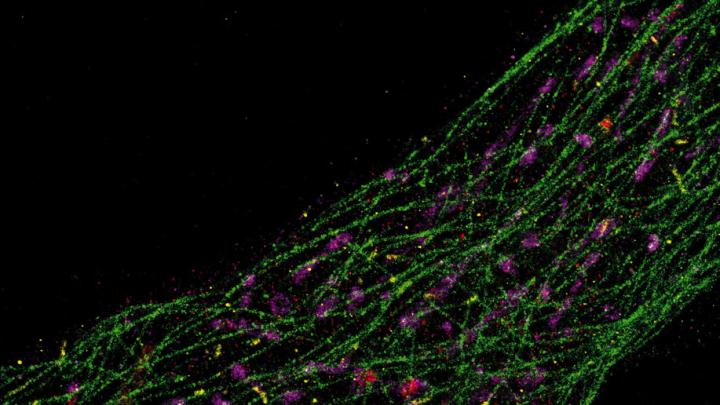

Nobody had ever seen what tiny structures inside cells actually looked like until Peng Yin used DNA to make this invisible world visible.

DNA is generally regarded as an information-carrying molecule that contains the instructions describing how to arrange amino acids to build proteins, the functional units that carry out life processes. But DNA is also a physical material that can be formed into useful objects, and manipulated to perform dynamic actions. Yin is a master builder and engineer of DNA at the molecular scale. A Harvard Medical School professor of systems biology affiliated with the Wyss Institute, he manipulates nanoscale biological parts to build useful objects such as probes that can detect even a single-base genetic change and imaging technologies with unparalleled resolution, brightness, and scope.

The end to which Yin has focused this expertise—the application of which he is most proud—is bioimaging of tissue samples for diagnostics and basic science research. In this arena, at atomic-level scales, he has used short fragments of DNA as “docking strands” that can capture introduced fluorescent compounds to enhance details in biological structure that would otherwise be invisible to even the best microscopes. Yin can implant DNA docking strands in a cell and program them to bind to a particular protein target. The docking strands, like kelp waving at the bottom of the ocean, await the passing fluorophores that have been injected into the cell. These they capture and release: a binding/unbinding action that causes the fluorophores to emit light. That transient immobilization of a fluorophore in the focal plane of the microscope—held for a moment by the DNA docks—enables complementary software to pinpoint the exact location of particular intracellular features. The resulting acutely sharp images offer resolution that can distinguish features just five nanometers across. This has important biological implications, Yin explains, because five nanometers is about the size of a small protein.

The tool he has developed will enable biology students to see tiny intracellular structures accurately for the first time, not as imagined in textbook illustrations. And because the tool has now been licensed to a company (Ultivue), the technique will help bioengineers and physicians in their research. “That gives [me] a great amount of satisfaction,” Yin says, “because you not only provide the paper, you actually have something people can use.”