What role do educators have in changing and shaping the cultural attitudes and social practices that still—consciously and subconsciously—reinforce what W.E.B. Du Bois, most famously, called the color line?

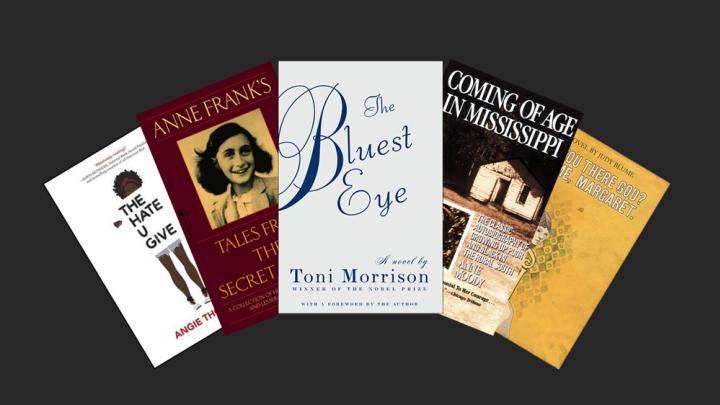

Reading Toni Morrison's God Help The Child recently, as part of a faculty seminar and presentation, got me thinking about my own literary journey and this very question. I was struck by the fact that the central theme of colorism and racism found in God Help the Child, written in 2015, had not changed much from the theme of colorism explored in The Bluest Eye, even though these books were written almost half a century apart. This observation caused a robust, revealing, and enlightening discussion in our seminar of educators and university professors, the type of discussion that underscores again why diverse literature is important.

From kindergarten to college and through law school (from the 1970s to the 1990s), only once was I assigned a black female author as part of my formal studies. I was an avid reader and book lover from an early age, taking regular trips to the original Barnes and Noble store on Fifth Avenue and 17th Street with my dad to buy books. In kindergarten and first grade, my absolute favorite book and author of all time was Beverly Cleary. I read everything she wrote and I loved loved loved the Ramona the Pest book and series, and saw myself in Ramona—the Haitian-American version, that is. In elementary school, the books I chose to read also included everything by Laura Ingalls Wilder, the Nancy Drew books, and Anne Frank’s Diary (which opened up a life-long interest in Holocaust memoirs and literature). But by middle school, it was all about the young-adult iconic authors: Judy Blume, Norma Klein, Paula Danziger, and others. My friends and I related to Margaret in Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret and to the other characters in those popular books because they explored universal young-adult themes. It never occurred to me that I was missing a black protagonist (or black female author) in the books that I read for pleasure or for school.

But then, around sixth grade, I read Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye on my own. It’s only in retrospect that I can truly appreciate the impact this book had on me. Something about the issues of color and race must have resonated; something also about Pecola being black, and the author being black, resonated too. The Bluest Eye was my gateway book—the book that opened a whole new literary journey and genres for me and led to my joyfully discovering and devouring other black female writers during high school—Rosa Guy, Paule Marshall, Alice Walker, Maya Angelou, Nella Larsen, Zora Neale Hurston, Ntozake Shange—none of whom I have ever read for a class or in an academic setting, including in my high-school honors English and AP classes in the 1980s, where we did not read a single woman of color. I was in college in 1988 when 48 prominent black writers (male and female) felt compelled to issue a statement (published in The New York Times) in praise of Toni Morrison’s work and deploring the fact that she had not won a National Book Award or the Pulitzer Prize, and referencing The Bluest Eye, where Morrison “demanded our public and private confrontation with the power of her work,” including her depiction of “the unbearable self-loathing of one black child, Pecola Breedlove, who could not escape America.”

When I asked my cousin, Marie-Alyse, about her related experiences in high school and college, she quickly texted back:

In high school, I read Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, and Maxine Hong Kingston’s Woman Warrior, and Toni Morrison on my own. They blew me away! In fact, you were the one who had mentioned Toni Morrison and Alexis Deveaux to me back in high school. College was no different. I had to read Soyinka on my own and he had won the Nobel Prize! At Barnard I had an argument with my professor about this very thing. I took Modern Drama. There were 100 books on the reading list. Not one woman or man of color. My professor told me he didn’t want to put one on the list just to do it; that the rigorous writing, like Ibsen’s, “just wasn’t there.” I will never forget it. I dropped that class soon after.

But I had one professor in college, Dr. Miriam Frank, an American of German descent, who included Anne Moody’s memoir, Coming of Age in Mississippi, on a humanities syllabus that included Goethe, Schiller, Ibsen, and Virginia Woolf. When I contacted Professor Frank recently to ask about what I thought, then and now, was a radical act, she told me: “I assigned it because it is a great book. It’s the story of the Civil Rights movement; it’s a coming-of-age story where she struggles with her family, with finding a place in the larger world, with having a larger purpose. When I started teaching college, I taught at a community college in Detroit where I was the only white person in the room. In Detroit at the time, poet Dudley Randall had a press and was publishing black authors. I got my hands on Audre Lourde’s chapbooks and I started diving into what black women were writing. At the time there were no anthologies of black women writers. I included that book, and others, on my syllabus because it was the right thing to do.”

That I never had the benefit or privilege of reading any other black female authors in an academic class from elementary school to graduate school did not lesson their impact on me. Reading them on my own gave me some freedom in reading them for joy and pure pleasure, not for a grade or requirement. But the downside was that these authors were not being read in a setting where important social issues (including colorism, racism, and the pigmentocracy) could be debated, challenged, and explored with a cross section of peers as part of our collective educations. This is where educators—college professors, K-12 teachers, parents—can use literature to help change entrenched cultural and social attitudes that have tragic consequences on lives.

The situation has improved since the 1980s. As a young lawyer in the late 1990s, I was hired to help write Law School Admissions Test questions so that they reflected more diverse and inclusive subjects. And the AP Literature exam now includes questions covering black female writers (Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Paule Marshall, Nella Larsen, and others), as well as diverse writers, both male and female, representing China, Japan, Afghanistan, Nigeria, Haiti, India, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and Trinidad. Universities are developing inclusive pedagogy, faculty seminars, and programs aimed at widening the canon and curriculum. And writers and publishers are expanding the narratives about the stories we think we know in any number of fields, from math and science to the arts and more. Think of the best-selling books Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race and The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, about the black woman whose unique cells helped advance medical research; or this year’s “Posing Modernity” exhibition, at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery and the Musée D’Orsay, about long-ignored black models in works of art from Manet to Matisse to today. Similarly, recently historians, museum educators, and curators of historic antebellum plantation homes have started to expand the lens and framework through which these homes and their stories are typically shown and presented (with a focus on architecture, furniture, and property owners) to include previously omitted and ignored facts and artifacts about the slave labor and slave economy that helped build them, and the slave cabins and enslaved people that coexisted with them.

My daughter is 12. Last fall her seventh-grade class read Angie Davis’s best-selling young adult novel, The Hate U Give, about race, class, and police brutality: a book written by a 29-year-old black female writer, featuring a black female protagonist, assigned by her biracial Haitian-Jewish English teacher, that was discussed by a diverse group of pre-teens who are friends and spend eight or more hours a day together. That has to mean something. I was happy for her; this was progress as compared to my own experience.

However, I won’t lie. Part of me (probably for nostalgic reasons and because of the enduring impact these beloved classics have had on me and so many others) would have preferred that they read The Bluest Eye or The Diary of Anne Frank, because I have diligently tried for the past year to get her to read Edwidge Danticat’s Breath, Eyes, Memory, and Rosa Guy’s The Friends and she has not shown any interest. She prefers Michael Crichton, Stephen King, the Percy Jackson series, Harry Potter, anything with adventure, science fiction, Greek mythology.

I asked her what she thought about reading The Hate U Give for class. She said that while she enjoyed the book, “I didn’t really enjoy reading it with the class. The book is for a certain kind of audience and my seventh-grade class was not that audience.” She felt that the weighty topic of police brutality was too heavy for her class and that most students read the book because they had to get a good grade, and they did not seem to fully engage with the big ideas of the book. She thought maybe the themes were too advanced for their grade.

I was surprised to hear this, given that other seventh-grade books from my era, such as The Outsiders, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, and To Kill A Mockingbird also address similarly weighty topics. However, on balance I still think it is important and a wonderful change that her teacher assigned this book and that the class got to discuss and debate it together, because in the twenty-first century we are still grappling with what Du Bois called a twentieth-century problem.