The first time I moved to Harvard, I stuffed my suitcases with things I knew I’d never need: glittery lanyards, quill pens, a pack of Big League Chew bubblegum I’d been gifted by a friend as part of a Boston-themed high-school graduation present. My mother made a last-minute shopping trip to the Target in Central Square and naïvely bought me an iron and ironing board, which sat idly in the corner of my dorm room before I sold them to another student the following year. My Amazon order history from late 2017 is a miscellany of items I’ve since discarded: a bulletin board, a printer, a foldable drying rack. I sold the first, abandoned the second on a Cambridge street corner after it jammed, and don’t know what happened to the third.

Both my parents accompanied me to campus that fall. With hotels and Airbnbs in and around Harvard Square completely sold out during move-in weekend, they were forced to stay near Fresh Pond. On move-in day, they maneuvered their rental car past Johnston Gate and into the Yard to unload oversized items in front of Canaday Hall, where I soon learned I would reside in a walk-in-closet-sized, stand-alone single bedroom on the third floor. My horror at my unsightly accommodations was overpowered by the infectious exuberance of the three Peer Advising Fellows (PAFs) and resident proctor who stood at the building entrance, dancing to upbeat music pulsing from a speaker and welcoming me and my classmates inside.

Though I was unimpressed by my first-year housing, I was captivated by the inviting atmosphere that the PAFs had forged, and the sense of community I was sure would emerge from living among my entrywaymates. The campus bustled with freshmen and upperclassmen, many exchanging emotional goodbyes with family members. The weather was kind, floating in the mid 70s with a feathery breeze. The lush grass shimmered, and colorful Luxembourg chairs were sprinkled across the Yard, where we sat and mingled. It was a halcyon start to the fall semester.

In subsequent years, I managed to reduce the number of boxes I lugged to the Adams House basement every May to store over the summer. By junior year, I could fit everything I owned into six cardboard boxes, which I stored at a relative’s house before leaving campus abruptly last March. Since then, I’ve been home for almost a year, until late last week, when I moved back to Harvard for a final time.

Unlike previous journeys, I took this one alone: my parents stayed in Tucson because of post-travel quarantine requirements. I rented a Zipcar to retrieve my belongings from my relative’s house. But when the car wouldn’t unlock on the morning of my move, I found myself Ubering from the house to campus with a driver who was generous enough to help me load and unload the boxes I’d somehow managed to fit into the trunk of his SUV.

The weather was dreary. Gray rainclouds painted the mid afternoon sky, eclipsing any evidence of sun—the same sun that perennially sparkled over the Arizona desert. A gossamer layer of snow blanketed the ground from the previous night’s showers. As the day slipped into a quiet darkness, I coveted the August weather I’d relished during my very first move to campus. Sitting in the back of my Uber as it approached Harvard Square, I observed tourists and locals alike ambling the streets, but the students were invisible, either corralled in their dorms for mandatory quarantine, living off-campus on Harvard’s “shadow campus,” or entirely absent—not allowed back in residence for spring semester. Local businesses had been ravaged by the pandemic: among the losses, the bohemian Café Pamplona, across from my dorm.

Before moving in, I checked in at the Science Center, where students received nasal swabs, a wristband, and a bag of microwaveable meals for our first 24 hours after move-in, during which we all had to remain in our dorm rooms. Expecting a long line, I instead encountered only two or three students in front of me. I recognized one of them, another Adams House senior whose eyes crinkled, upon seeing me, into what I imagined was a smile under her blue face mask.

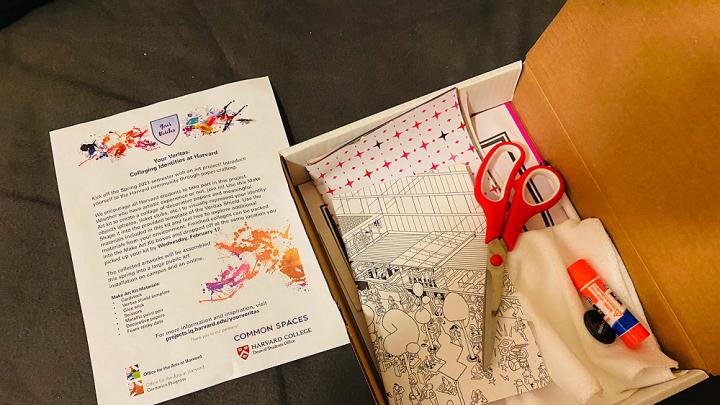

When I arrived at Adams House, I picked up my key from the mailroom and was presented with a small cardboard box filled with collaging supplies. “Introduce yourself to the Harvard community through paper-crafting,” an instruction manual inside the box encouraged me, explaining that the collages would be assembled into a public art installation this spring. It wasn’t the welcome I’d experienced freshman year. But it was a welcome attempt at fostering some sense of connection remotely.

I had my own suite in Adams’s majestic Westmorly Court, across the hall from where Franklin Delano Roosevelt lived as an undergraduate. It was a regal upgrade from my freshman year in Canaday, where I shared a dingy bathroom with nine other women. Yet I still felt a lingering sense of loss. Perhaps it was because my last semester as an undergraduate had just been inaugurated by a largely quiet and isolated move-in, sans the bubbling excitement of the previous three. Or perhaps it was because, unlike freshman year, I hadn’t met my neighbors—and was effectively barred from knocking on their doors and introducing myself. My only social interactions this semester would be planned in advance with close friends, and largely limited to the bleak outdoors until restrictions on socializing are lifted and the weather improves.

After the first 24 hours of quarantine in my room, I took a brief walk outdoors. I lapped the Adams House buildings, walking from Mount Auburn Street, up Plympton Street, across Massachusetts Avenue, and down Bow Street as my fingers grew red and raw. Expecting to see a handful of fellow students also out and about, I was shocked when I recognized no one on my walk. Perhaps that was due to the cold. Still, I craved in-person company and the cozy feeling of community Harvard had gifted me as a freshman.

Nevertheless, standing in my new room that chalky winter afternoon, I was grateful. During a pandemic, Harvard had shown me love, manifested in a fledgling art project aimed at kindling community—and in the heavy brown bag of food I’d picked up in the Science Center and the hodgepodge of snacks and water bottles I discovered waiting for me in my dorm room, along with neatly packaged boxes of face masks and sanitation supplies. Someone cared. This time, I just couldn’t see that person, face-to-face.