It is among the highest-profile graduation-season speaking assignments on offer, a forum so freighted with potential that, as J. K. Rowling put it in her socko 2008 version:

Not only has Harvard given me an extraordinary honour, but the weeks of fear and nausea I have endured at the thought of giving this commencement address have made me lose weight. A win-win situation! Now all I have to do is take deep breaths, squint at the red banners and convince myself that I am at the world's largest Gryffindor reunion.

One need not go to the laborious trouble of becoming a global publishing sensation to land the assignment, however. A review of Harvard’s history reveals that perhaps the surest path to the podium is occupying a high government office in Germany. As The Harvard Gazette noted in announcing last December that chancellor Angela Merkel would be the speaker on the afternoon of May 30 this year, “Three German chancellors have delivered the address: Helmut Kohl, in 1990; Helmut Schmidt, in 1979; and Konrad Adenauer, in 1955. German President Richard von Weizsäcker was the speaker in 1987.”

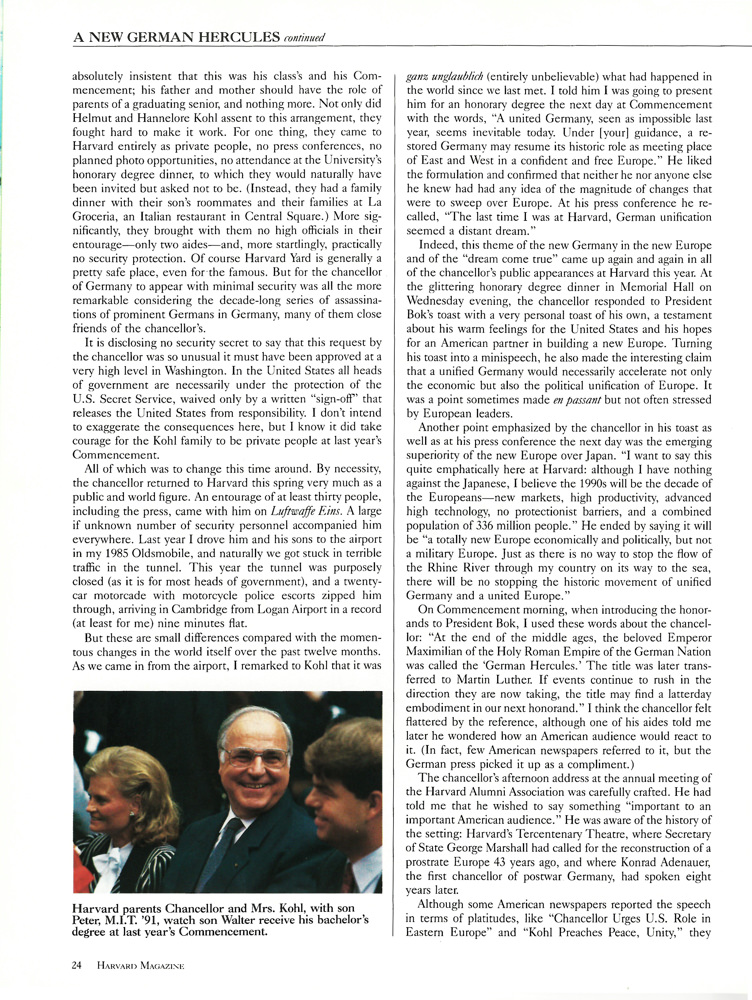

In fact, noted then-University Marshal Richard M. Hunt in an affectionate July-August 1990 Harvard Magazine profile of Kohl, “except for [Kurt-Georg] Kiesinger, a less well-known figure, Harvard Commencement speakers have included every postwar German chancellor, from Adenauer to Erhard to Brandt (actually governing mayor of Berlin at the time, soon to be chancellor) to Schmidt. Moreover, it’s true that the relationship between Germany and Harvard is a strong one,” dating to the nineteenth-century import of German standards of scholarship and education; the collection of twentieth-century German art; and the welcoming of scholars fleeing Hitler in the 1920s and 1930s (see “The Grand Wake for Harvard Indifference,” by Gerhard Sonnert and Gerald Holton, September-October 2006, and this report about the reinstalling a plaque in Harvard Yard honoring students who helped refugees escape Nazism in the 1930s). Kohl’s family also made a determinedly private appearance at the 1989 Commencement, when son Walter Kohl received his A.B. In the intervening year, the USSR cracked open and, as Hunt noted, “A united Germany, seen as impossible last year, seems inevitable today.”

A review of those occasions reveals that the honorands from Germany were frequently prescient, in ways that resonate—reassuringly or disquietingly—upon the occasion of Chancellor Merkel’s address.

“The people of the West…are impatient.”

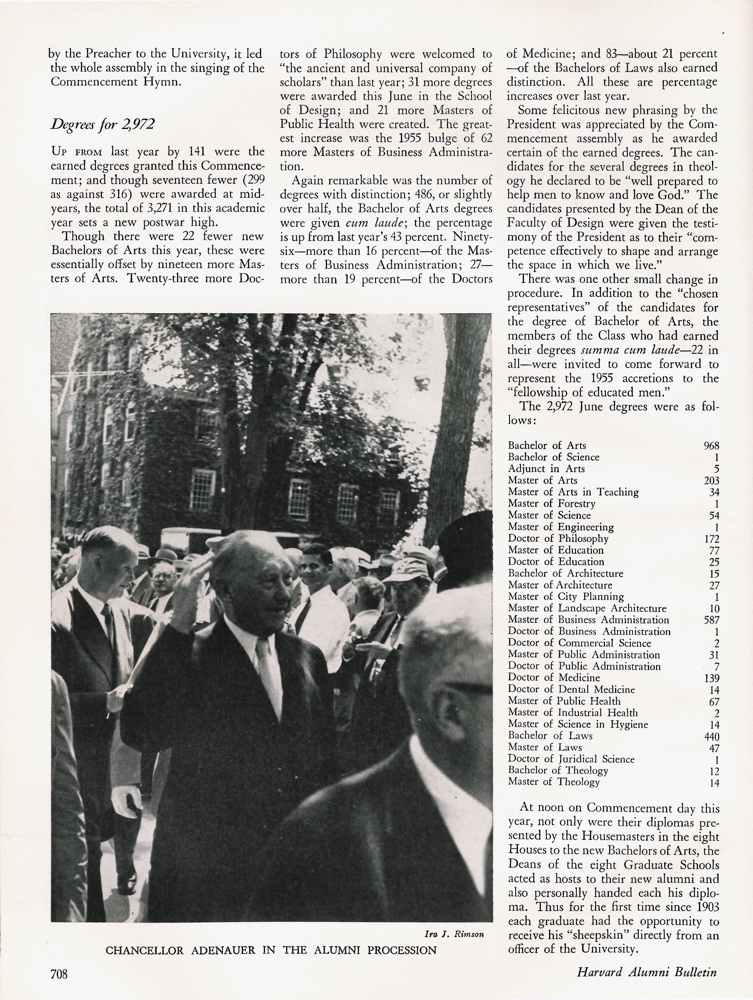

Click on image to enlarge: Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, in procession in 1955, during the height of the Cold War

Konrad Adenauer

From the July 2, 1955, Harvard Alumni Bulletin’s reporting on the 304th Commencement, which took place on June 16, under the calendar then in effect.

Chancellor Adenauer’s citation read: “Resolute statesman of German reconstruction, energetic champion of peace and unity in Europe, he has restored his country to a place among the nations.”

Come the afternoon talking parts (which also included a role for Luis Muñoz Marín, governor of Puerto Rico, in the news again in 2019, given its recent devastation by hurricane, its prior financial troubles, and its rocky relationship with President Donald Trump), Adenauer was introduced by no less a Harvard figure than James Bryant Conant, president emeritus, U.S. ambassador to the Federal Republic of Germany. The Bulletin ran the text of his remarks, in translation from the German.

Adenauer said that “An honorary doctorate from Harvard University…is a mark of great distinction. That this distinction was conferred upon me here today is an especial honor and pleasure for me.” After thanking Conant, “who has achieved so much by bringing the United States and Germany more closely together,” he acknowledged a darker period, and another deep tie to the University: “During the National Socialist times Harvard welcomed to its faculty many German scholars, generously granting them asylum and the opportunity to carry on their work. For this, too, I wish to express my heartfelt thanks to Harvard University.”

He reviewed international relations in the then-Cold War, in a way that resonates today. As he spoke, he said, “the West, the free peoples, are now stronger than they were previously” because of steps to unify Europe, including the entry of the Federal Republic into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization” (NATO), in pursuit of a common defense, “in which the United States has taken the lead.” The Soviet Union, he suggested, had to become less aggressive, given that “her population suffers great want.” In the period ahead, forces were aligned for progress because “the great international tensions which afflict the world are related to and connected with one another. I think it is universally accepted that no single great problem can be approached independently.” Done correctly, through “hard, long, and tedious work,” diplomacy could “accomplish something worthwhile and satisfactory,” lessening “worldwide tensions.”

In negotiating with the Soviet Union, in part to effect the reunification of Germany, Adenauer said:

For the people of the West time is important and therefore they are impatient and they press for an immediate and visible success. Time means nothing to the Russians; they are interested only in space and not in time. In this they have a definite advantage in negotiations which by their very nature are most complicated. In my opinion, the West cannot have enough patience, nor show enough firmness and perseverance. Under no circumstances may the West—and let me repeat here a little more strongly what I have said before—by impatience undermine the position of its representatives in their laborious negotiations.

“The prevention and the absence of war is neither the only thing nor everything we want to attain.”

Click on image to enlarge: Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, the 1979 honorand and speaker, famously captured taking a pinch of snuff

Helmut Schmidt

From the July-August 1979 Harvard Magazine, reporting on the 328th Commencement, which took place on June 7—in a year of campus protest about boycotting and divesting from companies involved in South Africa, during a period of détente between East and West.

Chancellor Schmidt’s citation read: “In gratitude for the legacy of German learning, this university hails the progress of a democratic Germany and warmly welcomes her illustrious leader.”

The magazine noted that security was heavy for the day, and reported that Chancellor Schmidt took the stage with his “omnipresent cigarette”—and even published a picture of him indulging in a pinch of snuff, with President Derek Bok observing his technique.

Delivering his address in English, it reported, “Schmidt spoke easily of Germany’s position within NATO and the European community at large; of his country’s continuing trust in United States support; and of the need to maintain an ‘equilibrium’ between East and West—and the continuity of the policy of détente on the basis of that equilibrium. ‘We are living in an economically interdependent world of more than 150 states, without having enough experience in managing this interdependence,’ he warned.” He vigorously embraced SALT II as a means to limit arms cooperatively, “a prerequisite for the military and political stabilization of the East-West relationship,” while warning that “détente, of course, cannot ever eliminate differences in values and ideals, and in political and social systems.”

Presciently, he discussed energy, the magazine’s account said (albeit in a context different from today’s concerns about climate change), “as an essential element in the preservation of peace and world security.” The chancellor said, “We cannot ignore any source of energy—solar, geothermal, or nuclear….”

His conclusion moved to a higher plane—again, a message that continues to resonate, only if aspirationally, in an era newly riven by nationalist rhetoric and heightened competition among many countries around the globe:

The prevention and the absence of war is neither the only thing nor everything we want to attain. We want to advance from a partnership for security between East and West towards a partnership for cooperation.…I feel confident that freedom, the basic rights of the individual, and the principle of the dignity of man are on the march and cannot be stopped.

“Europeans believe that their American partners are marked by erratic confusion.”

Richard von Weizsäcker

From the July-August 1987 Harvard Magazine, reporting on the 336th Commencement, which took place on June 11; it noted that the guest speaker’s selection, to address the crowd (during the fortieth-anniversary year of the famous Marshall Plan Commencement talk) was criticized because of his father’s Nazi past—and was defended by Rabbi Ben-Zion Gold of Harvard Hillel and by Henry Rosovsky, former Faculty of Arts and Sciences dean, a Corporation member, and himself a refugee from Nazism.

President Weizsäcker’s citation read: “In his homeland an honored figure of integrity and moderation, on the world stage the admired leader of a nation firmly committed to North Atlantic security and European democracy.”

Weizsäcker celebrated Secretary of State George C. Marshall’s visionary support for Europe, grounded in his strengths not as “an ideologist but a realist.” He went on to note that after four decades of successful alliance,

Yet there is some ill feeling between America and Europe. Many Americans regard us Europeans not only as strong economic rivals but above all as affluent egotists who constantly criticize America but are not able or willing to think in global dimensions, to bear our fair share of burdens, or to discharge our political responsibilities properly. They view us as wavering partners with a provincial outlook. Some may want to go so far as to call us “Euro-wimps.”

Looking in the other direction, Europeans believe that their American partners are marked by erratic confusion. On the one hand, American supposedly claim a rather unilateral leadership role in the world. On the other hand, an inward-looking mentality often seems to prevail. Many feel that the Americans are living beyond their means. They regard the huge twin deficit in the United States budget and trade balance as imposing a great burden not only on the Americans but also on others in the world. They point out that the Americans produce less than they consume and save less than most other countries but as the world’s richest nation draw on a disproportionately large share of the world’s savings to offset this deficit.

Withal, he found common ground, in that “our societies share fairly similar weaknesses,” because their democracies “do not educate us to pay attention to the problems of other countries, although our own destiny is strongly linked to their fate.” All too often, he continued, “[W]e are captives of local and regional interests and demands, tied down like Swift’s Gulliver by countless little ropes and chains. It seems as though everywhere provincialism has taken charge of us, as though all of us are dominated by a shrinking horizon and a parochial inward-looking mentality.”

He summoned the spirit of the Marshall Plan to address both the problems of the Third World, and the persisting challenges of East-West relations. “George Marshall set an example,” Weizsäcker said. “We should complete what he so ably began.”

“If Europe and America combine their intellectual and material resources….”

Click on image to enlarge: Chancellor Helmut Kohl, giving his address, 1990, and acquaintance Richard M. Hunt, University marshal

Helmut Kohl

From the July-August 1990 Harvard Magazine, reporting on the 339th Commencement, which took place on June 7. The magazine noted that Senior English Orator Noam Bramson talked about his Jewish father’s escape from Poland during World War II—one of only 500,000 of Poland’s 3.5 million Jews who survived to the summer of 1945.

Chancellor Kohl’s citation read: “Called to a mighty task in a time of miracles, he can help to heal the last wounds of war, to build a just peace, and to renew on this good earth hope for the age prophesied of old, when all shall dwell secure and none shall make them afraid.”

Click on image to enlarge: The chancellor and his family, in a private capacity: attending son Walter’s graduation in 1989

Kohl, speaking in German, first conveyed a family message on son Walter’s behalf: “Mather House is the best House.”

Turning to matters geopolitical, with a healthy dose of optimism, he forecast that “by the end of this century the foundation stone will have been laid for a United States of Europe,” including members of the European community but with a large role for the United States: “If Europe and America combine their intellectual and material resources…they will invest in their common future.” The investment, he said, “will benefit all of us.”

Next up, the long-serving Angela Merkel.