Late into the last evening of a sprawling two-day conference on art and race and culture and citizenship—and on the possibility of achieving justice—artist Hank Willis Thomas turned to the crowd in Sanders Theatre and sort of chuckled. His brain, he said, was “thick with ideas,” which he was clearly still working to absorb, and he thanked the audience for sharing the moment with him—by which he meant the whole long, thrilling, strenuous, powerful, time-dilated thing. Then, after a second’s hesitation, he asked everyone assembled to turn to the nearest stranger and give the same thanks, and for a moment, Memorial Hall was full of churchgoers in pews, speaking to their neighbors.

Willis Thomas wasn’t wrong: last week’s Radcliffe Institute event, Vision and Justice: A Creative Convening—which drew hundreds to Radcliffe’s Knafel Center and Sanders Theatre, plus nearly 2,500 viewers online—was as overwhelming as its organizers intended. Partly that was sheer volume: roughly 15 hours, altogether, of performances, videos, photographs, panel discussions, and talks. And partly it was star power. There was filmmaker Ava DuVernay, of Selma, A Wrinkle in Time, and 13th, on stage with Fletcher University Professor and PBS documentarian Henry Louis Gates Jr., talking about her forthcoming project, a miniseries on the Central Park Five. She had been introduced by film executive Franklin Leonard ’00, of Black List fame. And there was Chelsea Clinton interviewing author and pediatrician Mona Hanna-Attisha about the Flint water crisis. And New Yorker writer Jelani Cobb discussing the intertwined American histories of citizenship and racial narratives. Jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, Ar.D. ’09, gave a breezy, kinetic performance with three bandmates at 9 a.m., before sitting down to discuss cultural citizenship—and to share a funny story about Benny Goodman—with Harvard president emerita Drew Faust and director of the American Repertory Theater Diane Paulus. Poet Elizabeth Alexander, RI ’08, was in the lineup, too, along with author Claudia Rankine, artist Carrie Mae Weems, rapper Swizz Beatz (Kasseem Dean), and civil rights lawyer Bryan Stevenson, J.D.-M.P.A.’85, LL.D. ’15.

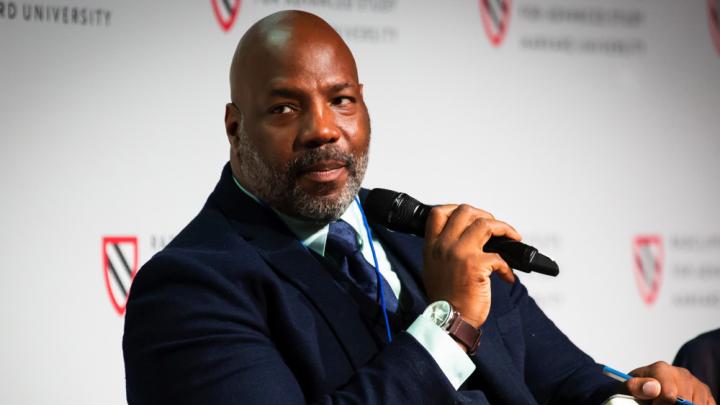

Stevenson, whose Equal Justice Initiative last year unveiled a national memorial honoring victims of lynching, gave the closing keynote and, in a panel earlier in the day, made a bit of news by adding his support to the Harvard Prison Divestment Campaign, a campus activist effort pushing Harvard’s administration to divest from holdings related to the prison industry (the campaigners have protested publicly in recent months at events featuring President Lawrence S. Bacow). “I don’t have any space for defending or justifying or rationalizing investing in prisons,” Stevenson said during a conversation about mass incarceration with Danielle Allen, Conant University Professor and director of the Safra Center for Ethics, and Elizabeth Hinton, associate professor of history and of African and African American studies. Stevenson went on: “We talk about veritas at this university. … I think the question is, are we going to lead? Does ‘truth’ mean leadership? Does veritas mean leadership? I think it does.”

But there was also a deeper thread of meaning and emotion permeating the event, which examined how black artistic culture, especially the visual arts, have always insisted on African Americans’ humanity and belonging, even as racism’s “ocean of images,” as Lawrence Bobo, Du Bois professor of the social sciences, put it, has worked to denigrate African Americans’ humanity.

That deeper thread had to do with history and memory and the legacy of black creativity stretching back generations. Again and again, speakers invoked figures like Langston Hughes, Frederick Douglass, and Spike Lee. The program was studded with tributes to artistic elders: photographers Deborah Willis, Dawoud Bey, the late Gordon Parks (whose artwork is on display at the Hutchins Center, in one of three exhibits associated with the conference), and Jamel Shabazz (“the proud belonging to each other—communal, disciplined, active—hardly a people defined by deprivation and deficit,” Kennedy School professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad noted in his remarks about Shabazz’s photographic subjects). More than one speaker seemed suddenly moved, taking in the enormity of it all: the vast body of work represented by the artists and scholars present at the conference, and beyond that, the whole history, impossibly more vast and lush, of art and narrative created by black Americans going back to the era of enslavement. As DuVernay said at one point to Gates, “The truth is, we have always told these stories.”

The conference and the ideas behind it were the work of Sarah Lewis ’01, assistant professor of history of art and architecture and of African and African American studies, who opened the proceedings with the question that has animated her own research: “What is the role of art for justice?” Later, she told the story of Charles Black, a white lawyer who first became persuaded that segregation must be wrong when he heard Louis Armstrong play at an Austin hotel one night when he was 16 years old and recognized in him “a kind of genius.” Twenty-three years later, Black helped win Brown v. Board of Education. “The work of culture alters our perceptions,” Lewis said. “It connects us to the work of justice. How many movements have begun when a work of art, when culture, so shifted our perceptions of the world entirely that we had to conceive it anew? I think more times than we can possibly imagine.”

Something like that happened to Lewis during her dissertation research not quite a decade ago, when she ran across an obscure speech by Frederick Douglass, “Pictures and Progress,” delivered in Boston’s Tremont Temple in 1861. He spoke of photographs as “thought pictures” with the power to “body forth in living forms and colors the ever varying lights and shadows of the soul.” Image-making, he knew, could define, or redefine, perception.

Out of that framework, Lewis has developed several projects bearing the “Vision and Justice” name: a Harvard course, which quickly became part of its General Education program, an exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums, and a 2016 issue of Aperture magazine, which Lewis guest-edited, publishing essays on the role of photography in African-American life. It became Aperture’s best-selling issue.

The conference offered perhaps the widest-ranging interpretation yet of the Vision and Justice concept. Weems performed selections from her multimedia piece, “Grace Notes: Reflections for Now,” grieving and grappling with the deaths of young African Americans lost to police brutality. Artist and journalist Alexandra Bell discussed her “Counternarratives” series, which interrogates how news media and conventional reportage spread racist ideas. Bell annotates news stories, primarily from The New York Times, redesigns front pages, and sometimes rewrites headlines, printing out enlarged versions of her alterations (perhaps her most well-known work critiqued the coverage of Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri). “The ‘Counternarratives’ series is something I first thought of sitting in a classroom with mostly white people, trying to figure out why the news felt like it was giving me the facts, but it wasn’t the truth,” Bell said.

Architect David Adjaye, who designed the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, as well as Harvard’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, described growing up in London as an immigrant from Tanzania, and feeling like a conspicuous outsider to the built environment around him. “Architecture is very silent but strong story-making,” he said. “It is a stage on which we all perform. And what we don’t realize is, that stage actually choreographs how we belong.” Computer scientist Joy Buolamwini, who participated in a panel discussion on algorithmic bias with professor of government and technology in residence Latanya Sweeney, also performed a spoken word poem, “AI, Ain’t I a Woman?” as images flashed behind her showing facial recognition software repeatedly mislabeling black women—from Sojourner Truth to Serena Williams to Michelle Obama—as men.

Installation artist Theaster Gates, whose Rebuild Foundation turns urban-redevelopment projects into a form of artwork, transforming abandoned buildings on the Chicago’s South Side into strikingly beautiful spaces for cultural organizations and affordable housing, spoke about how the physical surroundings in poor neighborhoods often reinforce layers of poverty, both material and spiritual. “When I look at the landscape of the South Side of Chicago, or spend time in Gary, Indiana, or Akron, Ohio, and I look at a main street there—I mean, when you look at the violence people talk about…I have to ask myself, have we created the preconditions that allow young people to be just? If the only space that you have is a strip mall that has a Pizza Hut, a laundromat, and a Walgreen’s, and no one has a job—is it possible that within that architectural sphere, is there space for us to be our best selves?…When we’re designing space in our cities, I doubt if a commitment to memory and dignity is part of the call for general contractors.”

With Adjaye sitting next to him, Gates contrasted that grim landscape with a building like the National Museum of African American History and Culture, with its inverted-pyramid tiers and bronze-filigreed façade. “I remember the first time I went to see your building in D.C.,” Gates said. “And there were school buses and charter vehicles, and people’s family reunions were happening at the Smithsonian. They were coming to see blackness. You could just stand in line and watch people witness the architectural image. And you could see that they were their best selves. … You could hear it over and over again: ‘I’m so glad to be here, I’m so glad to be here.’”

Adjaye said that he understood when he embarked on the project that it was more than a museum or a building. “It was a memorial, and it was also a shrine. And a shrine, you don’t need to go inside. A shrine requires just that you go near it.”

As the conference wound toward its final episode, the rousing keynote from Stevenson that would stretch past 10 p.m. and bring the audience to tears and then to its feet, the poet Elizabeth Alexander stepped to the podium to give what she called a “fulsome, church-style” introduction. But it was a rousing speech in its own right. “Our work embodies our ancestors’ wildest dreams,” she began. She meditated on the word “vision” and the word “faith”—“the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen”—and the concept of mercy. She talked about storytelling as a weapon, “making visible our wretched history of racial violence, whose implications lead us to today.”

She recounted a trip with colleagues last year to Angola Prison in Louisiana and detailed what she’d seen there: “black men filling cotton sacks under the guard of white men on horseback,” a hospice for elderly prisoners incarcerated since their teens, the rolling greens of a nearby golf course that advertises views of the infamous prison, with tee markers in the shape of tiny white handcuffs. She recalled a visit to a “compassion group” where for six weeks inmates practice creative writing and meditation, trying to gain “understanding of why people have pain, who they are, learning to be reflective.” She described the stunning sentence that one of the men in that group spoke that stopped her cold: “He said, ‘We dress our ideas in clothes to make the abstract visible.’ … What is the thin line that separates the young men I have taught from these young men? I would have been drawn into the circle if any student spoke those words.”

She read three poems: first, Gwendolyn Brooks’s “The Boy Died in My Alley,” then Lucille Clifton’s “The Photograph: A Lynching,” and then finally Robert Hayden’s “Frederick Douglass,” published in 1966, the finest American sonnet ever written, she said. Part of it reads like this:

…this man, this Douglass, this former slave, this Negro

beaten to his knees, exiled, visioning a world

where none is lonely, none hunted, alien,

this man, superb in love and logic, this man

shall be remembered.

Alexander let the poem’s words wash into the audience for a moment, and then she spoke again, repeating Hayden’s words slowly. “‘Visioning a world where none is lonely, none hunted, alien.’ Imagine that.

“If we can vision it, then we can work for it.”