The best use of massive open online courses (MOOCs) may be in providing instruction that leads to online professional degrees—not the extension of basic college education to U.S. and international learners who do not have access to existing higher-education institutions. That conclusion is spelled out in a forum titled “The MOOC Pivot” published in the January 11 issue of Science. Co-authors Justin Reich and José Ruipérez-Valiente argue that low student retention and enrollment declines in MOOCs mean that their applications and effects differ significantly from the enthusiasm that accompanied the launch of the edX platform in the spring of 2012. The researchers use data provided by HarvardX and MITx—edX’s founding partners—from their courses offered from 2012 to May 2018; they argue that MOOCs “will not transform higher education and probably will not disappear entirely either.” Instead, they predict that the field will coalesce “around a different, much older business model: helping universities outsource their online masters degrees for professionals.” Their prediction seems to strike a blow at the heart of edX’s mission: to ensure access to quality education for learners around the world.

But critics of the study fault it for extrapolating from the data on MOOCs—typically offered free online as individual courses in a broad range of subjects already being taught to residential students—to paint a generally bleak picture of the potential for online learning in general.

The authors support their thesis—that MOOCs have failed to reorder higher education—by pointing to three patterns in the Harvard and MIT experiences:

- “[T]he vast majority of MOOC learners never return after the first year”;

- “[T]the growth in MOOC participation has been concentrated almost entirely in the world’s most affluent countries”; and

- “low completion rates” have not improved during the six years studied.

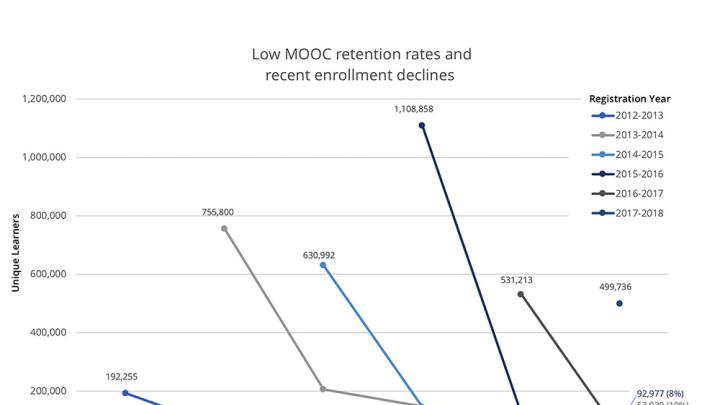

More than 80 percent of learners enrolled in the Harvard and MIT edX courses have come from countries rated high or very high by the United Nations Human Development Index. Furthermore, write Reich, an education researcher at MIT who previously worked at HarvardX, and Ruipérez-Valiente, a postdoctoral associate at MIT, the number of new individual learners, which increased from 2012 to 2016, has since declined. “In light of those trends,” write the co-authors, “financial sustainability for MOOC platforms may depend on reaching smaller numbers of people with greater financial means that are already embedded in higher-education systems rather than bringing in new nonconsumers from the margins.”

Although studies comparing learner achievement in online courses to residential campus instruction teaching the same content have documented comparable results among students at elite universities, Reich and Ruipérez-Valiente point out that if MOOCs are to reach first-generation college students, that “vulnerable” population may need substantially more human supports that “will push against lower tuition costs.” One of the notable advantages of online courses has been that they typically cost one-half to one-quarter as much as courses in campus settings.

The edX Perspective

Anant Agarwal, the MIT professor of electrical engineering who is founder and CEO of edX, says that research like that presented in the paper is one of the key tenets of edX’s operation as a nonprofit. But it misses the continuing growth in the edX platform overall, which includes 140 partner institutions offering 2,400 courses that have served 20 million learners. (Another 20 million learners have taken courses through institutions, including the governments of Israel, France, Russia, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and others, who are using the freely available open-source edX platform to launch their own educational initiatives). And it addresses only one of the revenue generating strategies—online professional degrees—that edX, now the largest learning platform in the world, is pursuing. Another is programs offered directly to businesses (200 business enterprises are now customers). And its third strategy involves educational offerings to individual learners, which had been free until recently. Edx announced in December, joining Udacity and Coursera, that free access would be limited in the future, with students seeking credentials or other services charged a fee to take courses on the platform. In that sense, the paper’s contention that a model of free MOOCs for all could not be sustained is at least partly correct.

“Universities have traditionally been focused on learners between the ages of 18 and 22,” Agarwal points out, and edX offers lots of content for that cohort—a natural extension of their residential curricula. (EdX also hosts a campus-focused platform for all its partners, which at MIT, for example, is used by 99 percent of undergraduates in their residential education.) But lifelong learners are a new audience for universities. “These consumers tend to be interested in paying for topics that are career-focused, that is indeed the case,” Agarwal says—“but only slightly more so than other sorts of courses. Writing and English-language courses are also very popular, as are many of the other humanities offerings.”

What is different is that these older individual learners, Agarwal continues, have been demanding programs rather than individual courses. “They are looking for sequences of courses,” he says, whether to “advance their careers or to make meaningful changes in their lives.” EdX thus began offering certificate programs and micro-masters programs three years ago. Ninety percent of those learners, in a recent survey, reported that they had experienced a career advancement as the result of a certificate program, whether in the form of a promotion, a pay raise, or a new job, he adds. Harvard’s certificate program in data science is one example of a course for which “learners are very willing to pay.” The first edX professional degree, the subject of the paper, was offered two years ago by Georgia Tech in data analytics. There are now 10 edX degree programs, including one, a masters in supply chain management, that starts with a micromasters through MITx, and ends with a degree from Arizona State University, at what Agarwal describes as “radically disruptive price points.”

Harvard Online

Byers professor of business administration Bharat Anand, who recently assumed oversight of HarvardX in his role as the University’s vice provost for advances in learning (he previously was faculty chair of Harvard Business School’s highly successful fee-based online programs, which are expected to generate surplus revenue in the next few years) also took issue with the MOOC paper’s conclusions.

“The paper does a nice job in summarizing some of what we have already learnt from the past few years of ‘the MOOC experiment’: merely supplying more content online, or better-quality content, or free content will not create transformational outcomes.” But the paper’s analysis of historical MOOC data “does a better job of interpreting what these data have meant for the early stages, and evolution, of MOOC platforms in particular,” Anand says, “than it does in extrapolating from them to draw implications about the future of online learning in general.”

Echoing Agarwal, Anand believes that “the next phase of on-line education will require a pivot in orientation— from simply focusing on creating more content online” to designing more programs “to accommodate the very different motivation, ability, and commitment of differently situated learners.”

Anand believes that Reich and Ruipérez-Valiente’s suggestion that the future of online education is restricted to professional-degree offerings is overly narrow. “Some of the big questions of our time are not only concerned with skills education or technology and data science, but [with] more deeply understanding politics, economics, and social structures, as well as fundamental issues like language and conversation, history, and human behavior. We are very excited at Harvard about the offerings we can provide across the entire range of disciplines that we teach—from the humanities to the social sciences to the sciences to professional education. Our experience suggests that there is strong interest in these subjects if material is well designed. And the forms these offerings take will be varied—focusing not only on traditional long-form courses but newer short-form offerings, not only web-based platforms but other delivery mechanisms, and not only asynchronous offerings but scalable synchronous online experiences too.” Unlike the professional-degree programs or Harvard Business School Online courses, however, these general offerings seem to lack a sustainable financial model, beyond reliance on philanthropic support.

Anand also notes that MOOCs represent only one part of the University’s online presence, pointing to institutional leadership in existing online-training programs that have demonstrated success at several different professional schools and in the Extension School. Although it is often career-enhancing programs that are most successful now, as the MOOC paper notes, Anand considers “the belief that the future of online learning in general will be limited to professional skill building, or online degrees only…misplaced…. With new tools, a breadth of disciplinary representation, and a learner-centric approach to content creation, I am excited about Harvard continuing to broaden and deepen its impact on learners throughout the world.” With deputy vice provost for advances in learning Dustin Tingley, a professor of government, Anand is concluding a multi-month strategic planning process around online education that he hopes will help shape “how individuals, universities, philanthropists and governments should think about online education.”

Agarwal agrees that it is much too soon to write off online education on the basis of an evaluation of MOOCs alone. “Edx remains committed to developing a sustainable business model, and making sure that we are able to reimagine education both in quality and scale for everybody, but it is going to take time,” he says. “Seven years in the grand scheme of things is a very short period of time to assess whether the technology has had a big impact” (although 40 million learners reached in every country in the world is a good start). “Once we get sustainable, and the non-profit begins generating a surplus, we can invest in quality and in reaching people we would not otherwise have reached.” Right now, he says, “I think we are just barely scratching the surface.”