At a time when the United States is preoccupied with its relations with virtually everyone else in the world, it is worth being reminded that other nations have their own relationships with one another. As Ezra Vogel, Ford professor of the social sciences emeritus, so brilliantly argues in his latest book, China and Japan: Facing History, probably no other bilateral relationship comes close to combining the mixture of profound cultural affinity, intense national rivalry, and long-term geopolitical import found in that between China and Japan. Given his unparalleled knowledge of the language, culture, and society of both nations, Vogel is uniquely positioned to tell this story. He is, after all, one of the few scholars ever to have written pioneering books about each society—Japan as Number One: Lessons for America (1979) and Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (2013)—that also achieved best-seller status within each society. With China and Japan: Facing History, Vogel now turns to the interaction between these two great societies.

As the book makes clear, Japan and China for more than 1,500 years have shared bonds of deep cultural interconnection and mutual learning. At the height of premodern cosmopolitanism during the Tang Dynasty (618-906 c.e.), Buddhism, Confucianism, and written language (Chinese pictographs) all made their way from China to Japan. The vector was neither war nor conquest, but instead a small number of individuals in the cultural sphere: Japanese monks who had studied in Chang’an, the great Tang capital at the eastern end of the Silk Road; Koreans situated geographically between the two great cultures and accustomed to navigating both; and a select few Chinese monks and craftspeople who had made their way to Japan.

A thousand years later, during the May 4th Movement (1919), the great intellectual burgeoning considered by many Chinese to be their nation’s first modern moment, the flow of ideas would persist, albeit in the reverse direction. So many of the era’s leading lights—including the writer Lu Xun and two of the co-founders of the Chinese Communist Party, Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao—all spent key formative years in Japan. It was there that they witnessed Meiji-era Japan’s standing up to the West, thanks to a strong state, a powerful military, and a citizenry galvanized by nationalism. While in Japan they were also able to be inspired by a Japanese society far more liberal, vibrant, and open to ideas—including many from the West—than anything comparable back in China.

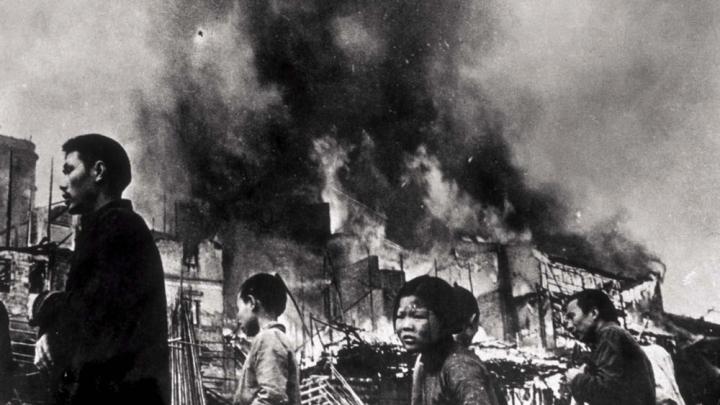

If only cultural cross-pollination described the totality of the Sino-Japanese experience. But as Vogel’s book painstakingly describes, the two nations are just as inextricably linked through calamitous violence, bloodshed, and subjugation. Bookended by the years 1895 and 1945, each society through its interaction with the other suffered devastating civilizational defeat.

Loss came first to the Chinese, who in their stunning defeat by Japan in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 would suffer not only the indignity of territorial loss—the ceding of Taiwan to the growing Japanese empire—but more existentially, the total collapse of their age-old system of domestic governance and social control. Within 20 years of the 1895 defeat, the last Chinese emperor had abdicated, Confucian society lay in shambles, and the country had split apart into warlord-run fiefdoms.

Into the breach surged an increasingly militarized and imperially ambitious Japan, first colonizing Taiwan and Korea in 1895 and 1905 respectively, then establishing a vassal state in Manchuria in 1931, and finally invading and occupying all of coastal China in 1937. The ensuing eight years of war would cost China roughly three million soldiers and 18 million civilians killed, and perhaps 100 million people displaced.

In 1945, having expended so much blood and treasure in its attempted subjugation of China, Japan would meet its own devastating defeat. Nobody, least of all Vogel, suggests a moral equivalence between Chinese and Japanese losses during this period, but again, the human toll is jaw-dropping. It is estimated that more than three million Japanese died during what in effect was the second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45). Almost a million of those casualties were civilians.

A Japanese print by Suzuki Kwasson depicting a Chinese defeat during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95)—one of the wounds dividing the neighbor nations

Image from Bridgeman Images

Yet as Vogel points out in an invaluable chapter on Japan’s colonization of Taiwan and Manchuria, this period of subjugation was about more than just violence and destruction. Indeed, it generated its own peculiar forms of inter-societal connectedness. Manchuria in the first decades of the twentieth century became in the Japanese consciousness what the “Wild West” had become in the American imagination a century earlier, a place to escape the constraints of home and begin life afresh. By 1937, roughly 270,000 Japanese farmers had settled in Manchuria. Still more Japanese populated the colony’s administrative offices, businesses, and extensive railway operation. By 1940, roughly 850,000 Japanese were living in Manchuria, meaning that families throughout Japan even today need not trace far back in history to find direct and highly personal links to China. Vogel notes the fairly typical example of Boston Symphony Orchestra director Seiji Ozawa, D. Mus. ’00, who was born in Shenyang in 1935, and spent the first nine years of his life in Manchuria.

The Chinese, too, found ways to adapt and interrelate as they navigated life under Japanese rule. In Taiwan, the best local students were sent to universities in Japan, preparation for subsequent careers in Japanese-run businesses or in the colonial administration itself. Indeed, as Vogel points out, locally born Taiwanese administrators—ethnic Chinese—were sent to Manchuria to help set up the Japanese colonial government there, and subsequently, to support the wider Japanese occupation after 1937. During the war years, numerous Chinese men in both Taiwan and Manchuria ended up serving in the Japanese armed forces. Lee Teng-hui, president of the Republic of China on Taiwan (and chairman of the ruling Kuomintang Party) from 1988 to 2000, served in his young adulthood as a second lieutenant in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. Lee’s father had been an administrator in the Japanese colonial police force on Taiwan, and his brother died in the service of the Imperial Japanese Navy during the war.

While Vogel appropriately resists judging these experiences, he performs great scholarly service in simply reporting them. Considered embarrassing or even scandalous by constituencies on both sides of the Japan-China divide today, these experiences have largely been erased from the historical narratives of both nations. The silence, however, underscores the sensitivity of the feelings involved, the depth of the psychic wounds, and the degree to which so much of this shared history remains unresolved.

The history of rivalry, particularly the trauma of the period from 1895 to 1945, continues to cast a long shadow over Sino-Japanese relations today. The two nations remain locked in a territorial dispute over islands in the Sea of Japan (East China Sea). Many Chinese today resent what they feel is Japan’s unwillingness to acknowledge, let alone take full responsibility for, atrocities committed against Chinese citizens during World War II. Many Japanese resent what they feel is the Chinese government’s encouragement of anti-Japanese xenophobia, and they fear China’s growing military might. In turn, many Chinese now accuse Japan of remilitarizing. The cycle of enmity persists.

Vogel’s work acknowledges all of this, and goes a long way to explaining it. But there is an equally important theme running through much of China and Japan: Facing History. Both nations—Japan since the middle of the nineteenth century, and China since the beginning of the twentieth—have been engaged in a self-aware and society-wide process of modernization. For both nations, this in essence has involved responding to an existentially challenging model posed by the West: the triumvirate of a strong state capable of projecting power, a strong nation galvanized by a common identity, and a strong industrial system energized by the Promethean power of state-of-the-art technology.

By virtually any measure—wealth, power, prosperity—Japan and China by the twenty-first century had navigated their way to success. For all the trauma experienced along the way, they had done so time and again by engaging in what Vogel in earlier works has termed a “group-directed quest for knowledge.” Both nations have demonstrated—and continue to demonstrate—a sublime capacity for society-wide learning, most often from practices observed abroad. What is more, they translate such learning into purposive and highly aspirational efforts at society-wide renewal, redefinition, and re-creation. From our own defensive crouch in the present era of “Making America Great Again,” we could do worse than open ourselves up to gleaning lessons from such an approach.