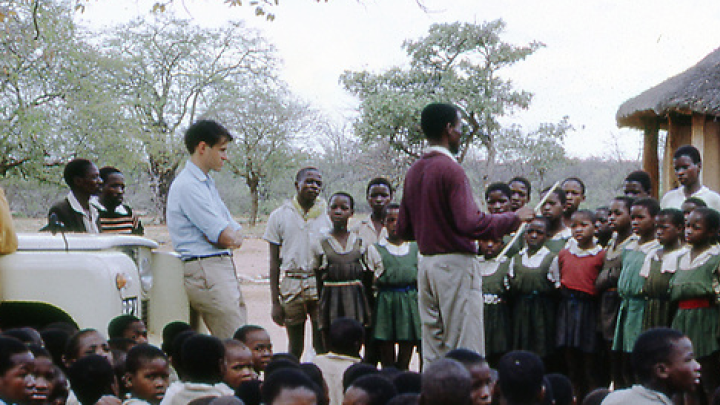

APPROACHING HIS FIFTIETH REUNION, the author, class of ’68, engages the ghost of his great-grandfather, Edward (Ned) Hooper, A.B. 1859, LL.B. ’61 (and subsequently Treasurer of Harvard College from 1876 to 1898 and LL.D. ’99), about the surprising similarities in their respective experiences in the Peace Corps and the Civil War, many of which occurred in the very same spot in the South Carolina Sea Islands. Hooper arrived as part of a group of “missionary” volunteers from Northern abolitionist societies to “do good” for the 11,000 former slaves on these islands who remained on their respective plantations when their white owners and overseers fled from the U.S. Navy. Though soon given a captain’s commission in the occupying Union army, Hooper remained focused on the missionaries’ efforts to provide education and agricultural development assistance to the former slaves. The author, arriving a century later, interacted with language instructors from Africa and local African Americans as part of Peace Corps training for an assignment involving an educational project in Africa. An edited excerpt from a longer account of their encounter follows; readers may request the full account, “Ghost Story: Two Encounters Between Race and Idealism in the American South and Beyond” (2016), from the author at mknapp@uw.edu.

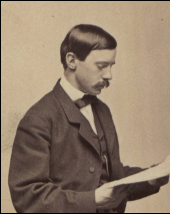

A detail from a Civil War era photograph of an out-of-uniform Ned Hooper

Courtesy of Michael S. Knapp

Here, my great-grandfather’s ghost whispers in my ear: How well prepared were you Peace Corp volunteers for your upcoming projects? My answer: Not well. And who were you and what did you bring to this enterprise? Not much, beyond youthful enthusiasm and high ideals, as well as whatever mental discipline and common sense follows from 16 years of schooling. To be sure, we had some useful experience (e.g., tutoring, social-service volunteer work, advocacy work) to back it up. And racial justice was our gospel, probably as much as for Ned’s abolitionist mates. We came of age in the swirl of the 1960s and the civil-rights movement; we knew the words to “We Shall Overcome.” What we lacked in practical know-how, we made up for (or tried to) in our determination to advance a more racially and socially just world. And, in true abolitionist fashion, we were intolerant of intolerant people, specifically, those opposing the advancement of black people.

Ned’s fellow missionaries were equally well educated, and just as idealistic as we were. Many came from well-off families in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, and all had been immersed in one or another church-based abolitionist movement in the years leading up to the Civil War. When the call came for people to help former slaves in the Sea Islands, their response was instantaneous. But their knowledge of the South, cotton growing, and pedagogy was limited or nonexistent.

Whatever Ned or I brought to our respective volunteer roles, none of it prepared us for meeting another culture. “I knew nothing of the Negro character,” his ghost says. On first encounters, the missionaries found their initial assumptions tested and stretched (as well as in some ways confirmed). The former slaves they met were welcoming, if sometimes wary of the new white faces they were now interacting with.They were especially open to schooling, and responded enthusiastically as the missionary men and women introduced them to reading and writing, activities strictly prohibited by law in South Carolina for many decades prior to the Civil War. Though a few former slaves had learned to read (surreptitiously and at great danger to themselves and their teachers), most were illiterate. Virtually all, however, sensed the value in written communication and, no matter how old, crowded into the missionaries’ classrooms, wherever these were organized. As one of Ned Hooper’s fellow missionaries put it, “[the former slaves] had seen the magic of a scrap of writing sent from a master to an overseer, and they were eager to share such power, if they were given any chance.”

Nonetheless, the two groups struggled to make sense of each other. The former slaves’ actual interactions with the missionaries typically mimicked what they had done with their plantation masters’ families, despite the absence of physical coercion. How else to understand educated, well-off white people? How else to behave toward them, but through a mixture of docility, friendliness, cunning, deception, and wariness? The ordering of relations between whites and blacks had been clear and understood under the old plantation arrangements, as Hooper found out one day to his surprise: when he gave his comfortable seat in the front of a carriage bound for church to an elderly black woman, and took a seat in the back, the black coachman was incensed and protested loudly.

My great-grandfather’s ghost wonders: What about your early encounters with black people? Were they all that different from mine? In fact, the differences were striking. Our African instructors were educated people from another continent, helping us learn their languages. The African Americans living and working in or around the community center where we were staying, half of them veterans of the civil-rights movement, gave us a glimpse of articulate, independent leaders in action. Yet we met the other members of the local community with varying degrees of awkwardness, only scratching the surface of relationships that crossed huge differences in outlook and experience. I remember my discomfort at being treated with undue respect and deference by several older African-American men, no doubt reflecting habits learned under Jim Crow. I also recall groping for things to say to a black man who, during my weekend stay with his family as part of Peace Corps training, drove me around the nearby Marine Corps training base at Parris Island where he worked as a janitor. He was proud of the base and his work, and I, flush with antiwar sentiments so widely held within my student community, hesitated to share those with him. And I remember standing in an awkward knot of Peace Corps volunteers at a community dance, not quite daring to ask several attractive young black women to dance. Natural shyness, compounded by who knows what reservations we and they had all grown up with, prevailed. As in Ned’s time, we and our counterparts in the Sea Island community slipped into the familiar roles and assumptions of a segregated society, more than we ever admitted….

BEYOND FIRST ENCOUNTERS with strange cultures during our weeks and months in new social surroundings, my great-grandfather’s story and mine diverged, as he and his missionary colleagues hunkered down for the duration of the war, while I headed off to wage peace on another continent. Still, the parallels were unmistakable. Overt racism among the other white people we dealt with, for one thing (“They’re just out of the trees,” one British expatriate with whom we worked proclaimed). The lack of guidance, for another.

Did anyone tell or show you how to do the work? my great-grandfather’s ghost wonders. In his case, no one knew what it meant for 11,000 former slaves to suddenly be freed from a slavery-based system of labor and living. There was no national or local precedent or law that indicated how to proceed. How to organize a cotton-farming system, in which former slaves were not compelled to work, yet which drew on their energy and intimate knowledge of local conditions? Could former slaves be given the land they had farmed for generations, now that the white planters had left, or should they be asked to buy it, albeit at reduced rates? Captain Hooper and his commanding general spent endless hours improvising answers to these questions, as did the missionaries assigned to the different plantations as agricultural supervisors. They made it up as they went along.

We Peace Corps volunteers did a lot of improvising, too. A little too much in Botswana, it turned out, when we confronted our expatriate superiors in the training college we were assigned to about the shortcomings of their teacher-training curriculum and their apparently racist assumptions about the teacher trainees.Our response to this situation was to write up a stinging, critical report, leave it on our dean’s desk, and take the next train (two hours later) to Gaborone. The upshot: we were asked to leave the country a few weeks later. So much for changing the system. The Peace Corps relocated me to Malawi, in south central Africa, to join a curriculum center that was developing inquiry-oriented science units for African elementary schools. There, a sudden decree from the country’s dictatorial president—that the center inaugurate science education in all 2,000 of “his” schools…by the start of the next school year (eight months later)—plunged us into improvisation on a grand scale: no small feat for a tiny outfit that had piloted only two dozen hands-on science units in several dozen schools. No one was there who could show us how, but we found a way, unbelievably.

Ned’s ghost nods. It is all too familiar—the sudden decrees from on high (whether from a dictator, military commandant, or the federal War Department), the impossibility of effecting substantial changes in thinking and practice at hundreds or thousands of sites, the critical shortages of key resources at the most inopportune times—all of it in a forcefield populated by actors with other agendas on their minds. And just as familiar, the central actors, who must ultimately carry out the change (in pedagogical or agricultural practice), were ill-prepared for the new work, due to limitations imposed by generations of slave status or colonial domination….

My great-grandfather’s ghost has one more thing to ask about. How are things a hundred years later? Have things improved for black people since then? And he adds: Was what we did helpful? Ned died in 1901, well aware of the turn that the South had taken toward Jim Crow. He knew that the missionaries’ efforts, for all their failings, had demonstrated former slaves’ capability and eagerness to learn, capacity to be productive independent farmers, readiness to step into the role of citizen as Reconstruction started. But he had seen (from a distance) the backlash and the descent of the South into patterns of living that were only marginally better than the old slave system, if that.

I answer in two ways. As of the late 1960s, a vigorous civil-rights movement confronted segregation, and laid a foundation for many changes that promised to enhance racial justice. I tell him of the competent and (somewhat) empowered African-American leadership I met or heard from there and elsewhere. I review for him national laws passed and judicial decisions that secured voting rights, more equal opportunities in education and employment, and other advances, though it took the full century since his own time to realize these gains—and they were achieved against massive, deeply entrenched resistance. But I affirm that, by the end of the 1960s, these were the laws of the land, and there was widespread support for them.

Then I speak about the state of things a half-century later, in the 2010s. Further advances have been made, I assert, not the least of which are the fact of an African-American president, the growth of an educated black middle class, and substantial gains for many in education and employment. I note a gradually more welcoming social climate, especially among younger people. But I mince no words on the precarious state of race relations in present-day America, if not the world, and the continuing manifestations of institutional racism that are so obvious. I tell him about the “new Jim Crow,” about how the treatment of black people by police has prompted the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. I note the election of a white president with little regard for people of color, and the growing legitimacy of white supremacist groups and thinking. I speak about the disparities in housing, health outcomes, and other measures of social welfare. And about the meanings of the “colorblind” society, which so systematically fails to see, or care about, the situation that many African Americans find themselves in.

Did our efforts in the Sea Islands and the Peace Corps make a difference in any of that? Not much, I say. We changed some hearts and minds among the people with whom we worked, for sure (though we were surely changed far more). We enabled some to achieve new possibilities for their lives. But we were far from a potent force for the systemic changes that were needed. My great-grandfather’s ghost nods. He knew, or might have guessed. He adds that we’ll probably both be ghosts when the fundamental changes ultimately transpire. Something to look forward to. Something worth working toward, if only to keep the idea alive.

I close with a comment about what he and I were in these stories of social upheaval. Agents of actual changes? Not really. Catalysts, perhaps; saviors, no. I think we went in assuming we could reshape the landscape of reform, and along the way save some souls. Both of us thought that because we were educated, empowered, and white, we had education, empowerment, and privilege to bestow. Not really. We came away humbler and with the beginning recognition that our own souls could use some saving, too. At a minimum, the edifice of white privilege needed far more dismantling than we had managed or imagined. But I, at least, came away with some hope for the future, however many lifetimes that may require….