Peter H. Wood ’64, Ph.D. ’72, an emeritus history professor at Duke University and former member of Harvard’s Board of Overseers, submitted this essay reflecting on the recent removal of the massive John C. Calhoun statue in Charleston, South Carolina—a timely contribution toward putting current events, controversies, and decisions into their long-simmering, historical context. ~The Editors

I first visited Charleston 50 years ago, as South Carolina celebrated the 300th anniversary of its birth in 1670. As a Harvard graduate student studying early American history, I hoped to write a dissertation on the beginnings of African enslavement in the colony, although my Ivy League mentors wondered if sufficient sources existed. While turning my research into a book, I fell in love with Charleston, except for one huge and forbidding public monument.

More than a century after black emancipation, a monstrous statue of John C. Calhoun still hovered over the old port city. Even after the Freedom Movement of the 1950s and ’60s, a leading mastermind of white supremacy retained a central place of honor, high above Marion Square. As I came to understand how deeply his defense of racial oligarchy was still rooted in the soil of the Lowcountry, I wondered if he would remain there forever.

Ever since Ozymandias named himself “King of Kings,” monuments have come and gone. In Biblical times, Samson pulled down the Philistine temple to Dagon, and in Reformation England, Protestant zealots decapitated figures of Catholic saints. In Revolutionary Manhattan, patriots toppled a statue of George III, melting it into musket balls for their independence struggle.

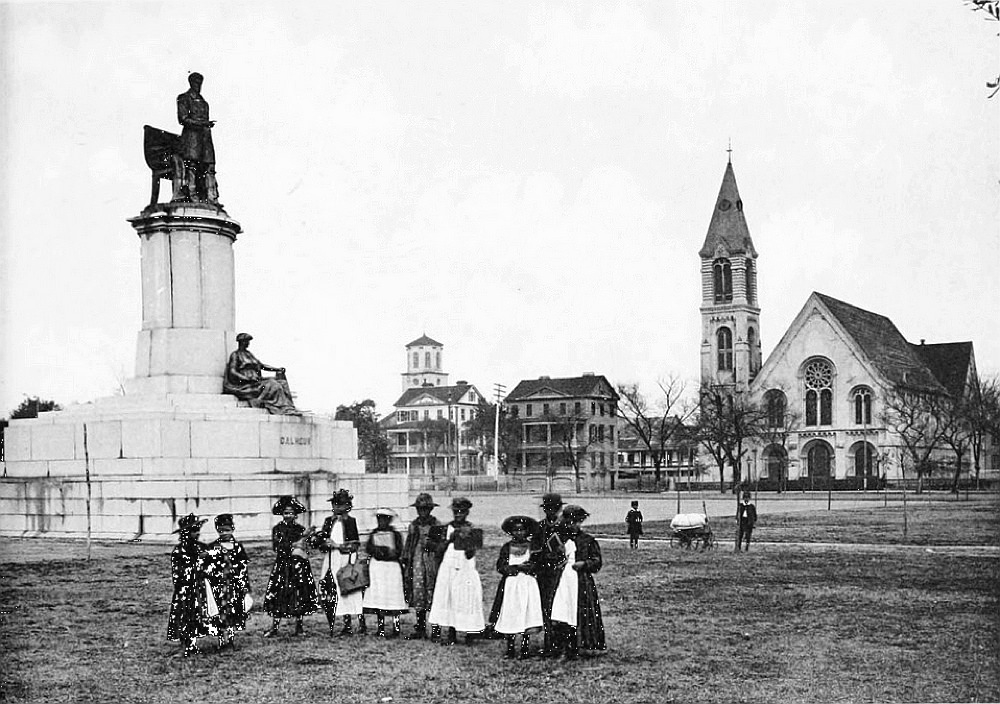

This monument to John C. Calhoun, dedicated in 1896, loomed over the center of Charleston, South Carolina for 124 years.

Photograph from the Library of Congress

And the beat goes on in our own century. In 2003, U.S. troops in Baghdad used an armored vehicle to haul down a statue of the Iraqi despot Saddam Hussein from its marble plinth. In 2014, Ukrainians toppled so many Russian-made statues of Lenin (376 in February alone) that the era is remembered as “Leninfall.”

That same year, Michael Brown, a black youth in Ferguson, Missouri, died at the hands of a white police officer. His death followed the murder of Trayvon Martin, a seventeen-year-old African American, in Florida in 2012 and the acquittal of his killer the next year, sparking creation of the Black Lives Matter Movement. Anguished responses to these events brought into sharper focus many similar deaths that had been routinely ignored or explained away.

The next year, 2015, a white supremacist massacred eight black parishioners and their pastor at Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. The young killer had taken selfies on local plantations and flaunted the Confederate flag. The murders he committed at Mother Emanuel, on June 17 took place scarcely two blocks from the lofty Calhoun monument. Ten days later, amid national grief and protests, a black student activist, Bree Newsome Bass, scaled a flagpole outside South Carolina’s State Capitol Building in Columbia and removed the Confederate battle flag. The beginnings of “Leefall” in the United States could not be far behind.

In February 2017, the Charlottesville City Council decided, by a 3-2 vote, to remove a towering monument in honor of General Robert E. Lee that had stood for a century. When Charlottesville’s equestrian statue was commissioned in 1917, Virginia-born Woodrow Wilson (whose name was also recently removed from Princeton’s public policy school) occupied the White House. The monument was dedicated in 1924, at the height of the Ku Klux Klan’s national resurgence. Word of its pending removal led white supremacists to rally in the university town in August 2017, resulting in the death of Heather Heyer and the injuring of 19 other people.

Much had changed since Woodrow Wilson’s time in office; a century later, voters put an African American family in the White House for two terms. The Black Lives Matter Movement was gaining strength, so Leefall continued, in the face of predictable resistance. In May 2017, a likeness of Lee was one of four Confederate statues removed in New Orleans. Mayor Mitch Landrieu explained that these memorials belonged to the terrorism of the Lost Cause “as much as a burning cross on someone’s lawn; they were erected purposefully to send a strong message to all who walked in their shadows about who was still in charge in this city.”

A new and integrated generation of students began to sharpen their questioning about General Lee. Wasn’t he a wealthy slaveholder who had renounced his military oath of allegiance at West Point to fight against the United States as part of a pro-slavery secession movement?

Landrieu quoted Alexander H. Stephens, who proclaimed in 1861 that the cornerstone of the South’s new Confederacy was “the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.” This long-ignored speech by the vice president of the Confederacy echoed Calhoun and prompted one modern historian to observe: “Stephens's prophecy of the Confederacy's future resembles nothing so much as Hitler's prophecies of the Thousand-Year Reich. Nor are their theories very different. Stephens, unlike Hitler, spoke only of one particular race as inferior."

Reading such pronouncements for the first time, a new and integrated generation of students began to sharpen their questioning about General Lee. Wasn’t he a wealthy slaveholder who had renounced his military oath of allegiance at West Point to fight against the United States as part of a pro-slavery secession movement? In August 2018, my own institution, Duke University, removed Lee’s statue from among the venerated historical figures placed at the entry to the university’s chapel in 1932.

But could Charleston ever see a Calhoun-Fall? It took the city’s white elite almost 50 years to raise their statue honoring the U.S senator and vice president who had defined race-based enslavement as representing God’s natural order and a “positive good” for all concerned. Born in upstate South Carolina in 1782, Calhoun died of tuberculosis in Washington, D.C., in 1850. Vessels in Charleston harbor lowered their flags when a ship returned his body to his home state, and the port city’s white minority went into mourning.

Church bells tolled, black crepe shrouded shop windows, and crowds lined the streets, wearing black armbands, as the senator was taken to his burial spot in St. Philip’s Churchyard. (The city’s black majority of 23,000 people shed few tears for the theoretician who had fostered the interests of his supposed master race and master class.) Four years after his death, local admirers organized the Ladies’ Calhoun Monument Association. The Charleston Mercury applauded their grandiose scheme for a soaring memorial as “chaste, yet elaborate.” “The design,” explains South Carolina historian Paul Starobin, “called for an edifice of about ninety-five feet in height. From the marble base, a flight of stairs would lead first to a set of four statues representing Liberty, Justice, Eloquence, and the Constitution, and then to a platform with a colonnade of Corinthian columns.” At the pinnacle would stand “an immense, twelve-foot-high statue of Calhoun with his right arm extended upward and his hand pointed toward heaven.”

Hopes high, the Monument Association laid the cornerstone on Carolina Day, June 28, 1858. The ladies made sure it contained a lock of the great orator’s hair and a copy of his last Senate speech—a tirade against any sectional compromise that might limit slavery’s continental expansion. But the Civil War halted work on the memorial, and during Reconstruction Charleston’s Marion Square (known as Citadel Square until 1882) became a contested space.

From 1865 until 1879, U.S. Army troops occupied the huge brick Citadel adjacent to the Square. (In 1822, in the aftermath of the Denmark Vesey slave revolt, the state legislature had authorized its construction to serve as an arsenal and guard house protecting white residents.) During Reconstruction, the new South Carolina National Guard, made up primarily of black South Carolinians, used the open field for drills and parades. Curious white onlookers watched the new game of baseball there, and African Americans gathered in the park for political rallies and civic celebrations.

With the end of Reconstruction, Lost Cause elites reasserted local dominance. After renaming and landscaping the central green, they commissioned a Philadelphia sculptor to create a statue to adorn a new Calhoun memorial there. Plans again called for the pedestal to be graced with four allegorical figures—this time females representing History, Justice, Truth, and the Constitution. Only one of these figures arrived in time for the dedication of the long-delayed monument in April 1887 before a crowd of 20,000.

When unveiled, there stood a larger-than-life representation of the orator, wagging his right index finger at all who passed. But this bronze reincarnation, atop a granite pedestal, lasted less than a decade. Standard accounts attribute the statue’s brief life to shortcomings in the sculptor’s awkward work, but black South Carolinians remember its demise differently. After all, when Boundary Street in front of Marion Square had been renamed Calhoun Street, they kept calling it Boundary, or they purposefully referred to it as Killhoun Street.

“As you passed by, here was Calhoun looking you in the face and telling you, ‘N—, you may not be a slave, but I am back to see you stay in your place.’”

Mamie Garvin Fields, born in Charleston in 1888, recalled that as a small black girl she often passed by the new Calhoun monument with her friends. “Our white city fathers wanted to keep what he stood for alive,” she recalled. So “they put up a life-size figure of John C. Calhoun preaching and stood it up on the Citadel Green, where it looked at you like another person in the park.” A photograph made in 1892 shows a group of neatly dressed black girls, posing respectfully near the granite base. But as Fields made clear, such school children sensed the statue’s true purpose.

This 1892 image by A. Wittemann appeared in Charleston, S.C. Illustrated. Four years later, the city’s Lost Cause elite replaced this memorial with a more presumptuous and far less accessible monument to Calhoun that stood until June 24, 2020.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Blacks took the statue personally,” Fields claimed in her powerful memoir, Lemon Swamp, explaining ways in which Calhoun, though long dead, had haunted her childhood. “As you passed by, here was Calhoun looking you in the face and telling you, ‘N—, you may not be a slave, but I am back to see you stay in your place.’”

Mamie and her friends “didn’t like it. We used to carry something with us, if we knew we would be passing that way, in order to deface that statue—scratch up the coat, break the watch chain, try to knock off the nose—because he looked like he was telling you there was a place for ‘n—s’ and ‘n—s’ must stay there.” According to Fields: “Children and adults beat up John C. Calhoun so badly that the whites had to come back and put him way up high, so we couldn’t get to him. That’s where he stands today,” she concluded, “on a tall pedestal. He is so far away now until you can hardly tell what he looks like.”

This apotheosis of Calhoun, elevating a new and even larger statue toward the heavens, was accomplished in 1896. The previous year, white citizens had adopted a new constitution that disenfranchised black Carolinians, and they had sent their notoriously racist governor, “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, to represent South Carolina in the U.S. Senate. “We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will,” Tillman proclaimed. “We have never believed him to be the equal of the white man, and we will not submit to his gratifying his lust on our wives and daughters without lynching him.”

Calhoun’s likeness still presided over central Charleston two years ago. With statues of Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis coming down across the region, we speculated when, if ever, this incongruous relic might disappear.

Spurred on by such racist demagoguery, well publicized mob violence continued across the state. In 1896, the documented lynchings of black men in South Carolina included Calvin Kennedy (Aiken, February 29), Abe Thomson (Spartanburg, March 1), Thomas Price (Kershaw, April 19); and Dan Dicks (Aiken, July 17). Revising Calhoun’s monument that year moved him above the reach of his detractors while still assuring that his glowering visage would dominate the urban landscape. He remained there when Mamie Fields died in 1987, at age 99.

Calhoun’s likeness still presided over central Charleston two years ago, when I joined a group of Colorado school teachers and students traveling to South Carolina to explore the roots of American racism. With statues of Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis coming down across the region, we speculated when, if ever, this incongruous relic might disappear. Several of the idealistic high school students from the West were dismayed to learn that local officials had only floated tepid proposals for placing an “explanatory” plaque at the column’s base, or erecting a smaller monument nearby for someone who opposed enslavement.

But after the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, the wind shifted dramatically. Suddenly the monument seemed even more offensive, an ever-present poke in the eye to local black residents and to distant visitors. When word spread that the Charleston City Council had voted unanimously to remove the domineering figure from his skyscraping column, I thought of a comment Walt Whitman recorded at the end of the Civil War. After Confederate forces had surrendered at Appomattox Court House, the poet overheard a Union soldier observe that the true monuments to Calhoun were the wasted farms and gaunt chimneys scattered over the South.

Most of those gaunt chimneys fell long ago, and once-wasted farms now grow soybeans or shoulder suburban sprawl. But the unreachable figure of Calhoun still dominated the Charleston skyline, even after the National Park Service, in 2016, turned back a formal request from an eminent civic group. The Charleston World Heritage Coalition had asked the NPS to nominate the city to the United Nations as a worthy site to be included on UNESCO’s official and prestigious World Heritage List.

The rejection sent a clear message to Charleston’s civic leaders about their aspirations to gain UN recognition for Charleston as a world heritage cultural center and to increase tourism with a new International African American Museum. How could these efforts succeed if the city continued to leave in place such a contradictory and outdated tribute to pro-slavery doctrine? So on June 24, 162 years after devoted ladies placed a lock of their hero’s hair in the first cornerstone, a 17-hour effort by city workers with cranes and welding torches brought the burdensome figure back to earth. The moment for Calhoun-Fall had finally arrived.