Eunice Kennedy arrived at Radcliffe in November 1943 with a lingering British accent and a fading California suntan, remnants of her convent school days in London and her more recent undergraduate studies at Stanford.

The fifth of the nine children of Rose and Joseph Kennedy ’12 came to Cambridge to complete the last few credits of her Stanford degree under the watchful eyes of her mother and father, the former U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, then on Cape Cod raising vegetables and beef cattle on a farm in Osterville. “We finally had Eunice transferred,” Rose wrote her other children that fall. “I am very happy about it as…Radcliffe does not begin until the first of November [because of Harvard’s wartime schedule] so she has an extra month with the farm food.”

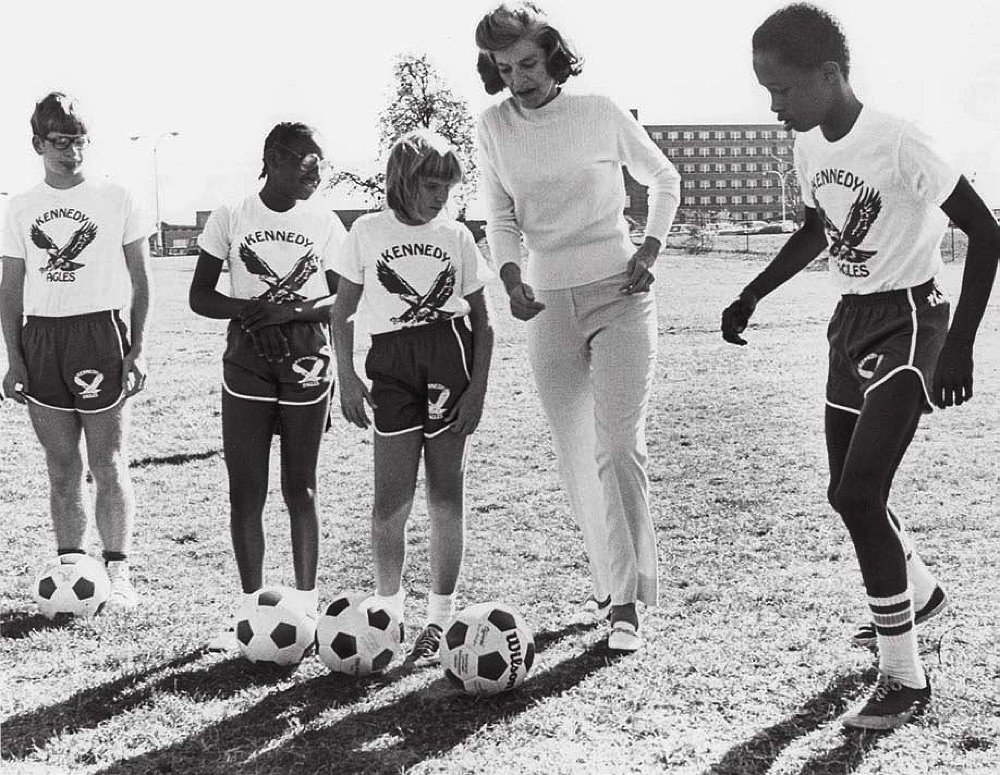

Woman in action: Shriver engaging young athletes in Ireland

Photograph courtesy of the Special Olympics

Like her older brother Jack, who had graduated from Harvard in 1940, Eunice was plagued by digestive and stomach problems. Within a few years, both would be diagnosed with Addison’s disease and placed on a regimen of corticosteroids to compensate for malfunctioning adrenal glands. When Eunice arrived at Radcliffe, she stood five-foot-ten and weighed only 109 pounds, so skinny that her siblings called her Puny Eunie and her father cautioned her to prioritize meal time over study time.

It is a directive one cannot imagine him giving the equally scrawny Jack. “If that girl had been born with balls, she would have been a hell of a politician,” Joe Kennedy once said of Eunice, his absence of ambition for his best-educated daughter less a reflection of her abilities than of his lack of imagination. Born only a year after American women secured the right to vote, Eunice came of age a generation before the second wave of feminism expanded expectations and opportunities for women. In many ways her struggle to be seen—on the public stage and in her own family—mirrors the experience of the many women in mid-twentieth-century America who had to maneuver around the rigid gender roles that defined the era.

Nowhere were those roles more deeply ingrained than in the Kennedy family. Of the three sisters not lost early to tragedy, only Eunice broke out of the box to which her gender consigned her, finding her way around her father to secure her place in history.

Appearance to the contrary, there was nothing frail about the thin young woman who threw herself into campus life on the Radcliffe Quad. She studied classical music, conceding to her parents that, although she was “no Chopin, I think I know him better than he ever knew himself.” She introduced to the Catholic Club the Reverend James Keller, a Maryknoll priest who would become a popular radio and TV personality. She took charge of the British booth at a campus benefit for Allied troops, telling her mother, “I think the Kennedys are becoming more British than the British themselves.”

And she was becoming as much a Kennedy as any of her brothers, excelling in athletics, the one arena where skill trumped gender in her male-dominated family. She was the best sailor in a group of natural mariners, the best tennis player among siblings who had volleyed on the grass courts of Wimbledon. Trained by her father not to lose, she rarely did. But Eunice would turn on its head Joe Kennedy’s dictum that first place is the only finish that counts.

Two years before she arrived at Radcliffe, Joe had authorized the lobotomy of Rosemary, his eldest daughter, who had been born with intellectual disabilities. Eunice, three years younger, had been Rosemary’s closest companion, teaching her to swim and sail and traveling with her as teenagers on their first tour of Europe. The experimental surgery left Rosemary unable to walk or talk, exiled to a Catholic nursing home in Wisconsin by the patriarch’s decree.

It is uncertain when Eunice learned what had happened to Rosemary, but her sister’s plight clearly inspired her life work. In 1968, she opened the first Special Olympics, welcoming 1,000 athletes with intellectual disabilities onto Chicago’s Soldier Field just as she and her husband, R. Sargent Shriver, the first director of the Peace Corps, had welcomed 100 children with similar disabilities to a makeshift sports camp on their Maryland estate yearly since 1962.

…and in the United States

Photograph courtesy of the Special Olympics

In Eunice Kennedy Shriver’s refusal to accept her physical limitations or her father’s limited expectations, the seeds of more than the Special Olympics were sown. The same willful determination would chart her course for a half-century on behalf of those with intellectual disabilities who were denied a place on the playing field, a chair in the classroom, or a job in the workforce.

Ironically, it was also from Joe Kennedy that she learned how best to advance that cause. “It’s not what you are, it’s what people think you are,” counseled the man who, in one generation, recast the Kennedys from Irish-American strivers into American royalty. Social acceptance, of a Catholic president or a child with intellectual disabilities, first required a change in public perception.

Eunice engineered that in 1962, when she invited photographers from The Saturday Evening Post to capture images of children on rope swings and in the swimming pool of her backyard; in 1968, when she recruited professional athletes as their coaches; and in 1972, when she convinced ABC’s Wide World of Sports to televise their games.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver changed the world. This year, the fiftieth anniversary of the first Special Olympics International Games, more than five million athletes are participating in 100,000 competitions in 172 countries. That’s a legacy at least as profound as any left by her more celebrated brothers.