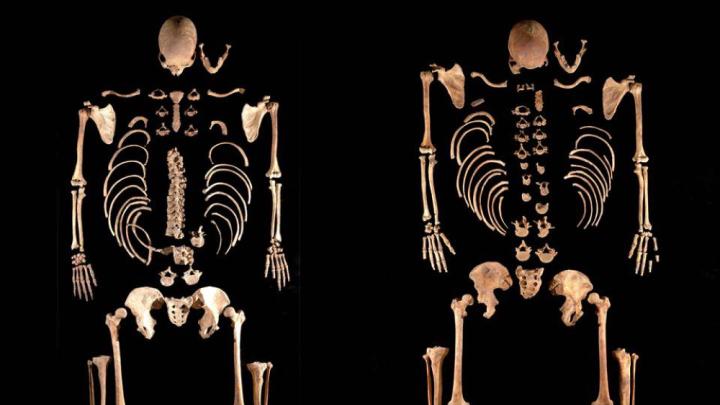

What secrets do the ear bones of long-dead skeletons hold? Not ancient stories or sounds, but DNA. Genetic material from these human remains provides the basis for a new history of Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal), published today in Science by an international team of researchers at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona.

The DNA, from hundreds of humans spanning more than 8,000 years from the Neolithic era to the 1500s C.E., tells many tales: it reveals a heretofore unseen, Stone Age migration through northern Spain some 8,000 years ago, Bronze Age immigrants from North Africa more than 4,000 years ago, and multiethnic Greek and Roman cities during those civilizations’ respective heydays. Most striking, perhaps, is a finding from the Bronze Age: one migration from central Europe replaced nearly the entire male population of Iberia between 4,500 and 4,000 years ago, raising a host of questions about sex and culture in that region at that time.

The research is the latest study of ancient DNA from the lab of David Reich, a professor of genetics in HMS’s Blavatnik Institute, who has positioned himself as a juggernaut in the growing field of paleogenomics, the study of these ancient genomes. By comparing genomes from ancient sites with each other and with modern genomes, Reich and his collaborators have traced human movement around the globe from the origin of our species (see “Human-Family Reunions,” July-August 2014) to the prehistoric migrations of ancient peoples (see “Genetics and the Human Revolution,” October 2018), questioning old archaeological narratives and postulating new ones.

One new story is the case of the vanishing Iberian men. About 4,500 years ago, a new population group showed up in Iberia. Unlike the preexisting occupants, whose ancestors seem to be a mix of Iberian hunter-gatherers and farmers who had arrived thousands of years earlier from present-day Turkey, the new group had genes most similar to peoples who had earlier migrated into central Europe from the steppes north and east of the Black Sea. (Previous research has indicated that this group’s movement may have brought Indo-European languages to much of Europe.) This steppe ancestry group and the preexisting Iberian populations seem to have co-existed throughout the region for centuries, with minimal interbreeding. But when the populations did start mixing, they did so in a “sex-biased” way, as revealed by the Y chromosomes, present only in men: the steppe group’s Y chromosome type became increasingly common, while the preexisting occupants’ Y chromosome types essentially vanished over the course of barely 200 years. For some reason the steppe males were fathering far more children than males from the preexisting groups. (For more on a similar event, see “Who Killed the Men of England.”)

A previously unreported migration that replaced the entire male population of a region the size of Texas is the sort of grand addition to the past that has drawn both acclaim and fierce criticism to Reich and paleogenomics. A January story in The New York Times Magazine cited complaints from archaeologists and geneticists that Reich and a handful of other ancient-DNA labs monopolize archaeological data sets and publish ambitious stories with more certainty than their genetic samples warrant. This, say the researchers, leaves them with a dilemma: surrender their data to Reich for mention in a flashy paper in a top-tier journal, or go it alone without access to his vast resources and collaborations and risk being scooped. (Reich responded to such sentiments in an open letter to the Times, questioning the critiques’ grounding in “incomplete facts and largely anonymous sources whose motivations are impossible to assess.”)

But the Harvard researchers are quick to point out that the stories from the Iberia study are more complex than they may look at first. Whatever happened to the Iberian men, for instance, began only after the two groups had lived together throughout the region for centuries. “Iberia at this time,” Reich said in a phone interview, “is a multi-ethnic society” until somehow “that population substructure where these groups aren’t mixing breaks down everywhere we sampled.”

Something changed dramatically about 4,200 years ago. What that was is unknown, but the researchers caution against assuming the worst of the interloping males. “It would be a mistake to jump to the conclusion that Iberian men were killed or forcibly displaced,” said Iñigo Olalde, a postdoctoral fellow in Reich’s HMS lab and first author of the paper, “as the archaeological record gives no clear evidence of a burst of violence in this period.”

Genetics, in other words, can tell us when the Iberian males vanished, but not why that didn’t happen 300 years earlier, or whether it was due to war, slavery and subjugation, the cultural preferences of Iberian females, or some combination.

“A finding like this motivates us to go back to the archaeological record,” Reich said in an email. “To try to understand if there might be archaeological processes that we hadn’t appreciated before that might be related to this phenomenon.”

The further revelation that the Basques in northeastern Iberia share significant ancestry with the steppe people of the same Bronze Age migration raises similar questions. Genetics can indicate that the steppe people mixed with the Basque people’s ancestors. But it cannot tell why the steppe people’s Indo-European language, which spread alongside their genes nearly everywhere in Europe, did not spread to the Basque regions. “Other fields such as archaeology and anthropology need to be brought to bear to gain insight into what shaped these genetic patterns,” said Reich.

Though the study throws the limits of genetic inquiry into stark relief, Reich said over the phone that the data from hundreds of ancient remains and thousands of present-day humans enable his team “to do something that was not possible a few years ago”: to identify outliers “whose ancestry doesn’t match the majority group at the site.” One such example, a 4,000-year-old man found near Madrid, had mainly North African ancestry. “Probably a first-generation immigrant,” said Reich. “Despite that, this individual is buried in a culturally typical way in that site.”

What brought that man to central Iberia, thousands of years before the Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans made travel across the Mediterranean more commonplace? Did he follow the same long-forgotten trade routes that brought ivory to other sites around Iberia? When he died far from home, why did the local people bury him like one of their own? This kind of discovery, in Reich’s words, “is documenting that history is complex.” The rich genetic data serve as a reminder that, though they are often framed as sweeping migrations and population replacements, the life stories of individual ancients were no simpler than our own.