If we lived in an ordinary time, this Saturday would have seen Game 3 of the 2020 Harvard football season, with ancient and honorable non-league rival Holy Cross visiting the Stadium. Last year in Worcester, the Crimson defeated the Crusaders 31-21—Harvard’s fourth and final victory of a misbegotten season. Instead, we are resuming our cavalcade of outstanding performances with one of the most smothering displays of defense in the program’s 146-year history. It was keyed by a future governor, no less: Endicott Peabody II ’42, LL.B. ’48, whose hard hitting and keen nose for the ball helped forge a scoreless tie with favored Navy. The deadlock is arguably the second happiest draw in Harvard football annals.

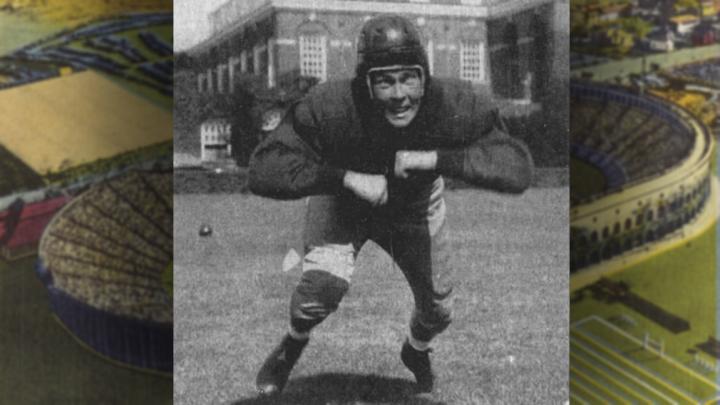

In 1941 Harvard played a power-packed schedule, equivalent to a top-tier Football Bowl Subdivision slate today. October 25, the season’s fourth Saturday, brought to the Stadium its toughest opponent, Navy. Riding the talents of hard-running back Bill Busik (nickname: “Barnacle Bill”), the Midshipmen of coach Swede Larson entered as the fifth-ranked team in the nation and would finish the season at number 10. Harvard was 1-2 and had scored seven points in three games. But oh, how the Crimson could defend. Coach Dick Harlow was a master of tactics and formations that gummed up opposing offenses. That year, Harvard also boasted college football’s smashingest guard: Endicott Peabody II.

Great (Gridiron) Performances

Great (Gridiron) Performances

Missing touchdowns? In a season without games, football correspondent Dick Friedman reprises past Crimson glories: epic plays, players, and records. Online weekly at www.harvardmagazine.com/topic/Sports

A grandson of Endicott Peabody, the founder of Groton, Peabody had two nicknames. He inherited “Chub”—a lifetime appellation—at Groton from a teacher who had first used it on his father, Malcolm Endicott Peabody, A.B 1911. The nickname hardly matched Endicott II’s physiognomy: he was a wiry 6-foot-1, 185-pounder (good size for the day). After seeing Peabody dismantle foes, Boston Globe sportswriter Jerry Nason gave him a more appropriately descriptive title: The Baby-Faced Assassin. Peabody was the linchpin of a Crimson line known as the Seven Rocks of Gibraltar. (As you can see, in those days a major part of a sportswriter’s job description was dreaming up snappy sobriquets.)

Navy cruised into Cambridge as a 4-to-1 favorite. (Point spreads were not yet in vogue.) “Poor, poor old Harvard, what a shellacking it is about to take,” wrote syndicated sports columnist Stanley Woodward, speaking for the consensus. One who took a warier view was Navy’s coach, Larson, who was aware of the havoc Harlow could wreak on his attack. In 1937 the Crimson had played the Middies to a scoreless tie. The night before the game, Larson showed his players film of that contest to try to prepare them for the Harvard coach’s schemes.

Game day was overcast and chilly. Some 40,000 fans turned out at the Stadium. The Brigade of Midshipmen was not among them. War was in the air, and the brass determined that the aspiring officers should not take the weekend off to travel from Annapolis. Early on, the Crimson defense set the tone. Harvard forced Navy fullback Alan Cameron to fumble—the first of five Middie fumbles on the day, four of which the Crimson recovered. Harvard’s Bill Barnes ’43 fell on the ball at the Navy 32-yard line. But the Crimson could not capitalize.

Later in the period came a hit that still resounds—a collision of two All-Americas. Harvard’s captain, Fran Lee ’42, punted. Busik was standing on the Navy 15 to receive. The ball arrived—and an instant later, so did Chub Peabody. Boom! In what was described as a “shattering” tackle, the ball squirted out of Busik’s hands, and the Crimson’s center, John Page ’43, fell on it. Pounding away, Harvard eventually reached the Middies’ two, but could not punch the ball into the end zone, partly thanks to a saving tackle by Busik on Harvard back Walter Wilson ’44. Why did the Crimson not try for a field goal? Harlow’s postgame explanation was that he thought his team would need more than three points to beat Navy. Which only shows that Harvard men can be dumb, too.

But in other respects, Harlow was brilliant. As described in The All-Americans, an excellent 2004 book about the navy and army teams of the cusp of war by my former Sports Illustrated colleague Lars Anderson, his main defensive wrinkle was to have his ends loop to the outside of their Navy blockers, thus forcing runners inside, where Peabody and mates such as tackle Vern Miller ’42 would be waiting. Only once did Busik break loose, on a 32-yard bolt produced mostly on individual effort. Sidestepping and stiff-arming would-be Crimson tacklers, he seemed on his way to a touchdown before Lee ignored Busik’s fake and wrapped him up at the Harvard 45. Navy reached the Crimson 15. Here Larson, too, eschewed the field goal, opting for a pass into the end zone, broken up by a committee that included Fran Lee.

In the second half Busik fumbled again, on his 31-yard line. There to beat two Navy players to the ball and make the recovery: Chub Peabody. On the ensuing drive Harvard gave the ball back when Don McNicol ’43 fumbled at the 13. That was the last, best Crimson hope. Navy’s came near the end of the game. The Middies lined up for a 52-yard field-goal attempt by Bob Leonard. The ball came thumping off of Leonard’s foot—right into the chest of the onrushing Chub Peabody. Game over.

Navy had outgained Harvard, 186 yards to 108. But those four lost fumbles, one caused by Peabody, one recovered by him, were killers. Only 22 of the Navy yards came through the air, on but two completions in nine attempts. In any case, it was futile to pass against the Crimson: for the season, Harvard finished sixth nationally in pass defense, surrendering 47.5 yards per game through the air.

Peabody had dominated. “Dick Harlow thought all his boys were magnificent,” wrote Jerry Nason. “I thought Endicott Peabody 2nd was super-wow! As of last Saturday he was the best guard your reporter has gazed upon in two or three years.”

Buoyed by the result, Harvard swept its final four games, culminating in a 14-0 victory over Yale. Peabody was a consensus All-America. Harvard would not have another All-America until 1974, when end-punter Pat McInally ’75 received the honor. Peabody finished sixth in the voting for the Heisman Trophy; he was the only lineman in the top 10. In 1973 he was named to the College Football Hall of Fame. Later graduating Harvard Law School, Peabody served as governor of Massachusetts from 1963 to ’65. He died in 1997 at age 77.

Only 43 days after the stalemate on Soldiers Field, Pearl Harbor was attacked. When the following autumn rolled around, Chub Peabody had switched uniforms. He was an officer in…the navy.

GREAT PERFORMANCES 2020. Congratulations to Crimson offensive lineman Eric Wilson ’21 upon being named a semifinalist for the William V. Campbell Award presented by the National Football Foundation (NFF). The award recognizes an individual as the best football scholar-athlete in the nation for his combined academic success, football performance, and exemplary leadership. A psychology concentrator from Minnetrista, Minnesota, Wilson was named second-team All-Ivy last season. He has started 20 consecutive games for the Crimson, going back to his sophomore year. The NFF will announce its group of 12 to 14 finalists in mid November.

October 25, 1941, Harvard Stadium: The score by quarters

| Navy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | ||

| Harvard | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 |

Attendance: 40,000 (approx.)