On January 10, state transportation secretary Stephanie Pollack, J.D. ’85, announced that the state will rebuild the Massachusetts Turnpike at ground level where it passes through Allston, rather than maintain it on the existing elevated viaduct, which is currently in need of repair. The decision was the outcome of months of deliberation, the Boston Globe reported in a front-page story on January 11.

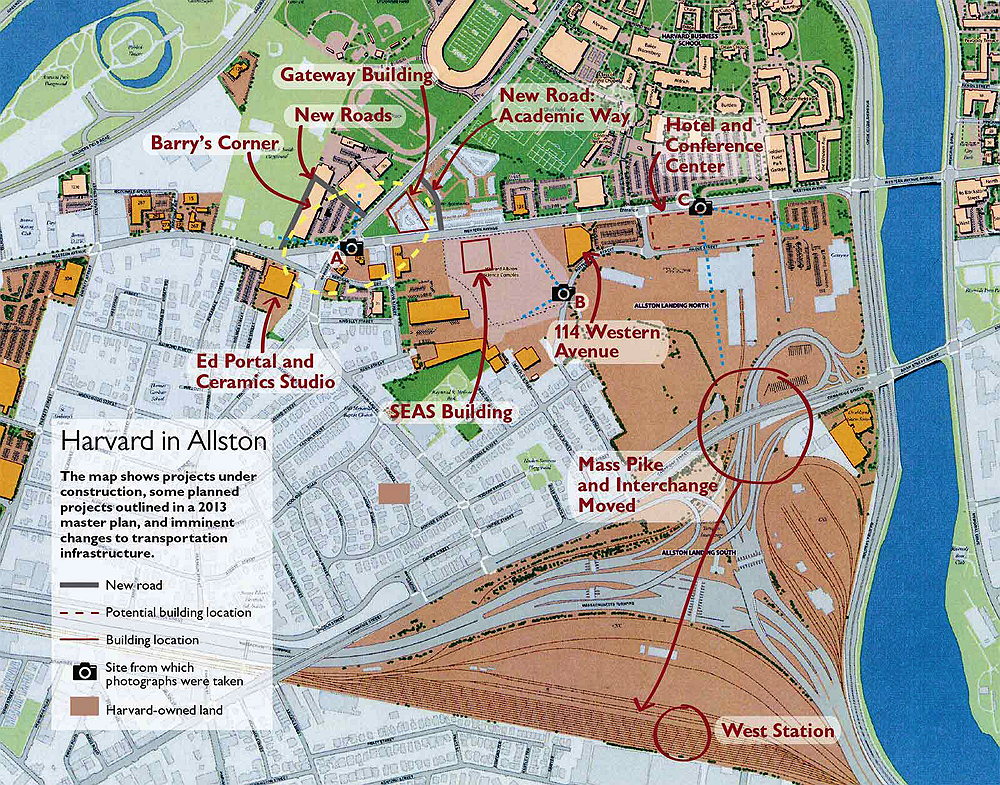

Rebuilding the turnpike in Allston to straighten the roadway and ease congestion at the Allston interchange has long been a shared goal of state transportation officials, local residents, and Harvard. The interchange is the scene of daily weekday traffic jams, and traces loops across industrial land and railyards that Harvard purchased in 2000 and 2003—totaling 90 acres, 50 acres of it potentially developable land—as part of its larger plans to expand its campus on the Boston side of the Charles River. The area remained encumbered by easements belonging to the rail freight company CSX until very recently.

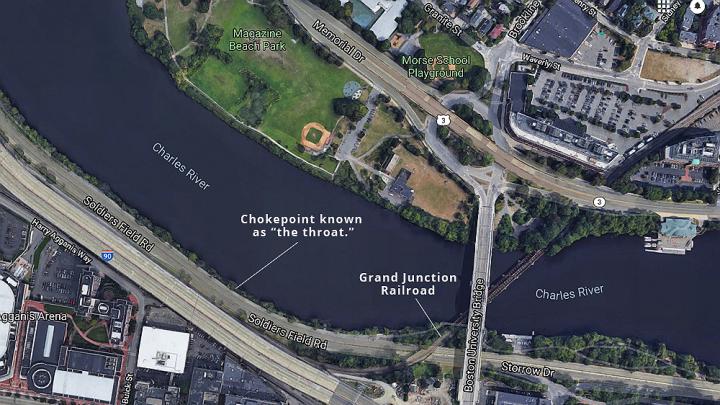

At issue for state transportation planners has been how to handle the confluence of rail lines, roadways, and a pedestrian pathway on a narrow stretch of land just upriver from the Boston University (BU) bridge—a converging choke point they call “the throat.” At the moment, a bike and pedestrian path skirts the banks of the Charles River as vehicles whizz by on the other side of a metal guardrail dividing the path from Soldiers Field Road (which becomes Storrow Drive just a stone’s throw closer to Boston). On the far side of the roadway, rail lines and siderails lie in the shadow of an elevated section of the turnpike. Officials had previously indicated that this strip of land was not wide enough to accommodate all the necessary infrastructure—the turnpike, Soldiers Field Road, the rail lines, and the path—side-by-side at ground level. Some residents had argued that the pathway could be built out over the river, as it is now (in the form of a wooden walkway that passes for a short stretch under a railroad bridge), so that everything could be built at grade. But even that solution would have been difficult to fit, and encroachment on the river would have triggered environmental reviews that could have further delayed what is already envisioned (after planning, permitting, funding, and construction) as a decade-long project.

But the difficulty of getting environmental permitting so close to the Charles River seems to have tipped the decision in a different direction: the eight-lane turnpike will now be built at ground level, while four-lane Soldiers Field Road will be elevated above the highway for a short distance as it passes through this narrow bottleneck of land. Though this solution is not cheap—the price tag is reportedly $1.1 billion for the overall project of reengineering the turnpike as it passes through Allston—building and maintaining the highway at grade will be considerably less expensive than building it on a viaduct. This design will also widen the walkway along the Charles River by about 20 feet—a welcome buffer for users of the path, who nevertheless will find themselves hard by an eight-lane highway. The additional width will also allow for the construction of new pedestrian bridges that could connect Commonwealth Avenue and the BU campus to the river. The idea of sinking Soldiers Field Road below grade along its length (once proposed as part of an unrelated Harvard campus-planning process at locations upriver by architect Rem Koolhaas, and estimated at that time to cost about $2 billion), was reportedly considered unwise due to concerns about rising sea level attributable to climate change.

A map of Harvard's land (brown) in Allston that shows the existing route of the Massachusetts Turnpike and the probable location of a future West Station. The roadway will be straightened and rebuilt at ground level.

Although Harvard was not involved in the discussions about the “throat,” it was the University’s purchase of the CSX easements—which crisscrossed the land where the turnpike will be straightened and the interchange upgraded—that has made these improvements possible. (As a public carrier, the rail line’s rights to use the land would never have been subject to an eminent domain taking by the state, for example.) In 2009, the University entered into an agreement with CSX to buy the easements in three stages of “yield up.” (Although Harvard had purchased the underlying land in the early 2000s, it could not use it until CSX “yielded up” its easement rights.) The first of these closings took place in 2015, when Harvard acquired the CSX easements to Allston Landing North, the parcel closest to its planned Enterprise Research Campus. The second, involving the purchase of CSX rights across Allston Landing South, took place in 2016. And the final acquisition, a $40-million transaction covering 12 acres near the Doubletree Hotel, occurred just last month, in December 2018.

The University is working with the state to accommodate the massive construction and planning process, including its probable plan to relocate rail lines and layover tracks for the MBTA’s commuter rail system at Beacon Park Yard. Harvard also plans to contribute at no cost the land access necessary to build the roadway. When complete a decade hence, the project will clear property the University has acquired for future academic and commercial development. The MBTA has long-term interests in the outcome of this planning process, too, because it uses the rail bridge that crosses the Charles River near the constricted location to route commuter rail cars to a repair yard north of the city, in Somerville. That stretch of track, called the Grand Junction Railroad, after passing through Kendall Square, stretches all the way to Chelsea.

Were a two-track rail line to be laid along that right of way, the state would have the option of developing a new commuter rail line that would serve an increasingly congested Kendall Square and connect it both to Allston and to points north as far as Chelsea, including potential stops at Massachusetts General Hospital, Cambridge Crossing, and North Station. If that were to occur, these trains would likely stop at West Station, a planned public transit hub on the Framingham/Worcester branch of the commuter rail, which serves Boston’s western suburbs. (Harvard and BU are hoping to bolster North-South connections by ensuring bus accomodations in addition to pedestrian and bicycle throughways.) West Station has been envisioned as a critical element in development plans for the Allston area, including Harvard’s Enterprise Research Campus (development of which may be accelerated by the recently formed Allston land company), plans for which are starting to come into focus. Last year, planning for West Station appeared to be on hold, as the state indicated that it might not be built until 2040. But after a public outcry, state leaders have indicated that this future transportation hub may be back on the drawing board, and could be built as part of the current transportation plans for Allston. The decisions about how to build the infrastructure at the throat, in other words, have far-reaching implications—for the neighborhood; for future development of a huge Harvard-controlled site near BU and potentially accessible to Kendall Square and MIT; and Greater Boston.

Asked to comment, Harvard officials stated only that “The University is pleased to see forward-moving progress by MassDOT with the selection of a preferred alternative for the ‘throat section’ design of the Allston Multimodal project. Harvard will continue to work closely with the Baker Administration, the City of Boston and the many stakeholders engaged through participation in the I-90 Task Force process on important decisions that remain.”

Secretary Pollack, whose background includes stints leading the Conservation Law Foundation and serving on the board of the Charles River Watershed Association, told the Globe that the new viaduct carrying Soldiers Field Road would be less intrusive than the existing one, and said the plan “strikes the best balance between all the different transportation objectives.”