On june 15, 1898, when Moorfield Storey, A.B. 1866, stood up to speak in Boston’s historic Faneuil Hall, the United States had just invaded the Philippines, promising the inhabitants their freedom—only to quickly renege on its word. Storey was incensed. “A war begun to win the Cubans the right to govern themselves,” he proclaimed, “should not be made an excuse for extending our sway over other alien peoples.” His speech sparked a movement that raced across the country, and he became the first president of the newly formed Anti-Imperialist League.

Born into a long-settled family, comfortable but not wealthy, Storey gained the sense of security he needed to chart an independent course. He inherited from his abolitionist mother, Elizabeth Moorfield, a tenacious adherence to the high principles that characterized his life.

The undergraduate who often skipped classes to go fishing or partied into the early hours made Phi Beta Kappa and entered Harvard Law School, only to leave in his second year to serve as private secretary to Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner, then chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He saw Sumner—widely known as “the South’s most hated foe and the Negro’s greatest friend”—as “a man of absolute fidelity to principle and…unflinching courage,” and his mentor’s influence proved pivotal for the remainder of his life.

Even so, Storey became “a dangerous example of frivolity” in Washington, wrote Henry Adams, A.B. 1858. Near the end of his stay he met a Southern belle, Gertrude Cutts. “We danced together well and we did it whenever opportunity offered,” Storey wrote later. Though he told her father, “I was not a lawyer, I had no money and no expectation of money,” his future father-in-law was “very gracious and kind”; the couple were happily married for 40 years. But Storey now had his living to make and “reverted to the law,” dropping thoughts of a political career.

Despite a full professional life, Storey felt a sense of noblesse oblige; he also favored Abraham Lincoln’s remark that “those who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves.” At the time, major European powers were carving out colonies in Africa and Asia, while the United States in nine months had brought Cuba under military rule and annexed Puerto Rico, Guam, Hawaii, and the Philippines. Besides leading the Anti-Imperialist League, Storey published articles and speeches against imperialism, sent a steady stream of letters to newspaper editors, and corresponded heavily with prominent officials. He campaigned vigorously for the rights of fellow citizens as well. In words that still ring true he declared, “One of the greatest dangers which threatens this country today is racial prejudice and it should be the duty of every person with any influence to discourage it….” His championship of indigenous peoples led him to advocate for the rights of Native Americans, who he felt had been badly mistreated by the U.S. government. And in particular, he put his legal talents to work on behalf of black Americans.

He was one of the prominent, mostly white, Americans who gathered, six months after a bloody race riot in Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield, Illinois, and founded the NAACP in February 1909; in 1910 he was named its president, a post he held until his death. As a former American Bar Association (ABA) president and noted constitutional lawyer, he contributed prestige and hard work to the new group as its legal counsel. In 1913, the NAACP filed its first brief, in Guinn v. United States, a case before the U.S. Supreme Court challenging the legitimacy of the so-called grandfather clause—a statutory provision in some Southern states that disenfranchised black voters by specifying that men whose grandfathers were not voters before the Civil War could not themselves vote. The court ruled in 1915 that such a clause was unconstitutional. In another Supreme Court case, Buchanan v. Warley, Storey gained a unanimous verdict declaring unconstitutional all ordinances or laws limiting the right of citizens to purchase or occupy property in any section of a town, city, or state. He also prevailed in the so-called Arkansas Cases, in which 12 black men were found guilty of murder and some 60 others of riot or manslaughter; the Supreme Court ruled that the men had not been given a fair trial. A silver cup presented to him in 1918 by black New Englanders called him “a renowned Advocate and gallant Defender of the civil and political rights and equality of American citizens.”

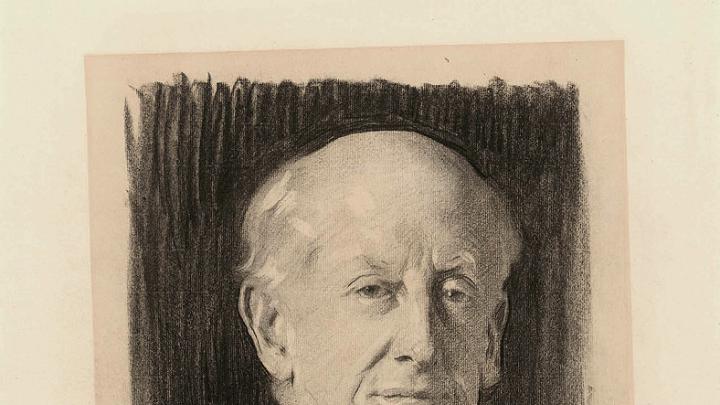

Storey was not averse to controversy, and even seemed to thrive on it: the National Portrait Gallery states that he himself joked that some considered the portrait opposite “a fraud on the public, since it represents such an amiable old gentleman instead of a ferocious bruiser.” He opened the ABA to black lawyers by threatening to resign as president, and as a Harvard Overseer (serving 29 years in all), he led a group that sought to force the University to admit black students to its dormitories. (President Lowell feared the measure would discourage Southeners from applying.) He further courted unpopularity, and perhaps lost an honorary degree, by arguing that football glorified physical force and combat and should not be allowed.

Yet his biographer, M.A. DeWolfe Howe, also wrote of “the warmth of his affections, the tenderness of their display in all his relations with family and friends….” Perhaps he followed the advice of Polonius to Laertes: “To thine own self be true…Thou canst not then be false to any man.” He did not believe in an afterlife, but—like his mentor, Sumner—must have been pleased at having helped to lay down a foundation for future progress in civil rights.