of his “earlier college days.” The goal was to create a geographically, racially, and generationally desegregated sound. “I don’t know if I’m playing with fire or if I’m doing the right thing even,” he once said in an interview. “I think I am. When I say that longhairs, shorthairs, people with overalls, people with their velvet gear on can all be at the same place at the same time for the same reason, that turns me on.”

With Parsons out of his folk phase, the ISB relocated to Los Angeles and developed a sound it called “country-western rhythm-and-blues.” But while critics like Robert Christgau admired it, neither country nor R&B fans bought in. “Nobody understood it,” Parsons later said, “and we were some nuts anyway.”

But he’d taken to Los Angeles. He tapped into what Dunlop called the “Boy Scout Gram” with frequent camping trips in Joshua Tree, and he fell in love with L.A.’s music scene. “That’s when it was all happening,” Parsons said. He’d drive to Snoopy’s Opera House in the San Fernando Valley to hear Delaney & Bonnie Bramlett. “That’s where the idea for big-time country music started hitting me,” he recalled. “I started seeing that it could be done again, that these guys were gonna make it.”

In 1968, what would have been in junior year of Harvard, his life changed in a Los Angeles bank. There, he ran into Chris Hillman, cofounder of the Byrds—a band that had pioneered its own hybrid genre, folk rock, with their hit “Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man.” As luck would have it, they needed someone to fill in on keyboard. Parsons wasn’t much of a pianist, but he floored the group with his original songs. Soon, he was playing rhythm guitar and writing songs for one of the nation’s biggest rock bands.

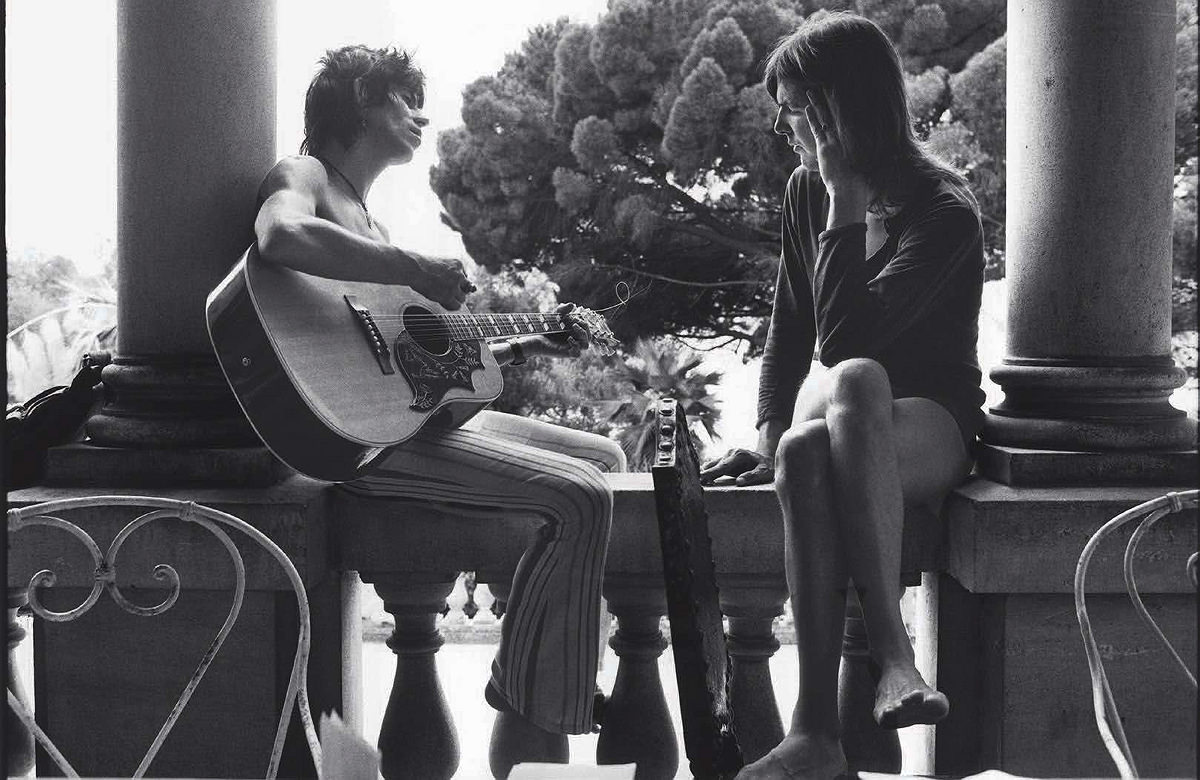

Richards and Parsons at Villa Nellcôte in France, where the Stones recorded Exile on Main Street.Richards said he and Parsons hoped to collaborate one day: “We thought we had all the time in the world.”

Photograph by Dominique Tarlé/San Francisco Art Exchange (www.sfae.com)

With Parsons in the mix, the Byrds brought the undercurrent of country music in their earlier work to the surface. The Sweetheart of the Rodeo album featured two Parsons originals, including “Hickory Wind,” in which the protagonist yearns for his Southern childhood. On lead vocals, Parsons sang sadness: “It’s a hard way to find out / that trouble is real / in a faraway city / with a faraway feel / But it makes me feel better / each time it begins / callin’ me home / hickory wind.” Sweetheart would one day find its audience, but 1968 was not that time; country purists booed the Byrds when they performed at the Grand Ole Opry. But as Keith Richards wrote in his autobiography, “That record, which bemused everybody at the time, turned out to be the incubator of country rock.”

“It's hard to describe how deeply Gram loved his music. It was all he lived for,” Keith Richards remembered. “And not just his own music but music in general.”

Parsons returned to Harvard with the Byrds that year, showing them around campus. “He was practically preening,” Thomas laughs. They performed “Jesus is Just Alright” for the Rev. Thomas in his living room, and among the audience was Ernie Brooks ’71, who’d later play bass in the early punk rock band the Modern Lovers, and Jerry Harrison ’71, who’d play in the same group and later pioneer New Wave music with the band, Talking Heads. Thomas says, “Gram definitely wasn’t the only talented person at Harvard.”

The Flying Burrito Brothers (left to right) Michael Clarke, Sneaky Pete Kleinow, Chris Ethridge, Chris Hillman, and Parsons lounge in their Nudie suits while off duty in Topanga Canyon, outside Los Angeles.

Photograph by Jim McCrary/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

A Byrd Flies to the Burritos

Within months of joining the Byrds, Parsons left. Depending on the source, he either quit because of a principled stance against touring in South Africa during apartheid or because he wanted to spend more time with his new friend Keith Richards and his band, the Rolling Stones.

He and Richards shared drugs, but they also shared music. They’d spend days listening to George Jones and singing Everly Brothers harmonies. “Gram taught me country music—how it worked, the difference between the Bakersfield style and the Nashville style,” Richards remembered in his autobiography. “Some of the seeds he planted in the country music area are still with me…I know I’ve had a good teacher.”

Parsons’s offbeat way of thinking manifested musically. He’d tell Richards, “I’ve been writing about a guy who builds cars,” but it’d turn out to be the melancholy tale of E.L. Cord, who painstakingly designed the artful Cord automobile only to be crushed by the mass-produced Ford. Richards wrote, “He could write you a song that came right round the corner and straight in front, up the back, with a little curve on it.”

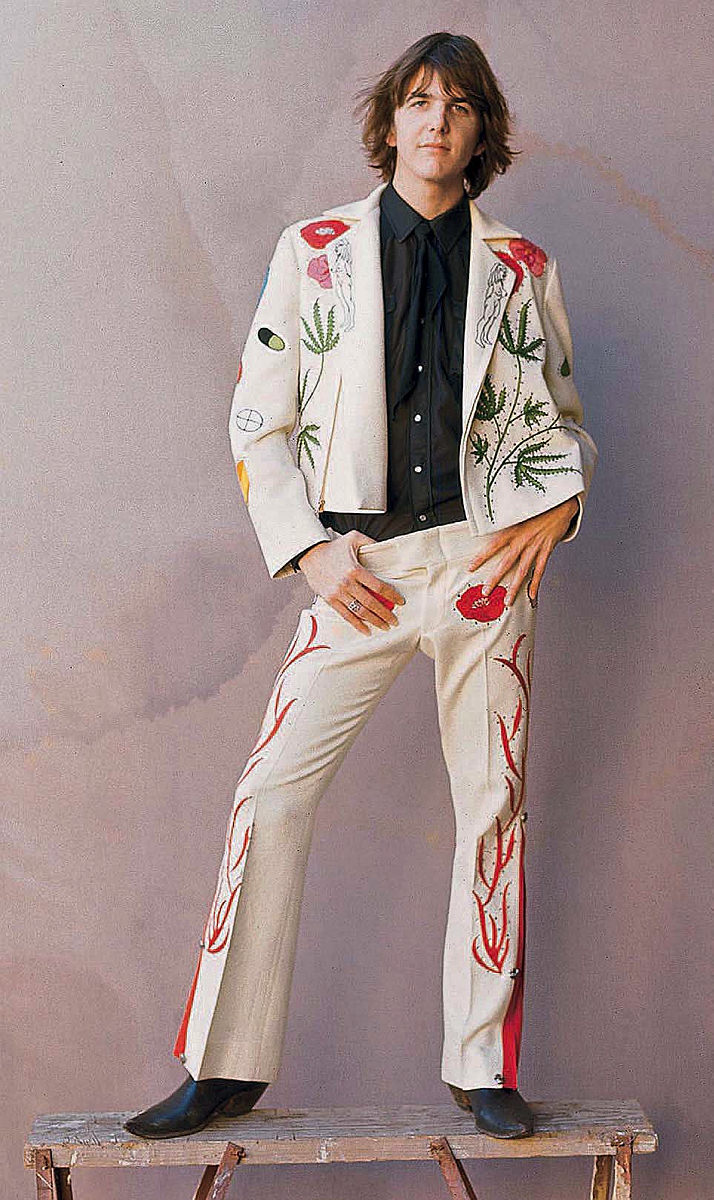

Parsons and his Nudie suit brainchild.

Photograph by Jim McCrary/Redferns/Getty Images

A testament to Parsons’s talent, and perhaps his charm, Chris Hillman agreed to start a band with him just a few months after his dramatic Byrds exit. “Since Gram and I shared a common vision to bring real country music to a rock audience with a hip sensibility, we agreed it would make sense for us to join forces and carry on from where Sweetheart left off,” he remembered. Together, they formed the Flying Burrito Brothers, a band whose name was outdone in peculiarity only by its music. For the cover of their debut album, The Gilded Palace of Sin, the band—Hillman; former ISB bassist Chris Ethridge; and pedal steel guitarist and full-time animator for the television show Gumby, “Sneaky” Pete Kleinow—posed in Joshua Tree wearing customized Nudie suits, a country-western musician’s staple. Parsons chose to embroider his with a southwestern style cross, rhinestone-studded marijuana leaves, and sugar cubes laced with LSD. As Bernie Leadon says, “Talk about a cross-pollination of influences.”

The album was country music seen through a kaleidoscope. It set Parsons’s and Hillman’s apocalyptic lyrics to tender country melodies and Sneaky Pete’s novel overdubbed and distorted pedal steel. Songs like “Sin City” contended with the vacuity of Los Angeles and, perhaps, the nation at large: “The scientists say / It’ll all wash away / But we don’t believe anymore / ‘Cause we’ve got our recruits / And our green mohair suits / So please show your I.D. at the door.” The chorus admonishes: “It seems like this whole town is insane / On the thirty-first floor, a gold-plated door / Won’t keep out the Lord’s burning rain.” Their music was old-school country after swallowing a dose of 1960s strangeness.

During Parsons’s Burritos era, Thomas left Harvard to write his dissertation in a cabin on Mount Baldy outside Los Angeles. Now more of an older brother to Parsons than a proctor, he would take study breaks with him in town: “It was a whole different world from Heidegger and Wittgenstein.” Once, they met Janis Joplin in a nightclub parking lot. “This is my adviser from Harvard. He’s into phenomenology,” Gram said. “Wow,” replied Joplin. “I believe in ghosts, too.”

Parsons at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival in 1969 with the Flying Burrito Brothers. What was intended as a Woodstock-style festival quickly turned violent when Hells Angels security guards killed a concertgoer.

Photograph by Robert Altman/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

A Song for Dallas Hext

The last time Parsons visited Harvard was as a solo artist. As his drug addiction worsened, Hillman felt he had no choice but to fire Parsons from the Flying Burrito Brothers. Gram made his next album in 1973, featuring harmonies by the then-unknown singer Emmylou Harris. With Parsons as her guide, “My ears and my heart opened up to country music,” she told Dan Rather. “I really heard the genius of George Jones, the beauty of Louvin Brothers harmonies, the poetry of country music, the stuff that’s deep in the weeds, the washed-in-the-blood stuff.”

The two performed at Oliver’s in Boston, and Thomas, by then the senior tutor in Adams House, brought along Dallas Hext, a sixty-something widow and the administrative assistant to the Adams Faculty Dean. Parsons got them the best seats in the house and sang the Bob Dylan song “Lay, Lady, Lay” directly to Hext. “She loved it,” Thomas remembers. “He made her feel like she was just the most important person in the world.” Parsons could be difficult and vexing, but he was also, as Harris once said in an interview, “a beautiful, generous, sweet, very loving soul.”

Parsons and Harris left Cambridge and continued what would be a legendary partnership, recording an album of duets, Grievous Angel. Shortly after, in September 1973, Parsons was trying to get sober when he accidentally and fatally overdosed in the Joshua Tree Motel. He was 26.

The Father, The Dreamer

Identifying the “father” or “mother” of a musical movement is a tricky thing. As country music historian Bill Malone said, “Just when you think you’ve found the person at the beginning of a trend, you look a little deeper and find, well, there’s somebody who came just before him.” But it wouldn’t be presumptuous to say that Gram Parsons was the father of country rock.

He was country’s evangelizer and cross-pollinator. “He pioneered the synthesis of country music, rock drums and bass, distorted pedal steel guitar, and rhythm and blues,” the Eagles’ Bernie Leadon says. Richards wrote, “He showed [listeners] a new approach, that country music isn’t just this narrow thing.” Beyond Harris, the leaders of the alternative-country movement like Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy credit Parsons as their lodestar, and Richards said listeners can hear his country tutelage in Rolling Stones songs like “Wild Horses” and “Sweet Virginia.” But Parsons’s country rock style perhaps reached its widest audience through one of the most famous bands of the 1970s. As Leadon says of the band he cofounded, “The Eagles commercialized what Gram synthesized.”

Parsons and Harris on their final tour together in 1973. “I was the beneficiary of the fact that he went before me,” Harris said. “I just had to figure out how best to continue.”

Photograph by Jeff Hochberg/Icon and Image/Getty Images

“It’s hard to describe how deeply Gram loved his music. It was all he lived for. And not just his own music but music in general,” Richards remembered. “He’d be like me, wake up with George Jones and roll over and wake up again to Mozart.” He needed music. “I don’t think he made deep connections with other people that easily,” Thomas says. “Music was the primary means he had of relating to people across that gap.” Few people ever truly got to the heart of Gram, and if they did, it was through his music.

He was mercurial, conceited, and reckless, and sometimes he broke his friends’ hearts. He was also extremely bright, funny, a perceptive songwriter, and a devoted brother. Perhaps there’s only so much one can extrapolate about who Parsons really was. There’s only so much room for a redemptive arc when a person dies at 26. And as Parsons himself once said in an interview, “You can’t be all bad if you’re doing something for country music.”

Sound as Ever, Gram

When Parsons was still at Harvard, he took great care writing letters to his sister, reading them aloud to Thomas before he sent them. Typed in lowercase on Harvard stationery, they’re bits of the bright-eyed Parsons often forgotten in elegiac retellings of his story. On November 8, 1965, not long before he left Harvard, he told her:

the best thing we can do is learn from the past and live our lives the right way so, in time, when we can do something to change things, we will be real people. not sick or haunted by what life has done to us. […] i know we love each other, maybe we don’t say it enough because we’ve seen love twisted so many ways, but i hope you’ve never doubted it. [...] i can’t convey what a blessing a place like harvard is. there are so many wonderful brilliant people here. i just hope you have the chance to go to some really good schools. [...] above all—believe in yourself—and in other people—they’re the only thing that is real. i’ll try to write as often as i can. until then–live your life as you see it–as best you can–give it a solid foundation for the future.

sound as ever, gram