In a seminar room on the fifth floor of the Graduate School of Design’s Gund Hall, instructor in architecture Lisa Haber-Thomson is looking over a 3-D rendering of a tall and skinny apartment complex comprised of bright red, off-kilter stacked cubes and extremely steep staircases. “Walk us through it,” Haber-Thomsen says to her student. “Do a check with yourself to make sure the circulation isn’t awkward. Imagine entering this room, and how you’d move through that space.”

Haber-Thomsen’s class is seated around the big table in the middle of the classroom shared by the College’s two architecture studio courses. Every surface is covered with materials: scraps of museum board and cardstock, partially built models, box-cutters and rulers. The room contains four televisions, a projector screen, cables strung this way and that along the ceiling, numerous rolling whiteboards with orange and green markers only, rolling tables and rolling chairs. Everything here rolls.

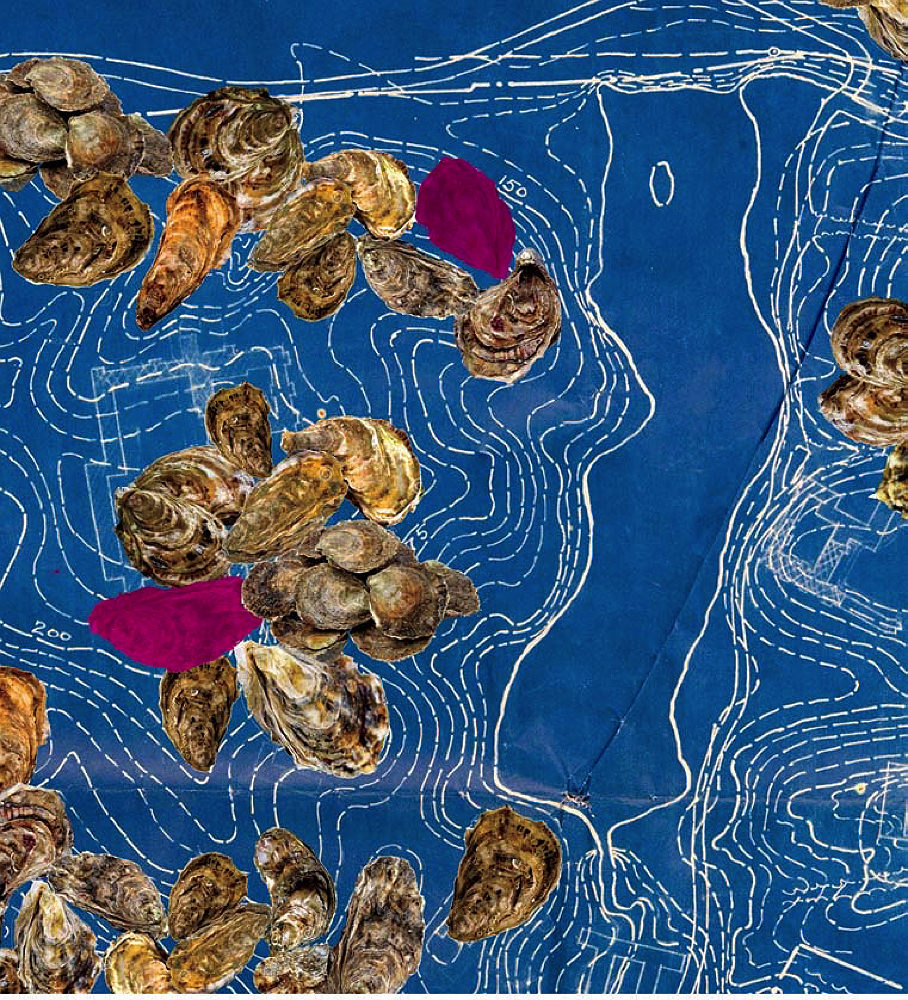

A topographical “map of the aquatic floor,” designed by Greta Wong ’18, who took the “Connections” studio in 2017

Image courtesy of Megan Panzano

The two courses—Haber-Thomsen’s “Connections,” and “Transformations,” taught by assistant professor of architecture Megan Panzano—aim to give architectural-studies concentrators their sea legs so they can hold their own in the GSD’s graduate-level courses. The architectural-studies track, a subfield within the history of art and architecture concentration, was born in 2012; Haber-Thomsen and Panzano view the program’s infancy as a strength. Rather than wrestle with a deep-seated pedagogical tradition, they can reassess at every turn how design thinking can cater to College students, and how the track can cater to the contemporary field of architecture. Their classroom can be a laboratory for testing how liberal-arts education can inform architectural-design practices, and how design thinking in turn can seep into humanistic discourse.

The track’s predecessor was the department of architectural sciences, born in 1939. Pedagogically, it gravitated around the ideas of the luminary at its center, Walter Gropius, attempting to replicate his famous Bauhaus course, “Basic Design.” Students attended lectures and built models out of clay and wire. The department had a reputation for rigorous pre-professionalism, built “essentially for men planning to go to some architectural graduate school,” as The Harvard Crimson put it in 1951. In 1968, it merged with the fledgling visual-studies program to form the current department of visual and environmental studies (VES); architecture offerings were eventually discontinued.

Today, the re-born program is wedged between the College and the GSD: institutionally affiliated with the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, but housed at the GSD and taught by GSD faculty (see “Architecture as Liberal Art,” January-February 2015). “Transformations” and “Connections” are the only practice-based offerings directed at undergraduates, and like most studio courses in VES, are oversubscribed: this spring 38 students applied for 12 spots in “Transformations.”

Sean Henry Henson ’19, who took the course this past spring, tells me the studios are difficult because students simply don’t know at first how to make the materials do what they want: there are lots of late nights cutting chipboard all wrong and fumbling one’s way through unfamiliar software. Material technologies are always changing, and with them, the limitations on what can be represented and what can be built. These courses are ambitious, expecting students to master the techniques of manipulating museum board, Plexiglas, and cardstock, wood, and chipboard, but also software for 3-D modeling and fabrication, including AutoCAD, Rhino, and the Adobe Suite. Nonetheless, undergraduates don’t need any prior skills to apply or enroll, and around half the studios’ students concentrate in other fields.

“Connections” and “Transformations” have opposite trajectories. The former begins with an assignment that asks students to consider the urban landscape from the point of view of a non-human agent, like a bird or a brick. The scope of each project shrinks, from a city to a single lot. For the final project, each student selects a site in Harvard Square to transform. A large plywood model covers four or five tables pushed together in the middle of the room. It’s a bird’s-eye view of the Square, stretching from the Charles River north to the top edge of the Yard. Everyone’s lazily resting their laptops on the outskirts. One student proposes an architectural intervention for the present site of one of the final clubs. Haber-Thomsen wants her to get a better sense of the site: “Can you get into the Fly, or whatever this is?” she asks, gesturing at what is actually the Fox Club.

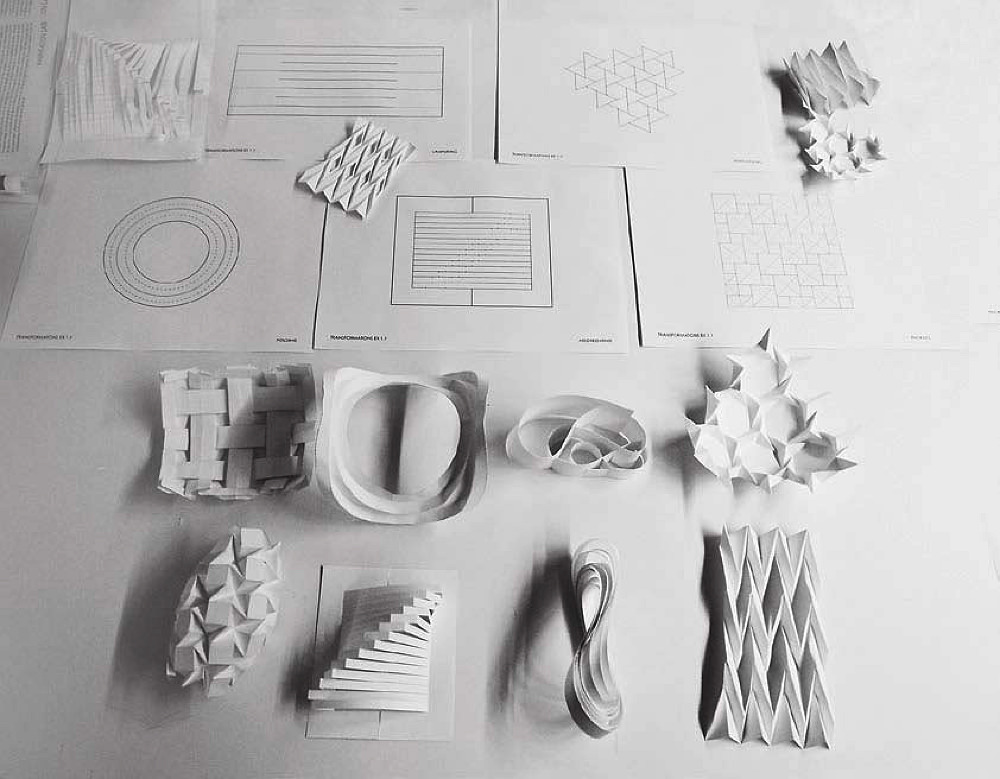

A series of paper models made in the “Transformations” studio

A series of paper models made in the “Transformations” studioImage courtesy of Megan Panzano

In her critique, Haber-Thomsen emphasizes the importance of the material expression of an idea: the materials used should reflect the flavor of what the project is trying to achieve. Her advice and attention, as she reviews projects, migrate back and forth between the idea’s form and its content. “Maybe there’s a way to start drawing your plans so that the void gets treated differently from everything else,” she says to a student working on a residential building, open to the Cambridge public, with a large atrium-like opening in the middle. She then suggests deliberately configuring the house’s communal spaces so they foster interactions between residents and visitors: placing a couch in relation to a stairwell to facilitate conversation, or placing a gallery on the top floor to encourage people to climb all the way to the top of the space.

Conversely, “Transformations” starts with individual raw materials and their capacities for architectural expression, building up to “occupiable scale.” In the first assignment, students get eight pieces of paper and eight gerunds, like laminating, folding, perforating, packing, interlocking. The goal is to manipulate each piece of two-dimensional paper into a three-dimensional form that incarnates each term. During a critique session, the class pores over the pile of more than 100 pieces of distended paper, discussing what the models are doing to the space they occupy and how they are doing it. For the second project, they zero in on a particular attribute, like the shape of a particular fold, a means of connection, or a pattern of inversion, and translate that into Plexiglas. They make a couple of models, working through this single idea again and again, trying to distort and amplify this single characteristic to see how it resonates with this new rigid and transparent material. What can you express better in Plexiglas, and what gets lost in translation?

Finally, the assignments move out of abstract space and into the real world. For the final project, each student puts a design intervention on the same site: this semester, it was Franklin Street Park, near Mather House. Henson and his classmates began by close-reading and mapping the site. Students chose to map peculiar qualities, such as the sound levels in different parts of the park, or where in the park you could be seen from outside it. Then they intervened in some way to highlight or deemphasize the chosen element, whether by adding a physical structure or manipulating the elevation or making it more kid-friendly, or, in one case, by setting up boundaries between the zones frequented by human and canine visitors. Panzano then assesses how each student’s intervention choreographs an agent’s movement through the space. How does it encourage that agent to perceive the site differently, making its hidden qualities manifest?

Both courses are organized around frequent critiques. At one of Panzano’s, she describes the students’ projects in a hyper-articulate idiom of architectural rhetoric, dense with inscrutable but delicious phrases like “typological models of space,” “element of twoness,” and “memory of the plane.” You can produce “the perception of a curve through the accretion of sharp lines.” She discusses “open systems that can be reoriented.” For one model she recommends “the introduction of material difference.” “You’ve produced hidden space!” she exclaims at one point, and then explains: if you mismatch an agent’s experience and reality, she says, you acquire the capacity to make space disappear.

As an outsider it’s hard for me to wrestle the words into meaning anything at all, but the rest of the class nods along and chimes in. They no longer need the training wheels of constant definitions. Panzano explains some of the terminology: a “datum” is a horizon-like line that tells you where a horizontal plane meets vertical ones. “Node,” meanwhile, is an example of a term that has “a particular definition in the world at large,” but “takes on a new meaning when applied to space.” A node, in architecture, is a point of change, a moment of difference, a “space of centrality,” an organizer, the place and time “where things come together.” One hears the term “attenuation,” a lot as well; it describes the “change from something that is dense to something that is less dense.” “We use a lot of terms to describe change and transition,” Panzano says.

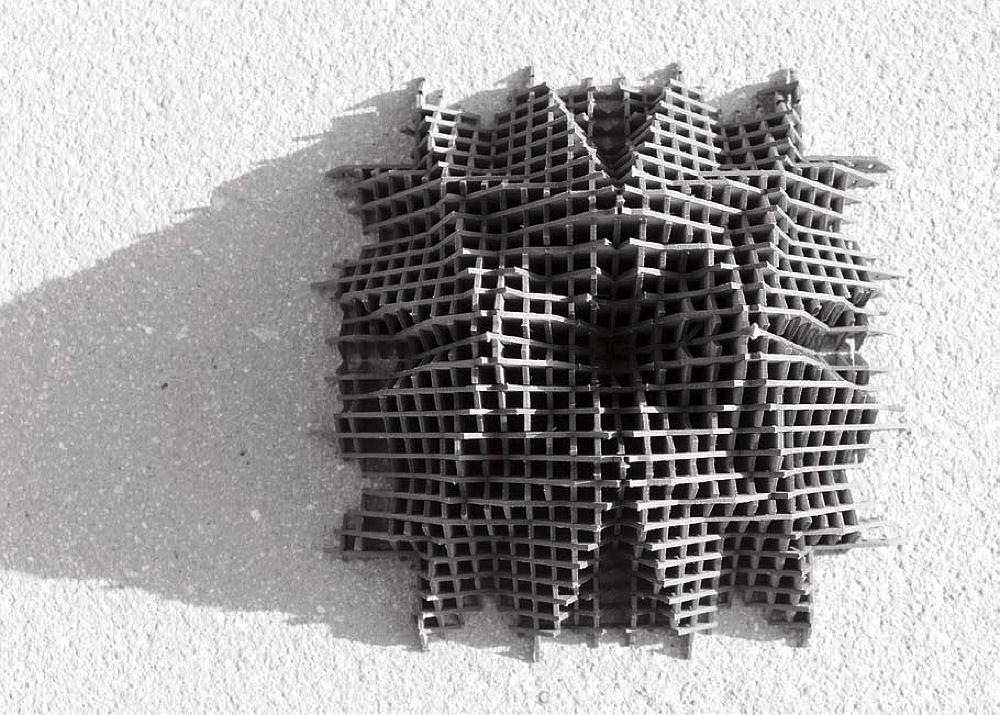

A “Transformations” model made from opaque board, exploring the concept of “intensities” through repeated, intersecting patterns

Image courtesy of Megan Panzano

Henson tells me that at first terms like “interdigitization” were incomprehensible, but he and his classmates learned to understand quickly. They also learned how to speak. Certain terms are taboo: they prefer, for example, not to use “building” to describe student projects. It’s too restrictive, implying human scale and habitability. Panzano prefers “intervention” or “assembly,” terms that defamiliarize our relationship to the urban landscape and start to dismantle clichés about architecture.

Equipped with this new vocabulary, the students can pick up on and articulate elements of each other’s projects that an outsider would never notice. In some ways the studios are really language courses: they initiate students into the design community’s lexicon, and they teach them to translate paper into Plexiglas, code into cardboard, thought into matter.

These courses are not about learning to fill up cities with livable or workable infrastructure: rather, they are rigorous training in how to think about space by handling materials, how to think through making. No other courses at Harvard transform your experience of space like these studios, a student tells me. Henson, too, feels he came out of “Transformations” with a new sensitivity to elements of the built environment around him, acutely aware of how designers manipulate the way he moves through the world.