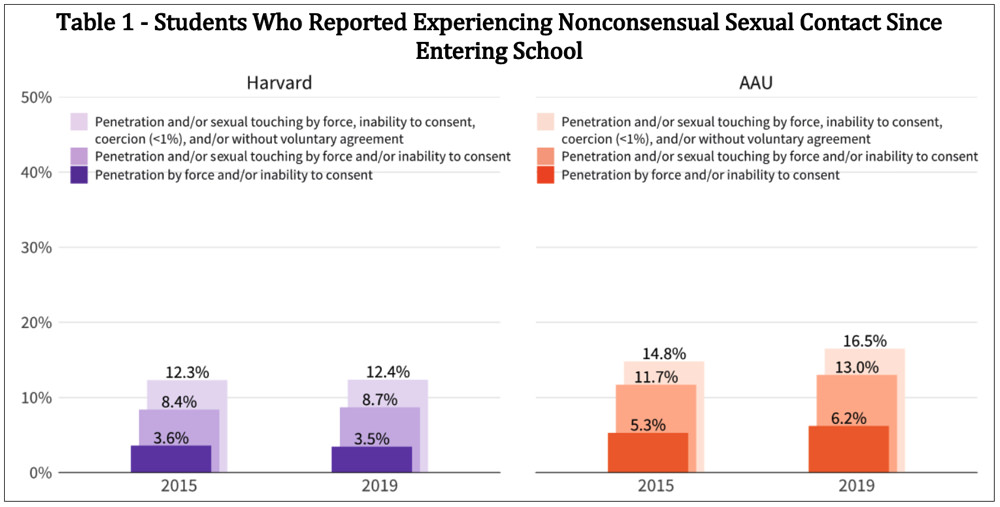

On October 15, Harvard released the results of a survey intended to estimate the prevalence of sexual assault and other sexual misconduct among its undergraduate, graduate, and professional-school students. The survey, conducted during the spring of 2019, reached about 23,000 students, of whom 36.1 percent (about 8,300) responded. The data—echoing those from the 32 other private and public Association of American Universities (AAU) institutions that participated in this year’s survey— show that sexual assault and harassment are a serious problem. At Harvard, the prevalence of sexual assault (12.4 percent) was essentially unchanged since a similar survey was conducted in 2015.

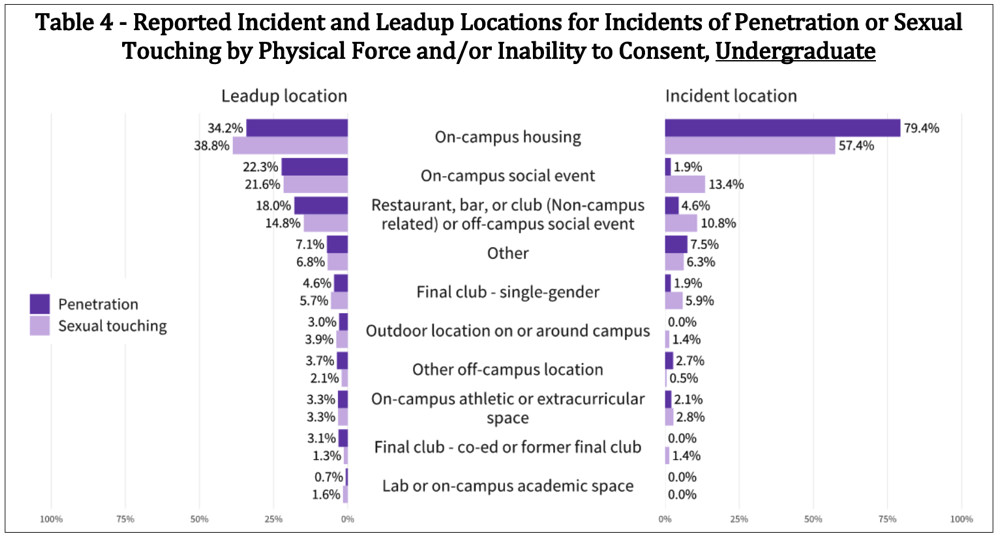

Among undergraduates, the vast majority of nonconsensual sexual contact is student to student (82.5 percent), takes place in on-campus housing (more than two-thirds overall, and 79.4 percent in incidents of penetration or sexual touching by physical force and/or inability to consent), and involves alcohol (75.6 percent). Rates among graduate students, who are less likely to live in on-campus housing, less likely to go out drinking with friends, and less likely to be single, are lower, but on-campus housing remains the modal location for sexual assault. Although the rates at which students disclose these incidents have been climbing rapidly (the rate of disclosure increased 56 percent in fiscal year 2018) the majority of students do not disclose incidents to the University, the survey showed—and the prevalence of nonconsensual sexual contact has been unaffected by rising disclosure rates. Among all AAU institutions that participated in both the 2015 and 2019 surveys, the prevalence of nonconsensual sexual contact has risen slightly overall.

Chart from the Harvard AAU steering committee letter to President Bacow

The most significant change to the 2019 survey is that it introduces “incident level reporting” for cases of both sexual assault and sexual harassment: students who indicate that they have been victims of sexual assault, for example, are asked a series of additional questions, such as the nature of their relationship to the perpetrator, where they were during the time leading up to the incident, where they were when the incident occurred, the perpetrator’s relationship to the University, and whether they contacted any of the resources or support services available to them on campus (see table 4, above). With incident level reporting, the assertion made based on 2015 data that among undergraduates “about 15 percent of incidents took place in single-sex organizations that were not a fraternity or sorority”—final clubs—appears incorrect. Among Harvard College students, “on-campus social events” and “restaurants, bars and clubs” figure more prominently in both “leadup location” and “incident location,” behind on-campus housing.

Questions about sexual harassment, as opposed to assault, were changed in the 2019 survey, meaning that the data can’t be reliably compared to the data from the 2015. Harassment, however, remains a serious concern: 39.3 percent of respondents reported experiencing harassing behavior, and 17.7 percent reported that the harassment interfered with their academic or professional performance, limited their ability to participate in an academic program, or created an intimidating, hostile, or offensive social, academic, or work environment. As with allegations of assault, most harassment was perpetrated by other students.

Since the 2015 survey, Harvard has expanded its support services and educational outreach to its student communities. In 2016, the University hired Nicole Merhill as its Title IX officer, and specified that she spend 50 percent of her time designing prevention initiatives. Since then, 65,000 students, staff, and faculty members have participated in online training, and in-person training has been increasing rapidly, too (by 41 percent in the past year). Merhill has created two Title IX liaison groups, one for students and another for staff. And she has made a number of changes designed to increase the likelihood that students will disclose incidents of assault and harassment to University administrators, including expansion of its system of more than 50 Title IX coordinators. “Bystander” training, another initiative, seeks to increase the likelihood that students, faculty and staff will intervene if they see behavior that presages sexual assault. Most recently, Merhill established an online anonymous disclosure tool in response to student concerns that reporting an incident might lead to their losing control over the ensuing process. The new tool is designed to allow University affiliates to communicate with the University Title IX Office without revealing their identity until they are ready.

Nevertheless, most students who reported an incident of sexual assault did NOT seek out aid, whether from University Health Services, the office of BGLTQ student life, the mental-health counselors, the Title IX office, the Office for Dispute Resolution, the office of sexual assault prevention and response, Harvard chaplains, or student peer supports. The principal reason students gave for not reporting an incident was that it wasn’t serious enough. However, a majority reported that they did speak with friends and family about the event.

Overall, the prevalence of nonconsensual sexual contact is lower at Harvard than at peer AAU institutions participating in the survey.

Chart from the Harvard AAU steering committee letter to President Bacow

In written recommendations to President Lawrence S. Bacow, deputy provost Peggy Newell and Cahners-Rabb professor of business administration Kathleen L. McGinn, co-chairs of the Harvard 2019 AAU Student Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct, wrote that:

Knowledge of support services and belief in the fairness of University processes for investigating reports of nonconsensual sexual contact and sexual harassment have both risen since 2015, but less than half of our students feel very or extremely knowledgeable about support services on campus and less than half of our students believe that the outcome of University processes related to reports of sexual misconduct will be fair.

In spite of heightened attention to nonconsensual sexual contact and sexual harassment in society, in the media, and at Harvard, only a minority of students experiencing nonconsensual sexual contact or sexual harassment access any of the resources available on campus….

The steady and high rate of nonconsensual sexual contact experienced by Harvard students calls for a cultural change across our community.

President Bacow, in a letter to the Harvard community, wrote that:

the data support the reality that sexual assault and sexual harassment remain a serious problem at Harvard, and at institutions of higher education across the country….We must do more to prevent sexual and gender-based harassment and assault, and to encourage people to come forward to share their experiences and their concerns with us. And we must not rest until every member of our community has confidence in their institution’s ability to support them. This responsibility starts with the University leadership, but we can only truly effect meaningful change with your ideas and your commitment….

“Initiatives like bystander training,” he continued, “send the message to students that sexual misconduct is not acceptable." He has therefore “asked the Title IX Office to oversee the expansion of more of these bystander intervention initiatives across the University.” But he noted that “A change in culture can only come about through shared efforts by the administration, faculty, staff, and students,” and he invited all members of the Harvard community to a conversation about the issues raised by the survey at the Science Center on October 17.

“One of my highest priorities,” he concluded, “is to create a community in which all of us can do our best work. To achieve this, we must seek to enhance our policies and procedures, and build out new resources, that are marked by our humanity, and which remind us to care for one another. But most importantly, we must recognize that we all have a role to play in ensuring that each of us who calls Harvard home feels welcome, and safe.”