Today, the Criminal Justice Policy Program (CJPP) at Harvard Law School released a report nearly four years in the making, on racial disparities in the Massachusetts criminal system. In October 2016, Ralph Gants ’76, J.D. ’80, chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, asked Harvard researchers to examine the vastly unequal imprisonment rates among white, African American, and Latinx defendants.

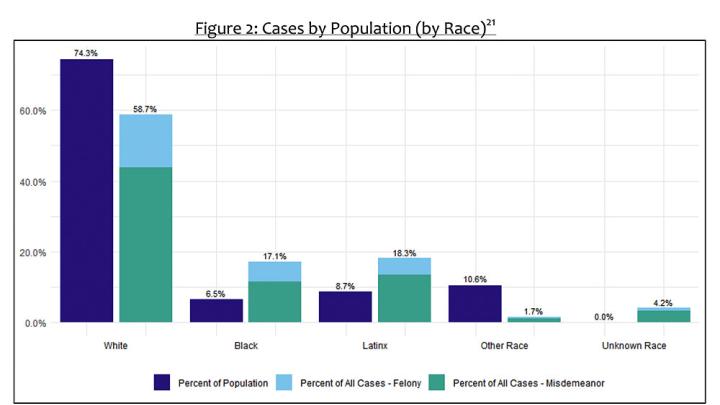

In his October 2016 State of the Judiciary address, Gants decried the “great disparity in the rates of imprisonment among whites, African Americans, and Hispanics in this Commonwealth” and pushed for “a hard look at how we can better fulfill our promise to provide equal justice for every litigant.” That fall, he announced a collaborative study with the Law School to examine the problem. The numbers that propelled Gants to act are stark: according to the Massachusetts Sentencing Commission's analysis of 2014 data, the Commonwealth far outpaced national disparity rates in incarceration; in Massachusetts, black people were imprisoned at a rate 7.9 times that of white people, and Latinx people at a rate 4.9 times that of white people. Nationally, the average rate of imprisonment was 5.8 times higher for black people than for whites, and 1.3 times higher for Latinx people than for whites.

A group of scholars at CJPP—executive director Brook Hopkins, J.D. ’04, fellows Elizabeth Tsai Bishop, Chijindu Obiofuma, and Felix Owusu—set out to understand why these numbers are so disparate. They were granted unprecedented access to Massachusetts criminal data from several agencies, including the Massachusetts Trial Court, the Department of Criminal Justice Information Services, and the Department of Correction. The data allowed the researchers to get a picture of several different stages of the criminal system, from charging and bail to adjudication and sentencing.

The researchers found that more than 70 percent of the racial disparity in sentencing length is driven by differences in the initial charges brought against defendants, which can differ significantly from the final offense they are later convicted of. Cases for black and Latinx defendants tended to have more serious initial charges than those for their white counterparts, the researchers reported. Those disparities are sometimes mitigated by adjudication and plea bargaining, but the initial-charge differences continue to influence sentencing—even when defendants of color are not convicted of the more serious crimes they were initially charged with.

In cases where the defendant was sentenced to incarceration in a state prison (in other words, cases carrying the longest potential sentences and where the racial disparity is largest), black and Latinx people are convicted of charges that are roughly equal in severity to those of their white counterparts, despite facing more serious initial charges and longer sentences. “Black people in particular who are sentenced to incarceration in a state prison,” the report states, “are convicted of less severe crimes on average than White people, despite facing more serious initial charges and receiving longer sentences.”

Studying the mechanisms that lead to these inequities, the group found that:

• Black and Latinx people are more likely to have their cases resolved in Superior Court (rather than District Court or Boston Municipal Court, which hear less serious cases), where the available sentences are longer, both because they are more likely to receive charges for which the Superior Court has exclusive jurisdiction and because prosecutors are more likely to exercise their discretion to bring their cases in Superior Court instead of District Court when there is overlapping jurisdiction.

• Black and Latinx people charged with drug and weapons offenses are more likely to be incarcerated and receive longer sentences than whites charged with similar crimes. This difference persists after controlling for factors like initial-charge severity.

• Black and Latinx people charged with crimes carrying mandatory minimum sentences are substantially more likely to be incarcerated and receive longer sentences than whites facing charges that carry mandatory minimum sentences.

In the report’s conclusion, the researchers write: “The penalty in incarceration length is largest for drug and weapons charges, offenses that carry longstanding racialized stigmas. We believe that this evidence is consistent with racially disparate initial charging practices leading to weaker initial positions in the plea bargaining process for Black defendants, which then translate into longer incarceration sentences for similar offenses.”

The full report can be read here.