Conjure your image of a Native American. Modern Americans might first think of American Indians as relics of the past, their memory consigned to kindergarten Thanksgiving dress-up and Hollywood Westerns. But much as they are marginalized in the story of America, American Indians are also central to the American cultural imagination—both erased from and incorporated into the national narrative. Philip J. Deloria, professor of history, began to explore this seeming contradiction in his first book, Playing Indian (1998), writing about white people dressing up as Native Americans, or “playing Indian,” from the Boston Tea Party through the present.

Quoting the French-American writer J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, Deloria asked, “What, then, is the American, this new man?” American national identity, he argued, rests on the image of the American Indian. In the eighteenth century, colonists rebelling against the British crown often wore Indian disguise to assert an authentic, indigenous claim to the American continent. At the height of industrialization and urbanization, Americans played Indian to counter the anxieties of the modern world. And even as Indian play might sound esoteric, it strikes a deep chord: readers who grew up in the United States have likely, at some point, played Indian.

Adapted from Deloria’s dissertation in American studies, which he finished at Yale in 1994, Playing Indian is a vivid, mind-expanding, and lucid telling of American history, even as it is deeply theoretical. The book changed the field of Native American studies and U.S. history, offering a new way to understand Native Americans’ place in the nation’s culture and past. “It had a massive impact,” says Jay Cook, a historian and former colleague at the University of Michigan, in part because it was a fundamental shift in Native American history. “The field had previously tilted more toward the social sciences…and things like land usage, or treaties, or the politics of removal and genocide and colonial contact.”

Boy Scouts alongside an Indian "adviser" get ready to perform a dance in Indian costume, Denver, 1977.

Photograph by Denver Post via Getty Images

Deloria made Native American history about culture. He was interested in big, fluid questions about representation and how different social groups are perceived. He did not treat Indian play merely as a curiosity, or condemn it as misappropriation of Native American identity (as he might reasonably have done). Instead, he took disguise seriously, as a means of working through social identities that were complex, contradictory, or hidden to the people who participate in them. “Disguise readily calls the notion of fixed identity into question,” he wrote. “At the same time, however, wearing a mask also makes one self-conscious of a real ‘me’ underneath.”

Deloria, who turns 60 this year, became Harvard’s first full professor of Native American history last January, after 17 years at Michigan and six before that at the University of Colorado. In person, with his easy lilt and vital, chatty demeanor, it’s easy to imagine him on stage, playing country-western music with his friends—still a favorite pastime after his failed first career as a musician.

Talking about his work, he is both buoyant and deadly serious. He remembers conceiving the idea for his dissertation while sitting in a lecture. “It literally unfolded in about a minute,” he says. “It was one of the most amazing thought moments of my life.” Projected on the screen were historic images of Boy Scouts dressed up as Indians. Fellow graduate student Gunther Peck, now a history professor at Duke, turned to him and said, “This reminds me—have you heard of the Improved Order of Red Men?”—the nineteenth-century fraternal society that provided its members communion and common purpose through “Indian” dress-up and rituals. Deloria’s mind suddenly threaded the needle from the kids on the screen to Indian-themed fraternal societies to Boulder, where he lived for years and “where all the hippie New-Agers dress up like Indians and make a big deal out of it. And then it’s not hard to go to the Boston Tea Party. I was like, damn, Americans have been doing this in different forms, but with similar practice, from the very beginning. I wonder what that’s about.”

At bottom, Playing Indian is an assiduous work of cultural history. Deloria traces Indian play to the old-world, European traditions of carnival and “misrule,” or riotous parties and rituals that involved costume, symbolic effigy burnings, and riots. “Both sets of rituals,” he wrote, “are about inverting social distinctions, turning the world upside down, questioning authority.” He showed how costume would have felt natural to early American settlers, allowing them to subvert power structures and play with their individual and cultural identities. Indian disguise was adopted throughout the colonies not just to protest the British, but also to defy unpopular land-use laws and play out social conflicts.

Later, during the mid nineteenth century, a young Lewis Henry Morgan, a pioneering anthropologist, played Indian as part of his literary society, the New Confederacy of the Iroquois. Like other fraternal societies, the group aimed to revive the spirit of the “vanishing” American Indians and build from it a distinctly American identity. Their rituals would lay a troublesome foundation for Morgan’s ethnographic work: they presented a nostalgic and stylized picture of Indians even as his career advanced and his aim became to objectively and scientifically document American Indian societies. This idea of anthropological accuracy, of authenticity, would transmute during the twentieth century, when modern Americans played Indian to reclaim a relationship with the natural world. “In each of these historical moments,” Deloria found, “Americans have returned to the Indian, reinterpreting the intuitive dilemmas surrounding Indianness to meet the circumstances of their times.”

“Have Fun with the FBI Agents”

In many ways, Deloria might have seemed predestined for a preeminent career in Indian studies. His great-grandfather Tipi Sapa, also known as Philip Deloria, was a prominent Yankton Sioux political leader who converted to Christianity and became an Episcopal minister, and his grandfather, Vine Deloria Sr., also entered the clergy. His father was Vine Deloria Jr., a professor and activist who served as an executive director of the National Congress of American Indians. Most famous for his 1969 book Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto, a blistering, yet often humorous, appraisal of the country’s relationship with American Indians as well as a call for Native self-determination, Vine was one of the most influential figures in twentieth-century Indian affairs.

Growing up, Philip was aware of his father’s stature, and of the importance of what was happening around him. He remembers American Indian activists and artists passing through his house, and being enlisted to stuff envelopes for his father’s political efforts. “There was a moment during the Wounded Knee trials when the phones were tapped, and he told us…‘Have fun with the FBI agents.’” His mother was worried after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, Deloria says: “You had the sense that bad stuff was happening to people.”

But Deloria didn’t directly inherit his father’s role as political advocate. “When he became director of the National Congress of American Indians,” he says, “we didn’t see him for, like, nine months.…There were moments when he’d rise to being a great father. But for the most part, he was not. He was doing his thing. It was super important—we all got how important it was.” As a result, Philip and his brother and sister “could do whatever.” He was drawn to music and sports; he started as a performance major at the University of Colorado, then switched to music education after realizing he was not going to make a living as a performer. He taught middle-school band and orchestra, but quit after two years. He got married around the same time: “My father-in-law was not that happy with me.” It was the ’80s, during the rise of MTV, and he became obsessed with making music videos. “If you look back at the last three of four generations of Deloria men, they screw around until they’re 30,” Vine Deloria told him. “They look like complete losers.” Philip went back to the University of Colorado for a master’s in journalism, to get access to video equipment, and to try to make a hard turn in his life.

“I couldn’t figure out music, or journalism, or what,” he says. After that, he applied to Yale’s doctoral program in American studies, at the encouragement of Patricia Limerick, a historian of the American West whose class he took for his master’s. He didn’t have the academic preparation of most of his peers and hardly said a word in his first year of classes. One of his fellow students said he wanted to be the next Michel Foucault. “Another guy said, ‘I’ve been reading the exam list on the beach this summer,’” he remembers. “I showed up at Yale and really, really didn’t know what I was doing.” But from the beginning, Deloria looked for deep, difficult explanations for culture. He combined his American studies work with courses on European social theory. “His early papers were hyper-theoretical, with a lot of jargon—he started out that way, harder to read,” remembers historian and public artist Jenny Price, a friend from graduate school. “By the second year, it was clear he was going to be a fine writer and really a standout.”

Undercutting the “Easy Takeaways about U.S. History”

The flip side of Indian play, Deloria discovered, was that nostalgic or romantic images of American Indians put Native people in an impossible position. It made it difficult for them to participate in modern society, while also treating them as victims of modernity, whose traditional societies have been steamrolled by civilization. Even ostensibly reverential forms of Indian play, like mid-century powwows or the rituals of hippie counterculture, have always hinged on the idea of the “vanishing Indian,” an ideology of inevitable replacement of Native Americans by U.S. dominion.

Members of the Wildshoe family, of the Coeur d’Alene people, pose in their Chalmers automobile, 1916.

Photograph from the Library of Congress

Deloria treated these issues in his second book, Indians in Unexpected Places (2004). The book is almost a mirror image of Playing Indian, covering Native Americans participating in modern life—in film, sports, cars, music, and elsewhere—during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a period when many were relocated to reservations and allotted arbitrary parcels of carved-up land. What is so funny and surprising to many Americans, Deloria asked, about a photograph of Geronimo behind the wheel of a Cadillac? Readers might imagine that at the dawn of modernity, Native Americans just dropped out of history. But “American Indians were at the forefront of a lot of things we consider quintessentially modern, like making movies and car culture,” says Carlo Rotella, another Deloria friend from graduate school, who is now director of American studies at Boston College, where he teaches Indians in Unexpected Places in his courses.

“It just seemed wrong, somehow, that Indians should leap from ‘primitive hunter-gatherer’ status…into the cutting edge of technological modernity, without moving through all the other stages!”

Significant numbers of Native people were buying cars at the turn of the twentieth century for business or to cross the long distances across reservations, and cars, in turn, shaped the evolution of modern American Indian practices, such as the powwow. “White Americans were outraged,” Deloria said at a 2005 talk, “for Indian drivers went square against the grain of their expectations. Viewing Native people through the lens of social evolution, it just seemed wrong, somehow, that Indians should leap from ‘primitive hunter-gatherer’ status…into the cutting edge of technological modernity, without moving through all the other stages!” Deloria’s aim in the book was not to highlight Indians in modernity as anomalies—it was to dispute that very idea, and assert American Indians as real participants in the creation of modern life. He contrasted the marginalization—the unexpectedness—of Native people in modernity with that of the African-American modernist movement: “The Harlem Renaissance can be named as a discrete thing,” he said, “which is more than can be said for the cohort of Indian writers, actors, dancers, and artists also active in the modernist moment.”

Deloria is ever observant of the problems that representations of American Indians have created for living Native people. “Phil is deeply humane and deeply ethical in the way that he frames questions,” says Gunther Peck, still a close friend. “He pursues answers that are disquieting and that cut against some of the easy takeaways about U.S. history.” He considers issues, Rotella adds, “for which we haven’t had much of a vocabulary before, other than ‘That’s racist’ or ‘That’s cultural appropriation.’” Deloria’s deep historical and interpretive work provides answers that are not only more interesting, but also more helpful and revealing. He draws a complete, tangled picture of how U.S. culture came to be, and how it might harm Native people even when it appears to repudiate the violence of the past.

“Go to Harvard”

Deloria’s research has distinguished him as perhaps the world’s leading thinker on American Indian studies. He also co-authored, in 2017, a new introductory textbook to American studies, the interdisciplinary field that draws on history, politics, culture, literature, and the arts to understand American society. Shelly Lowe, executive director of the Harvard University Native American Program (HUNAP), which since its founding in 1970 has advocated the recruitment of Native faculty and scholars of indigenous issues, hopes that Deloria’s appointment will put Harvard on the map for Native American studies.

The University had been recruiting Deloria for years, Lowe says, not just as the top scholar in his field, but also as an outstanding classroom teacher and a capable administrator who can shape a coherent Native studies program. “There’s a severe lack of understanding of what Native American studies is as a discipline, because it’s never been something that Harvard has really offered,” she explains. “Phil is going to be the leader in that realm.” (Since his appointment, the University has also hired professor of history Tiya Miles ’92, who focuses on African-American and Native American studies, and her husband, Joe Gone, professor of anthropology and of global health and social medicine, who studies public health in American Indian communities.)

Rotella adds that Deloria “exudes competence,” and keeps being appointed to run things as a result. Recently, he was named chair of the committee on degrees in history and literature. This past fall, he taught “Major Works in American Studies” and “American Indian History in Four Acts,” and in the spring, he will teach “Native American and Indigenous Studies: An Introduction.” Part of what made it difficult for him to move, Deloria says, was his wife’s career. Peggy Burns joined Harvard last April as executive director for corporate and foundation development and relations; previously, she was chief development officer for the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, and before that, a top fundraiser at the University of Michigan. Says Deloria, “She’s the lead partner, I’m the trailing spouse.” As for why he chose Harvard: “Harvard has so many opportunities…If you thought, in the last few years of your career, that you could make a real impact in the field, you might think to yourself, ‘Go to Harvard, use the resources here, train some great grad students, help out the interesting Native undergrads who are here, write a couple good books, see what kind of impact you can make.’”

Indigenizing American Art

Deloria’s new book, to be published this spring by the University of Washington Press, builds on the foundation of its predecessors. If Indians in Unexpected Places represented a call to recognize Native Americans in modern culture, then Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract is, in part, an answer to it. Part biography, part history of American modernist art and its tangled relationship with Native people, the project began in 2006, when Deloria and his mother thumbed through the drawings of his great-aunt Mary Sully. The pictures, carefully preserved by his mother, a librarian, were virtually unknown to the outside world, but as Deloria would discover after talking with other scholars and conducting his own investigations into art history, they were remarkable. “I think she belongs in the canon of American art, and I think she’s transformational of that canon,” he said at a talk on Sully last February. His project in the book, he explained, is to “indigenize American art.”

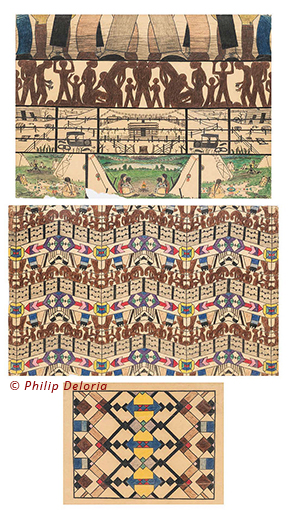

Mary Sully’s Three Stages of Indian History: Pre-Columbian Freedom, Reservation Fetters, the Bewildering Present imagines a vision of the future.

Artwork courtesy of Philip Deloria/Photograph by Scott Soderberg

Mary Sully, born Susan Deloria, was the sister of Ella Deloria, a well-known ethnographer and linguist who worked for anthropologist Franz Boas (“I’m going to inflict yet another Deloria onto the world,” Philip jokes). They grew up on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in South Dakota, the granddaughters of Alfred Sully, a nineteenth-century military officer who led campaigns against American Indians in the West, and great-granddaughters of Thomas Sully, an eminent portrait painter. (Alfred Sully’s daughter with Pehánlútawiŋ, a Dakota Sioux woman, married Tipi Sapa/Philip Deloria, unifying the Sully and Deloria lineages.) Deloria surmises that Susan embraced Thomas Sully’s name to evoke his stature in American art; identity doubling was also an important concept in Dakota women’s arts. Sully was most active in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s; she had little formal artistic training, and no artistic community with which to share and reflect on her work.

Sully’s pencil-on-paper drawings comprise mostly what she called “personality prints,” 134 in all (plus a few unfinished ones), each depicting a personality (famous or not) from the 1930s. Some prints depict Native American subjects, such as The Indian Church or Bishop Hare, a leading missionary among Dakota Indians; others represent figures from pop culture, like Babe Ruth, Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, and tennis star Helen Wills. Each work consists of three panels: the top one, Deloria writes, is usually an abstract depiction of the person or concept; the middle panel is a geometric, patterned design; and the bottom one is what he calls an “American Indian abstract”—a variation on the themes of the work that draws from American Indian visual possibilities.

Mary Sully’s drawings invite viewers to imagine Indianness in American mass culture, and in the fabric of America itself.

One particularly haunting print, Three Stages of Indian History: Pre-Columbian Freedom, Reservation Fetters, the Bewildering Present, holds a “master key,” Deloria says, to understanding the political content of Sully’s work. She created it while the Native community was grappling with the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, a complex, highly contested restructuring of federal Indian policy with consequences that reverberate today. The top panel narrates Native American history: an idealized past before European contact, the trauma of reservations, contained by barbed wire, and the struggle of Native people against distinctly American figures in jeans, boots, and a pinstriped suit. In the middle panel, a visually complex pattern abstracts away from the scenes of the top into a dense, geometric composition, producing a sense of disorientation, anxiety, and uncertainty. The bottom panel, in Deloria’s reading, turns the middle panel 90 degrees, transforming it into a symmetrical Indian pattern. The barbed wire and struggling figures from the previous panels have disappeared; their browns and blacks now form strips of vertical diamonds. “At the center,” he writes, “and overwriting the barbed wire, is a single band of color. Yellow, blue, red, and green,” colors from Plains Indian parfleche painting, form a strip of diamonds. This panel evokes Indian strength and continuity, contrasting with the panel above it.

How to read this image? Sully’s title, Three Stages of Indian History, provides a clue. The top panel represents the present; the middle, a transition; and the bottom, the future. The bottom panel provides a vision of Indian futurity, Deloria argues, insisting on the participation and centrality of American Indians in the future rather than confinement in the past. This interpretation also provides a general approach to reading Sully’s personality prints. Taken together, the prints evoke a full range of human experience—playfulness, joy, wonder—in a Native visual vocabulary. They invite viewers to imagine Indianness in American mass culture, and in the fabric of the United States itself. In this way, Sully was among the group of indigenous visual artists active in modernism, the movement that embraced abstraction, experimentation, and the use of geometric forms. Deloria writes: “The diamond is as central to Native women’s arts as the grid is to the modernist—and yet Sully made them one and the same, dialogic and simultaneous.”

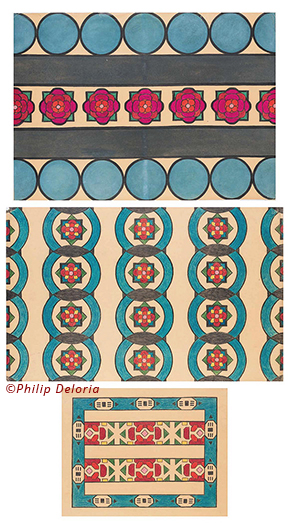

Gertrude Stein is among Sully's many prints depicting artists, actors, athletes, and other celebrities from American pop culture.

Artwork courtesy of Philip Deloria/Photograph by Scott Soderberg

But Sully’s work also provides a challenge, and thus a distinct contribution, to the canon of American art. She was not part of the group of modernist artists, including some Native artists, known as “primitivists,” who looked backward toward “primitive” aesthetics and experience. She was not captivated by visions of a romantic, pre-modern past. Sully was interested in American Indians’ relationship to the present and future; she was, as Deloria terms it, an antiprimitivist. Other Native artists, who received financial support from arts institutions, created images of Indians in the past that appealed to white viewers. Because Sully never received any patronage, and her art was never publicly viewed save for a few exhibitions at children’s schools, she was unconstrained; she could create images of Amelia Earhart or Gertrude Stein in an American Indian abstract. No one saw her work, yet she changes the story of American art.

Becoming Mary Sully, like Deloria’s earlier books, manages to feel both concrete and abstract. It tells an engrossing story while also pivoting at each turn to artistic, historical, and moral implications. It is also a striking intervention into the history of visual art. Carlo Rotella calls this Deloria’s “human Swiss Army Knife” quality. “The typical thing with Phil is, he’ll say, ‘I don’t know much about x, so I’m going to have to find out about x.’ And the next thing you know, he’s made a masterly argument about x in which he’s saying something totally new that no one has said and ends up doing the definitive work on that subject.”

“The Last Thing We Think About”

Deloria, unlike his father, has never acquired a reputation for polemics or for being particularly tendentious in his writing; he is a different type of scholar. “You knew when you were in a room with Vine Deloria,” says HUNAP’s Shelly Lowe. “You may not know when you’re in a room with Phil Deloria.” The son’s differences with his father are of a piece with how lightly he wears his association with the Deloria family. Jenny Price remembers when, in graduate school, he began presenting the material that would become Playing Indian at conferences. “Almost inevitably, some outraged person would stand up and say, ‘How can you presume to talk about Indians as a non-Indian?’” she recalls. “My sense was always that the reason it would happen is that he wasn’t performing Indianness in the way people thought he should. Phil would never start his answer with, ‘I’m an Indian, my name’s Deloria, for God’s sake.’ Because how do you even define that? He would start to say, ‘Well, my great-great-great-grandfather was this person, and then he married this person.’”

Still, Deloria’s work is personal and political, even as it is analytically careful. He doesn’t believe there could be a coherent way to cleanly separate scholars’ personal identity from their interests and research agendas: “There is something about my interiority that gets me to think and ask questions in a certain way.” When talking about diversity categories, he says, there’s a sequence in which people list them: African-American, Latinx, Asian-American, Native American. Many people reciting that list might not think they’re setting up a hierarchy, “but I see a hierarchy. I see the fact that Native people make up 1.7 percent of the population and that means they always get stuck last. They’re always the last thing we think about,” he continues. “And I get unhappy. And that unhappiness is part of my interiority.”

But “this is not a moment when any of us are thinking very well about these things,” he continues. In his view, much of what should be the subject of private thinking has become a public performance, and “It’s not been that productive.…We’ve had a lot of identity policing, and ways in which people are trying to figure out how to perform a better identity. If we can think about how we [can] do these things in a good way, in a right way, in an honorable way, in a humble way, that would be useful and productive.”

Recently, Deloria has been thinking more about the relationship between Native American and African-American studies, and those hierarchies that exist among different identity groups. He considers how his children learned the usual story about black history in school: “It’s all about the progressive narrative that leads us to civil rights. ‘America really was fundamentally good, but it took us a while to get there.’…

“But how do you do that with a Native American narrative? You don’t have the same kinds of redemptive possibilities. So all you can do is erase Indian people, and retell the story in which we all got along pretty early because the Indians pretty much handed off the continent to white people.” There is no better narrative, he says, “because the narrative would be, ‘Look at the ground our school’s on; look at your playground. Who owned that land? How did it come to be our land? Was it a clean process? Is it over? Do you think there are Indian people out there? Oh, there are?’ All of a sudden the complications just get too hard.

“So part of this is thinking, can a country deal with more than one original sin at a time? And if it can’t, has the U.S. decided to deal with the original sin of slavery in a way it doesn’t deal with the original sin of settler colonialism? How do the two interact?” A question, perhaps, for another book—Deloria’s interdisciplinary, elastic way of thinking makes him an ideal person to answer it. The most revealing answers often lie in contradictions, his work has shown, and in the slippage between different narratives. He challenges readers to lose the assumptions that have caused Native people to be forgotten and persistently, but expectantly, asks more of America.