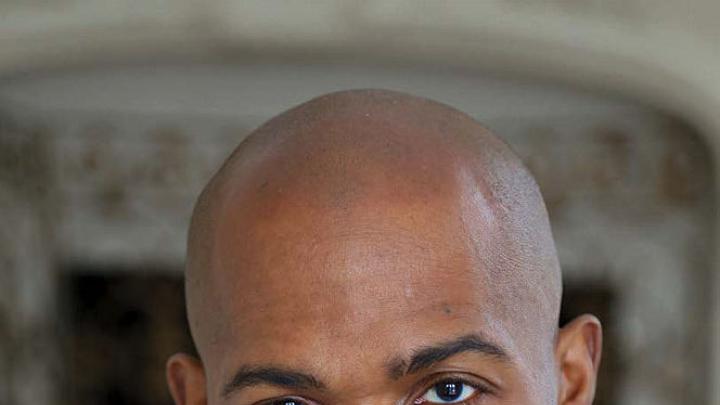

The first thriller Ian K. Smith ’91 fell in love with was The Firm, John Grisham’s wildly popular 1991 novel about a young, ambitious lawyer entangled in a Memphis firm that turns out to be a money-laundering operation for organized crime. “My aunt was a big reader,” Smith recalls, “and she and I used to read books together and then talk about them.…The Firm was so engaging that I literally found myself, at stoplights, trying to sneak in a page or two before the light turned green.” Afterward, he found his way to other authors whose mysteries he devoured: Michael Connelly, Harlan Coben, Lee Child, Dennis Lehane, Robert B. Parker, Dominick Dunne. “And I said to myself, one day, I want to write a book like that.”

Instead he went to medical school—another longtime plan—and built a career (rather than a practice) as a television and radio medical correspondent and a nutrition expert for numerous networks and shows such as The View, VH1’s Celebrity Fit Club, and The Rachel Ray Show, which he currently co-hosts. “I love the pressure of live TV—you’re so alive; there’s nothing like it,” he says. In 2010, Barack Obama named Smith to the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports, and Nutrition.

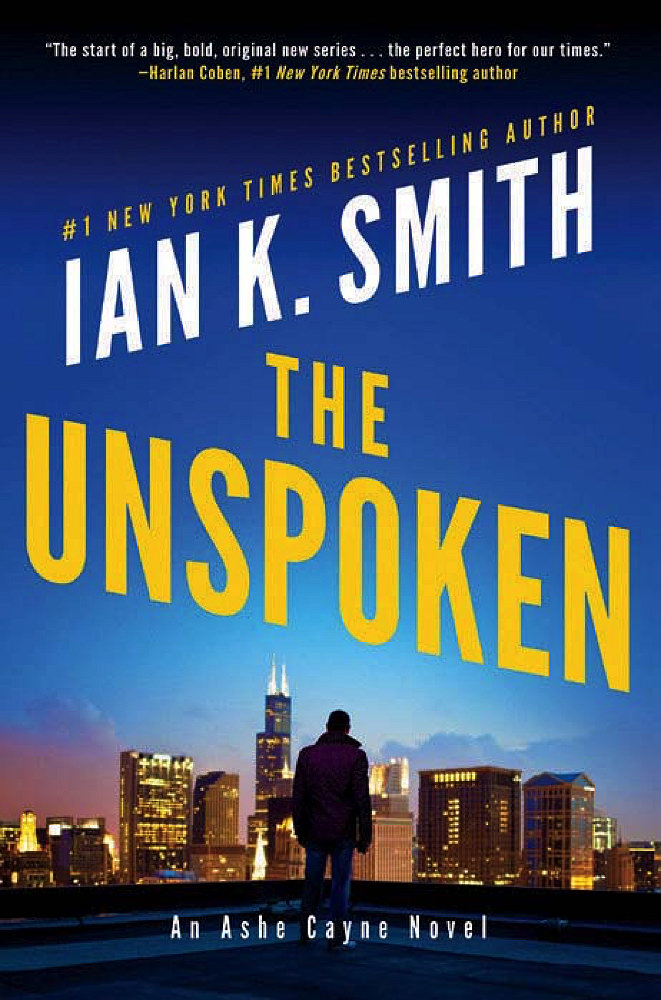

Over the years, Smith has also written a small mountain of books bristling with titles like Shred: The Revolutionary Diet, Blast the Sugar Out!, Clean and Lean, and, just this past spring, Mind over Weight. But in October, he is releasing a different kind of book, a murder mystery and detective thriller set in Chicago, where he studied medicine and now lives. It is not his first novel. In 2005, he wrote The Blackbird Papers, centering on a murdered Dartmouth professor (Smith began medical school there, before transferring to the University of Chicago), and in 2018, he published The Ancient Nine, which plumbed the dark secrets of a fictional Harvard final club.

But The Unspoken, the first entry in what will be a series, lands at an interesting moment in the national discourse. The protagonist is Ashe Cayne, a private investigator and former police detective with a sorrowful love life and unresolved issues with his psychiatrist father. Like Smith, he is African American. The story unspools how Cayne was pushed off the force some years earlier, after refusing to go along with the cover-up of police officers’ murder of an unarmed black teenager—a case that echoes the actual death of Laquan McDonald, a 17-year-old shot 16 times by an officer on the city’s West Side in 2014. When the details of that incident emerged two years later, it sparked protests, just as Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson and George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis did. “For Chicago,” Smith says, “the killing of Laquan McDonald was one of the big tipping points that really flaked off the scab and let people see there was still a wound there.” It seemed like a compelling entry point for exploring the city’s deeper layers.

Among those layers, inescapably, are race, and racism. Smith’s narrative revolves around Cayne’s search for a missing young woman, Tinsley Gerrigan, a wealthy, white North Shore heiress whose boyfriend, he discovers, is Tariq “Chopper” McNair, an African-American “one-time thug” who has turned his life around, even as his uncle still leads one of the city’s most fearsome gangs. Neither family is quite happy with the match. And Cayne himself occupies a complicated and sometimes precarious position as an African American in the law-enforcement world.

Smith’s research for the book (which has been optioned for a potential television series) began when he struck up a friendship with a security guard at his church, who turned out to be a Chicago police detective too. From there, he came to know other detectives and officers, some of them African Americans; Smith started spending time at the police station, going on ride-alongs in squad cars, hearing stories about murders and arsons and burglaries. Once he had the idea for the novel, he began spending hours researching Chicago’s history and neighborhoods. He hung out at the hospital with forensic pathologists and sat down with local politicians and city aldermen in their offices. “Chicago is such a corrupt city,” he says. “I don’t even say that in a pejorative way—Chicago works on backroom deals, and everyone has an agenda. It’s just part of what makes the city what it is. And so it was amazing research, speaking to politicians who were willing to talk to me openly.”

The novel’s publication, and the historical moment in which it appears, prompt reflection from Smith about his own childhood experiences and beyond. He and his twin brother, Dana ’92, were raised by their mother in small-town Connecticut: “Just the three of us.” The family didn’t have much money, so even though Smith loved tennis and golf, it was basketball that he played seriously. “When I was a kid, you had to pay $3 to go use a public tennis court,” he recalls. “We didn’t have $3 for a public court, so my brother and I would sneak onto the back courts. And when the court monitor would see us, we’d jump the fence and run home.”

After the twins scored well on the PSAT in high school, they began receiving letters from colleges. At one point, he says, there were five garbage bags full of them stored in the basement. One came from Harvard, though Smith didn’t pay attention to it until his uncle insisted. Soon the Crimson started recruiting him for basketball, too. Both brothers ended up playing in Cambridge: Ian as a shooting guard, Dana at point guard. Ian, with his eye on medical school, concentrated in biology.

“But you know,” he says, pivoting back to the present day, “issues of systemic racism have been around forever. I learned about them as a kid from my grandfather, who grew up in the Jim Crow South. And I’ve seen it, I’ve experienced it—African Americans talk about it at home, or at church, whenever we get together. Every adult in my life has had a bad experience with a police officer, the men particularly.” Smith’s grandfather, a World War II veteran, lived to 92, “and not one day of his life did he ever feel like others saw him as an equal. Ninety-two years. And now it’s gone. He’ll never know it.” But, he adds: “This is the first time in my life when I feel like the country is listening to African Americans. I think people are finally beginning to understand.”

As for Ashe Cayne? He’ll be back in 2021 with a new case and a new set of mysteries to solve. “I really like this character,” Smith says. “He’s flawed, but he’s also tough and big-hearted and cerebral. It feels good to be writing about an African-American lead character who represents a kind of justice in the world.”