One spring day in Las Vegas, adventure-writer David Roberts ’65 set out for a round of golf with Alex Honnold, the world’s foremost free-soloist. More than a generation apart, the two men have shared a fanatical drive to ascend, and grew close while co-writing Honnold’s 2015 autobiography, Alone on the Wall.

The younger climber, who scaled Yosemite National Park’s El Capitan without any gear, had never set foot on a green, but quickly found his stride: “To me, the pleasure of the sport was to whack the ball as hard as I could, every time—give it 100 percent—just to see it shoot across space.” Roberts, Honnold says, was more of a stickler for proper form and rules, and though weakened by cancer, he “still really wants to win.”

Roberts has won a place in history for his Alaskan explorations in the 1960s and 1970s; he and fellow Harvard Mountaineering Club climbers named the Revelation Mountains, after spending 52 straight days in that forbidding landscape. During the last five decades, Roberts has earned plenty of other accolades for his edgy, obsessively researched, impassioned contributions to exploration literature—hundreds of articles and essays, and more than 30 books. Raw accounts of two early expeditions, where a friend died, and Roberts spent 40 days on a harrowing failed ascent, turned his first volumes, The Mountain of My Fear and Deborah: A Wilderness Narrative, into new kinds of classics. Eschewing the traditional macho heroism, Roberts’s riveting portrayal of climbing delves into dark caves of egotism, fear, and doubt. “David has never stopped asking the hard questions about climbing—chief among them, ‘Is it worth the risk and inevitable suffering?’” says his longtime agent, Stuart Krichevsky. “At one end of the spectrum is his famous 1980 Outside essay ‘Moments of Doubt’; at the other is his 2005 memoir On the Ridge Between Life and Death, in which he reckons with the ripple effect that tragic accidents have had on others—survivors, climbers, or loved ones.”

Stark queries into the purpose of life, and art, are woven throughout all his books, from those he coauthored with fellow climbers Ed Viesturs, Conrad Anker, and Brad Washburn ’33, L.H.D ’75, to his biographies of the brilliant, damaged writer Jean Stafford and the artist-poet Everett Ruess, who disappeared in 1934 while traveling alone in the remote desert of Escalante, Utah. The Southwest so entranced Roberts that since the early 1990s he’s spent spring and fall exploring its ancient beauty and chronicling its native peoples. His ninth book on the region, to be published in late February, is The Bears Ears: A Human History of America’s Most Endangered Wilderness. Amid his own desert exploits, Roberts immerses readers in this haunted, stunning place, highlighting inhabitants from Navajo leader Manuelito to notorious artifact-looter Earl K. Shumway. It’s not a polemic, but a testament to this venerated place and the continuing battle to preserve the 1.35 million acres of American heritage.

“Goddamned COVID,” he fumes during a fall interview, masked and bundled-up, outside a café near his home in Watertown, Massachusetts. The pandemic has precluded his usual travels. But even before that, throat cancer, diagnosed in 2015 and now metastasized, had hampered athletic excursions. “There’s so much physically I can’t do anymore,” he explains, “and that’s just pitiful.”

Writing, a full-time livelihood since he stopped extreme mountaineering in 1979, has become a lifeline. With three books completed while ill, including the soul-searching semi-memoir Limits of the Known, he is now tackling a biography of British Arctic explorer Henry George “Gino” Watkins. By age 25, he’d led four major expeditions before he went out hunting for seals in Greenland in 1932, and never returned. “He was an extraordinary person; I hope to resurrect him from obscurity,” says Roberts, talking between sprays to wet his throat. “If I didn’t have writing to keep me going, to keep me focused and craving to dig out meaning every day, I would feel true despair.”

Winning doesn’t much apply to writing, he says. Critical, though, is “getting it right, which means telling a certain kind of truth, even if it goes against the grain.” As for Honnold and golf, and other games, Roberts says: “I am indeed compulsive about winning. My mother was horrified when at age 11 or 12 I answered a school questionnaire that asked, ‘What kinds of friends do you like to have?’ by responding, ‘I don’t care about having friends as long as I have people I can beat in games.’” At 77, kept alive by doctors and immunotherapies at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Roberts likes to think he has mellowed. That cold-eyed youthful declaration aside, he counts many friends and adventuring buddies, along with his wife of 52 years, Sharon, a retired psychoanalyst. And for all of them, he is plainly grateful.

His oldest surviving climbing mate, Matt Hale ’66, was with Roberts and Don Jensen ’65 on the fateful 1965 Mount Huntington trip in Alaska where they lost their friend Ed Bernd ’67. Following a triumphant ascent of glacial pyramidal rock, Bernd and Roberts headed back down alone, with Hale and Jensen to follow on the next fair-weather day.

But not far from the lower base camp, something—Roberts still doesn’t know what—went wrong. Bernd rested on the rappelling rope, and suddenly flew backwards. “He hit hard ice 60 feet below,” Roberts’s Outside essay recounts. “But it was evident that his fall was not going to end—not soon, anyway. He slid rapidly down the ice chute, then out of sight over the cliff.”

Roberts clambered on down, and spent two days in a tent “drugging myself with sleeping pills, trying to fathom what had gone wrong,” waiting for Hale and Jensen to arrive.

“Some of the worst moments have taken place in the mountains….But nowhere else on earth, not even in the harbors of reciprocal love, have I felt pure happiness take hold of me and shake me like a puppy, compelling me, and the conspirators I arrived there with, to stand on some perch of rock or snow, the uncertain struggle below us, and bawl our pagan vaunts to the very sky,” the essay concludes. “It was worth it then.”

Roberts believed this, felt this, even though Bernd was the second close friend he’d seen drop to his death on a mountain. The first was Gabe Lee. Growing up in Boulder, Colorado, where Roberts first discovered the transcendent effect of mountaineering, he and his high-school friend Lee were scaling the First Flatiron when, 200 feet from the summit, their rope snagged on a downward-pointing prong. Lee climbed down the rock face to fix it, and fell.

Those accidents, the consequences of risk, have weighed on Roberts ever since. Climbers do tend to be people who, early on, are under-stimulated by daily life, he says. Yet neither he, nor Lee, nor any other serious alpinist he knows is a reckless thrill-seeker. “Alex Honnold trains manically to do what he does and calculates the edge,” explains Roberts. “And he always says that if he starts to feel fear, he knows he’s screwed up. And he controls fear and emotion better than anyone I know. That’s why he’s the best at what he does.”

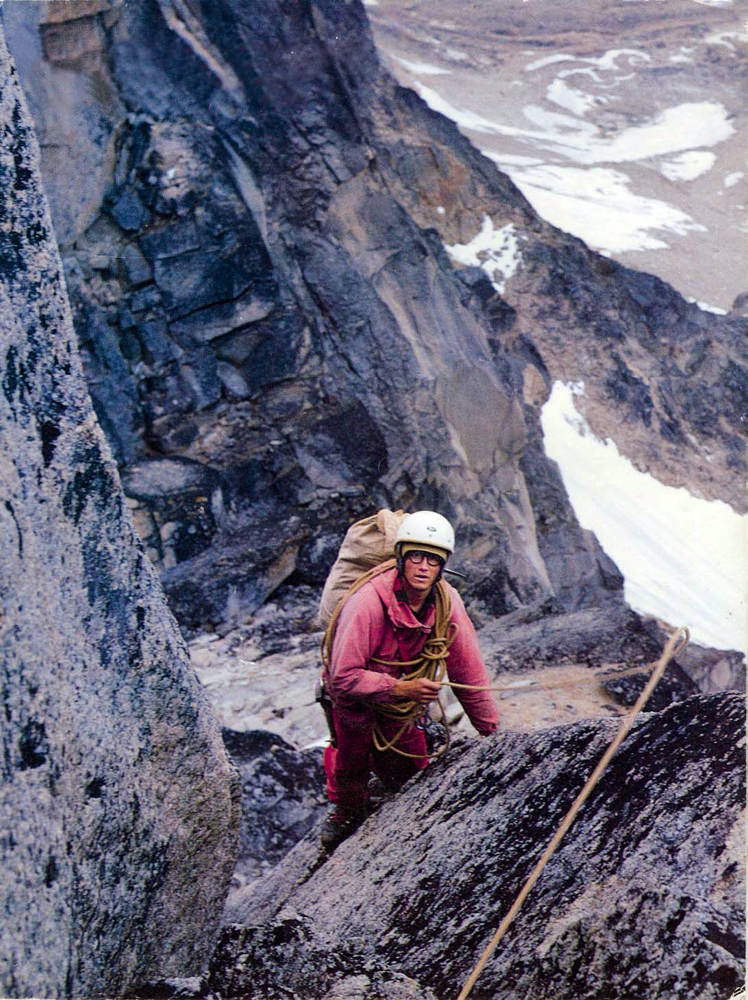

Roberts climbing the Alaskan Revelation Mountains in 1967.

Photograph by Matt Hale

Without the element of danger, Roberts adds, adventuring is just a game. What made him a climbing fanatic was the promise of “going some place that no one else had been”: exploring both the unknown physical hinterlands, but also the uncharted, psychic interiority.

He’s been a loud critic of modern mountaineering and other extreme sports. Reliance on helicopter rescue crews on deck, satellite communication, and GPS tools drives him nuts: “‘If I mess up, someone can come and save me’ is an appalling attitude.” As are inflated assertions. In 2019, Roberts was among those challenging American Colin O’Brady’s claim to have made the first unsupported, solo traverse of Antarctica, arguing in a New York Times op-ed that “For sponsored professional adventurers…true exploration becomes secondary to the need to ‘set records,’ to ‘claim firsts,’ no matter how arbitrarily defined.” He points instead to the 1996-97 sled-drawn, 64-day solo Antarctic journey of Norwegian Borge Ousland, whom he quoted: “It generally takes 10 to 14 days to find the inner harmony needed to survive in such an unforgiving world. But when it all comes together, being so totally alone is also a good experience.”

At least it always has been for Roberts. His first years were spent in Climax, Colorado, a wild place—the highest human settlement in the country. There, his astronomer father Walter Orr Roberts, Ph.D. ’40, deployed the Western Hemisphere’s first coronagraph (a telescope that artificially eclipses the sun) and developed the High Altitude Observatory. When it became affiliated with the University of Colorado, the family moved to relatively cosmopolitan Boulder.

Precocious in math, and a careful telescope-mapper of the skies, Roberts grew up with “a scientific sense of humans’ insignificance in relationship to the universe,” and was easily “bored” with earth-bound existence. By tenth grade, he had climbed nearby 2,700-foot Green Mountain some 50 times, and was eager to master the vertical, crackless slabs of the Flatirons. The disastrous trip with Gabe Lee, his less experienced friend and admirer, came only a few months before his departure for Harvard.

Stunned and guilt-stricken in Cambridge, Roberts immersed himself in math and classical music (career aspirations in both were eventually supplanted by writing), and found kinship through the Harvard Mountaineering Club (HMC). Many members, including Roberts, identified with great explorers, and got hooked on the idea of expeditions to Canada, Alaska, and the Yukon. But, he adds, “More selfishly, I always wanted to be really good at something. When I started climbing in Alaska, I realized that I could be, quote ‘world class.’ ” The club’s éminence grise, BradWashburn, urged a group to tackle the unclimbed north face of Mount McKinley (now Denali), Wickersham Wall, whipping out his stereoscopic photos of the 14,000-foot glacier-hung monolith. “‘It’s a God-awful place for avalanches,’” Roberts recalls him saying, “‘but this ridge divides them, and I guarantee that once you get on that ridge, you’ll be safe—and no one’s ever done it.’” Roberts laughs. “Well, it wasn’t safe! We had some pretty close calls. But it sure was exciting!”

Thus consumed by climbing, the following year, 1964, Roberts and fellow HMCer Don Jensen returned to Alaska to attempt, unsuccessfully, a new route on Mount Deborah. The next winter, on Mount Washington in New Hampshire, Roberts and Hale were teaching clubmates ice climbing when two other climbers fell nearby. Despite performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, Roberts could not revive the one man who still had a pulse. Only four months later, back in Alaska, he helplessly watched Ed Bernd disappear. Fueled by a purgative need, and knowing he had a gripping, true story to tell, Roberts holed up in his childhood bedroom during the 1966 spring break from his University of Denver postgraduate creative-writing program and in nine days wrote nine chapters that became The Mountain of My Fear.

He followed up with the gritty Deborah: A Wilderness Narrative (1970). By then he’d met and married his wife in Denver, earned his doctorate, and been hired as a literature professor at the newly founded, experimental Hampshire College. The academic and social freedom suited his characteristic chafing at limits. His intensity inspired students like Jon Krakauer and Chip Brown (athletic explorers who have forged successful writing careers), who also joined trips through the outdoors program Roberts developed. Like Washburn, Roberts pushed people to be bold. “He had very high ambitions for his students,” says his friend Matt Hale. “He was personable and encouraging. But he didn’t suffer fools. When teaching, there are always some number of fools, but you do what you can with them.”

Krakauer and Roberts are still close, and have long climbed together. In 2000, they undertook the emotional return to that First Flatiron where Gabe Lee died. On the Ridge Between Life and Death opens with a searing account of that awful day. Roberts returns to it at the end, describing how, decades later he finally garners the courage to speak with Lee’s siblings and a family friend. Two of them, it turns out, have always blamed him, in part, for Lee’s death—but they are also hurt and angry that he went on to narrate the incident in books and articles without consulting them. Roberts grapples with that. And he owns up to feeling relieved, and ashamed of that feeling, when Lee offered to try and unjam their rope. “Because,” Roberts says, “I never would have done that.”

At 36, past his climbing prime—and aware of a dawning gratefulness to still be alive—Roberts quit the most extreme mountaineering. He soon took a separate leap into the unknown by leaving teaching to freelance full-time, and by the 1990s was traveling 200 days a year, often across the globe—fording rivers, scaling mountains, plunging into caves, always completing stories and research at a prodigious clip, even though, his friends point out, he’s never learned to type: instead, he pokes out perfectly formed, cogent narratives one character at a time, using one finger on his right hand.

Roberts, on Muley Point, Cedar Mesa, Utah, in 2016, calls Bears Ears "My favorite place on earth."

Photograph by Matt Hale

“I am the most compulsive writer I know,” Roberts allows, but the process has never been angst-ridden. Nor has it ever replaced the fist-pumping exhilaration of climbing. That Roberts only rediscovered in southeast Utah in 1992 while reporting on an archaeological team’s effort to retrace excavations of ancient Puebloan sites: “When the story was done, I couldn’t let go.”

Soon he was spending weeks every spring and fall “archaeological adventuring” through horizonless canyonlands. He uncovered rock art, granaries, and other ruins that “nobody knew much about,” while diving as well into scholarly and archival materials, learning all he could about the ancestral Puebloans/Anasazi and subsequent Native American inhabitants: “How did they live? What were they doing here? What happened to them?” If climbing was a self-absorbed, lofty exploit, canyon-prowling felt like the opposite. One focuses on me, he says, the other, on them—the Anasazi. Sharing his trips with readers, friends, his wife, revealing the wonders of rich desert cultures, became as gratifying as any quest for a first ascent.

The goal of winning, at golf and games, finds few footholds in the glory of Utah’s deserts. And Roberts knows there’s no triumph over terminal cancer: “The cells don’t care: they just invade and proliferate.” Life, in the end, holds danger; it is not a game.

Would it be consoling to know that so much time facing and grappling with fatal risks, harnessing fear, prepares us for the natural end of the rope?

“Yeah, it would be calming, wouldn’t it?” he answers. “But I’m afraid I don’t have a comforting answer. Everything depends, I think, on whether you believe in God and/or the hereafter. If you don’t, like me, then death is truly the end, and it remains, no matter how inevitable, terrifying and in some way unknowable….Climbers cherish the illusion that they’re somewhat in control of their fate. Their manifestos gush with self-congratulatory tales of how they skirted danger or ‘cheated death.’ But we all know that the wrong falling stone or avalanche or sudden storm can snuff us out, no matter how we prepare.”

Contemplating his own last moments of consciousness, he writes in Limits of the Known, he won’t be dreaming of “the shining memory of some summit underfoot that I was the first to reach, not the gleam of yet another undiscovered land on the horizon.” Instead, he hopes for “the touch of Sharon’s fingers as she clasps my hand in hers, unwilling to let go.”