It is a Harvard tradition never to announce in advance who will receive honorary degrees at Commencement. It’s also a tradition to honor the reunion-class marshals after the morning exercises by having them escort the honorands during a reception, a lunch, and a tour of the campus, and finally to the Commencement day afternoon exercises. As First Marshal of the College class of 1965 for a quarter-century, I was offered that opportunity in 1990 and gladly accepted. I was not told who the honorand would be until I arrived in Cambridge on the day of the event, when I learned it was theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking. The other honorands included Helmut Kohl and Ella Fitzgerald. I may have been paired with Hawking because I was a physician/scientist and the Commencement planners thought I could better connect with him than others could. It would turn out to be a life-saving decision.

The event planners had prepared a large three-ring binder on Hawking for me, and I was told to read it so I would better know the man. In addition, I was told that two small spaces on campus had been set up with medical equipment if “needed.”

If “needed,” I thought? Needed for what? I quickly committed their locations to memory.

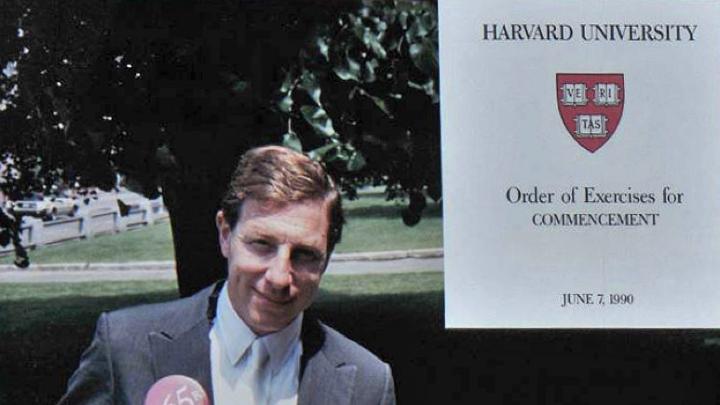

I dressed in the required clothes: cutaway formal, vest, white tie, and black silk top hat. I was also given a white and crimson “wand”—a 16-inch wooden rod that is traditionally carried (and waved, to direct traffic) on Commencement day by class officers. I had carried one at my own Commencement 25 years earlier, and it held special memories for me.

Hawking had just published his first book, A Brief History of Time, and had flown to Boston overnight from California, where he had met with Steven Spielberg and discussed a movie to be based on that book. I was told that the batteries controlling his breathing machine—he had had a tracheotomy years before—were low. I stored that information away.

After going through a metal detector supervised by the Secret Service (because Kohl, then prime minister of the about-to-be-reunified Germany, was also at the lunch and reception), I was introduced to Hawking. I called him Dr. Hawking and he called me Dr. Abramson. He was unable to speak, but could communicate using a voice synthesizer controlled by just one of his fingers. The first thing he did was apologize for his “voice,” which had a generically Midwestern American accent. I sensed that he wished I could hear his real voice—but I was to learn that was only one of the many compromises he had to live with because of his disease—so we moved on.

My first task was helping him sign a large, leather-bound volume signed by many of those who’d previously received honorary degrees from Harvard. Hawking had anticipated this, and his team of helpers had brought a pad (a very worn-out pad that didn't quite close, so the inked part had dried out) that enabled him to leave his fingerprint in the book. It turned out that Harvard, recognizing the need for such an inkpad, had also supplied one. As the ink was cleaned off his finger, Hawking gave me a look and I understood what he was thinking; I left his old pad for Harvard and he retained the new one. He moved his wheelchair away after the transfer and said, “Thanks, and now call me Stephen.” From then on, he was Stephen, though I was still Dr. Abramson.

The reception lasted about 25 minutes. I wondered how to start a conversation. I started by mentioning that I had read his book recently, and told him that as an undergraduate I had studied physics, including relativity and quantum mechanics, so I understood most (but not all) of what he had written. I asked why he had chosen to write a book on the origin of the universe and relativity without mathematical formulae—there is only one: E=mc2—and speculated that perhaps he thought it would bring about world peace or a better understanding of the common origins of all people on earth. To answer, he had to use his single finger to access letters, words, and phrases saved in the synthesizer’s computer, so while his mind reacted quickly, his “voice” didn’t. Eventually it said, “I needed the money,” and added, “Why else would you write a book?” He then explained that as his ALS progressed, he needed more assistance and had applied to the British National Health Service for 24/7 care. They had replied that he could have 24/5 care. He needed to cover the costs of the additional two days or, as he said, “I would live exactly five days and die.” So much for world peace.

I tried another subject. I mentioned that I had looked through a friend’s relatively high-powered telescope twice at night. I could identify some planets and classic constellations but little else. I asked if he had ever looked through a telescope, wondering whether such an experience was the origin of his quest for the history of time, or perhaps had stimulated him to envision black holes and space-time warp. I imagined him as a child sitting under a tree at night being transfixed by what he was seeing. He replied that he had indeed looked through a telescope (only once), and that all he saw were white dots that meant nothing to him at all. He never wanted to view them again through a telescope, he said. To him the origin of our solar system and the space-time paradox was a mathematical puzzle better envisioned by formulae than by star-gazing.

Lunch was served, and Helmut Kohl, Ella Fitzgerald, and my fellow marshals sat at our table. Stephen was on my left and Kohl on my right. As per tradition, each of the honorands stood up and addressed the audience. Ella Fitzgerald sang. Stephen turned his wheelchair to face her, and then told me she was his favorite singer of all time and that had been the high point of the Harvard visit so far. Kohl also stood up to speak. Because Stephen was no longer facing him, I asked if he wanted me to turn his wheelchair around so he could face Kohl. He blurted out, “Why would I want to listen to that man?” Everyone (including Kohl) heard that. I remembered a line from that three-ring binder: “Dr. Hawking has strong feelings about some issues and often expresses them.”

We left the luncheon and strolled around Harvard Yard together and then went to a receiving line where students, faculty, families, and graduates could “meet and greet” the honorands before the actual afternoon exercises. I stood behind Stephen as hundreds of people walked by. I thought this would be a wonderful opportunity for him. It wasn’t. Yes, a few graduate students came up to ask detailed scientific questions and each waited while he painstakingly replied. Most people asked a question and, when he didn’t respond immediately—which was impossible (it could take 20 seconds to reply)—simply walked away. I was embarrassed, and then appalled when others walked by, pointed at him, and said, “What a funny-looking man.” Here was one of the world’s greatest minds, a teacher to millions, an emblem of human strength and dignity, and all they saw was a “funny-looking man.” I was relieved when we joined the formal procession and went on stage for the ceremony.

The afternoon exercises are long and it was extremely hot that day. To save the battery, Stephen turned off his synthesizer because he knew he would not be “speaking” for a few hours. I sat behind him but positioned myself so I could watch his breathing. About 20 minutes into the ceremony (being broadcast live on TV), I noticed that his chest was not moving and his color was rapidly changing. Though I was not able to identify all those white dots in the nighttime sky with a telescope, I knew exactly what was going on medically. Stephen could not move or “talk,” and with his synthesizer off he couldn’t even send a message that he was in trouble. I immediately saw a headline in my mind—“Stephen Hawking dies at the Harvard Commencement”—but my medical training instinctively allowed me to react quickly. I stood up, grabbed his wheelchair, turned him around, and pushed him past the dignitaries and off the stage. (A ramp had been constructed for him.) His nurse followed.

I remembered that Harvard had left some supplies in a room nearby so we pushed him there…and discovered that it was also the temporary headquarters of the Secret Service. I quickly learned that you don’t rush full speed into a Secret Service headquarters. For a few seconds I think the agents thought I was a crazed terrorist, and I did see weapons, but quickly they recognized what was happening. His nurse and I realized that his tracheotomy was clogged and that was why he was not breathing. Thanks to the medical supplies at hand we were able to get him breathing again. Yes, he would have died.

We wheeled him back to the podium (the program had not stopped—no one except my wife seemed to have thought anything was awry), and after the ceremony I escorted him to his van, where I said good-bye…and took a very deep breath as the van drove away. I had started walking back to the Yard when I heard the van screech to a halt. An aide jumped out and came running toward me. I thought the worst. Perhaps the headline was going to be “Stephen Hawking dies just after the Harvard Commencement.”

The aide said that Stephen had asked me for my “wand.” He wanted to put his fingerprint on it to thank me for saving his life. I gave it to the aide and he returned a few minutes later with the wand and the fingerprint on it. He said Stephen had told him to tell me that he “used the new ink pad,” although the aide said he didn’t know what that meant.

I smiled and walked out of Harvard Yard…waving the wand proudly and holding only the edges, so as not to disturb his fingerprint.