Beauport, perched on Gloucester’s Eastern Point, is much more than a beautiful house. Touring its maze of rooms offers a romantic exploration of literary and historical themes through decorative arts. It’s also a trip into the artistry of Henry Davis Sleeper, one of the country’s first professional interior designers. “Beauport feels as though he just walked out the door, even though he died in 1934,” says Martha Van Koevering, site manager with Historic New England, which owns the property (also known as the Sleeper-McCann House). “It’s a very personal place, his own creation. The whole composition is a work of art.”

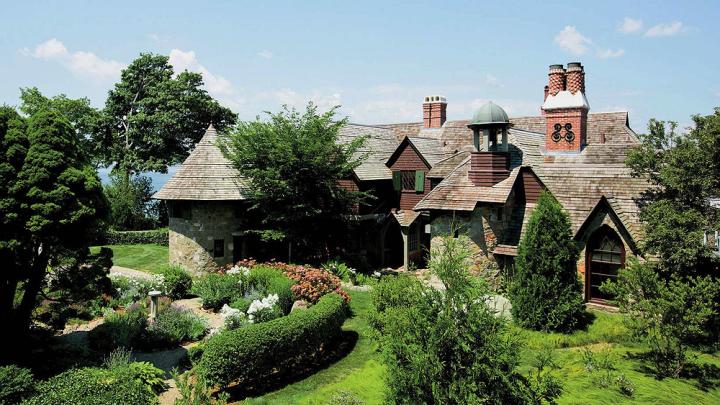

Beauport’s charm begins with lush gardens of perennial flowers and coastal grasses, and a rear brick terrace overlooking Gloucester Harbor. The home’s fairy-tale exterior—pitched rooflines, tower, belfry, diamond-paned leaded-glass windows, and chimneys are an amalgam of Arts and Crafts, Gothic, medieval, and early Colonial architecture.

The interior is just as eclectic. Sleeper originally built a modest Arts and Crafts-style cottage, but expanded it slowly during the years he summered there. The resulting 40 rooms (26 of which are shown on daily guided tours) are mostly packed together like a warren, with alcoves, odd-angled rafters, and linking stairways. And everywhere, exquisitely displayed, are the more than 10,000 objects and furnishings that Sleeper acquired, with special fondness for salvaged architectural artifacts.

A portrait of the pioneering interior designer Henry David Sleeper

Courtesy of Historic New England

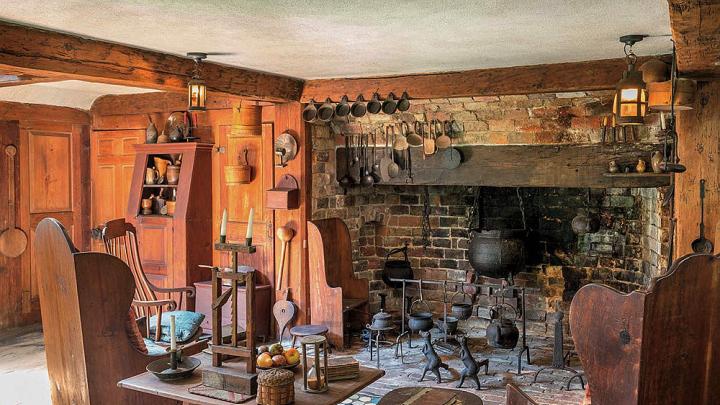

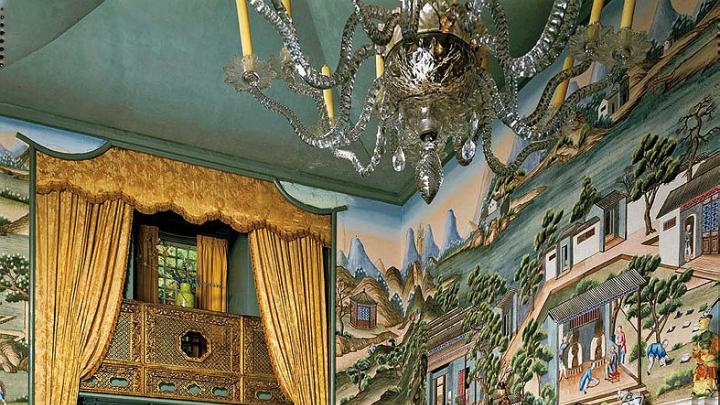

Each space is a meticulous stage set with a specific theme. A two-story book tower, with a balcony and arched windows, was designed around antique carved wooden curtains that Sleeper had found. Three early bedrooms pay homage to English figures: Lord Byron, naval hero Horatio Nelson, and the Gothic novelist Horace Walpole. The “China Trade” room, with its soaring ceiling, features a pagoda-inspired gold-curtained balcony, a marble fireplace, and bold antique 1780s wallpaper (originally ordered by Robert Morris, a signer of the Declaration of Independence) depicting the rice and porcelain industries of China. There’s also a Jacobean-style dining room with a wood-beamed and white-plaster ceiling and heavy oak furnishings that feels like an old English pub. “Yet he wasn’t a stickler for pure authenticity,” Van Koevering says. “The ‘Pine Kitchen,’ one of the later rooms, is Sleeper’s romanticized view of a Colonial-era kitchen.” It has a wide brick hearth hung with antique cast-iron pots and utensils, but he had a local furniture-maker create the simple wooden chairs, which are “a little different from what the Colonials would have had, and a little more comfortable. So he would break the rules sometimes.”

He also freely repurposed historic materials: Beauport’s central hall is lined with pine paneling (rescued from the dilapidated eighteenth-century William Cogswell estate in nearby Essex); from the hall one can also see the bulk of one wall filled with a graceful double-wide, leaded-glass door, obtained from a home in Connecticut, that Sleeper altered to hold his perfectly arranged 130-piece collection of amber-glass objects. He cleverly installed a skylight in the pantry behind the door “so that the amber is always naturally back-lit,” Van Koevering notes. Nothing was collected in the name of investment. “He deliberately selected only objects that personally appealed to him, in as much as he didn’t have the deep pockets of other collectors in Boston at that time,” she says. “And he had this fabulous ability to showcase things.”

Sleeper’s light-filled “Golden Step” room, holding a bank of diamond-paned windows overlooking Gloucester Harbor, is a nod to New England’s maritime history. Woodwork, the trestle tables and chairs, and a cabinet painted a sea-foam green set off majolica and Wedgwood dishware. Prow ornaments of bare-chested mermen hang on the wall amid models of a China trading vessel and whaling and fishing ships.

Adjacent is the “Octagon Room.” Aubergine walls dramatize Sleeper’s amethyst and ruby-red glassware and red antique toleware (tin objects, typically kitchenware) that he brought home from France. Visitors can hunt for the groups of “eights”: hooked rugs, chairs, sides of the table, scores in the ceiling, and even facets on the door knobs, Van Koevering points out. So excited was Sleeper about creating this space that in 1921 he wrote of his plans to his friend, the art patron Isabella Stewart Gardner (of the eponymous Boston museum), “Of course, I have all the details visualized and am enjoying it accordingly.”

Gardner visited Beauport many times, as did other prominent members of Boston and New York society and art circles; Eastern Point itself was developed at the turn of the twentieth century as a wealthy summer enclave (which it still is). Yet the residents, at least those Sleeper socialized with, tended to be the less conventional members of the elite, more “bohemian-minded” and intellectual.

Abram Piatt Andrew

Public Domain

Sleeper himself came from a Boston family of comfortable means: his father, Jacob Henry Sleeper, was a revered Civil War veteran, and his grandfather, Jacob Sleeper, a founder of Boston University. Reportedly frail, the young Sleeper was presumably tutored at home, Van Koevering says, but no record of any formal education exists.

In 1906, as a 28-year-old bachelor, he was introduced to Eastern Point by Abram Piatt Andrew, Ph.D. 1900. An economics professor at Harvard, Andrew served as director of the U.S. Mint in 1909 and 1910 and played a role in the creation of the Federal Reserve System. Also a bachelor, he had already built his own summer home, Red Roof, on Eastern Point’s rocky ledge. Enamored of the site’s beauty and “clearly besotted” with Andrew, Van Koevering says, Sleeper purchased a lot one house away, and by 1908 had moved into Beauport, named for French explorer Samuel de Champlain’s description of Gloucester Harbor. The two men became close, and years later during World War I, when Andrew founded the American Field Service, an organization of volunteer American ambulance drivers who worked on the front lines in France, Sleeper served as its administrator and fundraiser both in Boston and in Paris.

The "Octagon Room" at Beauport

Photograph by Eric Roth/Courtesy of Historic New England

Sleeper's summer home sits on Eastern Point, with views of Gloucester Harbor.

Photograph by Eric Roth/Courtesy of Historic New England

Beauport's "Golden Step" room celebrates maritime history and culture.

Photograph by Eric Roth/Courtesy of Historic New England

Beauport's verdant grounds

Photograph by Eric Roth/Courtesy of Historic New England

Sleeper's cleverly back-lit display of amber glass

Photograph by Eric Roth/Courtesy of Historic New England

That “besotted” assertion is based on 60 extant letters he wrote to Andrew between 1906 and 1915. There is no explicit proof the men were gay, or that they had a romantic or sexual relationship. (Sleeper’s personal papers might have contained evidence of his preferences, but those items, although listed in inventories of Beauport’s holdings following his death, were missing by the time the mansion was opened to the public in 1942.) Yet, about a decade ago, after a close friend of Sleeper’s identified him as gay in an oral history, Van Koevering says, Historic New England began acknowledging that idea during its tours. The organization also encourages discussions on the subject. “A Celebration of Pride and History at Beauport Museum” (on June 10) highlights “the story of a gay man in the early twentieth century,” according to the promotional blurb, and explores Sleeper’s circle of family and friends. And on June 28, a tour of Beauport will be followed by “Codman, Sleeper, and the Gay Man Cave,” alecture at the nearby Rocky Neck Cultural Center by Wheaton College art-history professor Tripp Evans. He plans to discuss “how these men disarmed the stigma of same-sex attraction by creating spaces that asserted their authority, provided sanctuary, and reimagined the historical past.” (Ogden Codman Jr., himself an interior designer, and co-author, with Edith Wharton, of The Decoration of Houses, contributed to alterations of the decorative scheme of the Codman Estate, in Lincoln, Massachusetts, now also owned by Historic New England.)

Other special tours offered throughout the 2018 season include “Nooks and Crannies” (the first of them on May 26 and June 16), which take visitors on a longer, more detailed tour of rooms not seen on the regular tour, and “Designing Beauport, Room by Room” (beginning on June 8), which delves into Sleeper’s personal process and progression in creating the mansion. “Touring the house, you can begin to see the early rooms with an English theme and then see the additions, in 1910 and 1912, and the emphasis on Americana—the Pine Kitchen, the Franklin Game Room—and see how he moved through different phases, and when he gave up wallpaper,” Van Koevering explains. “He clearly loved glass, and displaying it, but he didn’t start collecting it until 1917. The amber-glass window in the central hall was the last reconfiguration of the house, in around 1929.”

Beyond Beauport, friends in Eastern Point and Boston sought Sleeper’s artistic talents. After the war, he chose to work as a professional designer, opening an office in Boston (where he lived when he was not in Gloucester). His clients included Isabella Stewart Gardner and Henry Francis du Pont, for whom he worked on a Long Island estate and, in the latter 1920s, as a consultant on a remodeling at Winterthur, the Delaware estate that is now a premier museum of American decorative arts. In the early 1930s, Sleeper also traveled to Hollywood to work for several celebrities, and he was working on a Vanderbilt family home in Connecticut when his life was cut short by leukemia. He was buried in the family plot at Mount Auburn Cemetery, and Andrew wrote a Gloucester Times tribute to his friend, noting, among other assets, his “impeccable taste” and “ingenuity in color and design which was distinctly creative.” (Andrew died two years later of influenza; his ashes, at his request, were scattered from an airplane flying over Eastern Point.)

Beauport drew crowds even during Sleeper’s lifetime; it was not that unusual for people to show up at the front door requesting a tour, which Sleeper’s longtime housekeeper, Mary Landergan Wonson (who stayed on after his death), typically obliged. He had earned a national reputation as a designer, curating decorative art exhibits and serving as a consultant to museums and collectors. In 1924, those planning the new American wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City spent several weeks at Beauport, soaking up the placement of antiques and color schemes of its period-style rooms. From 1909 to 1911, Sleeper even served as the first “director of museum” (overseeing the collections) at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, which later became Historic New England.

Sleeper’s brother inherited Beauport, but couldn’t afford to keep it. In 1935, the conservation-minded Helena Woolworth McCann, heir to the Woolworth department store chain, bought the mansion and preserved it virtually as Sleeper had left it. The McCann family spent several years summering there, but by 1941 both she and her husband had died. Their children, knowing their mother’s wish that Beauport be preserved as a house museum, donated it to Historic New England with the caveat that they could stay there whenever they wanted. One of them often did, into the 1970s, amicably closing the door to her quarters in the “Red Indian” room when tours came through.

And therein lies much of Beauport’s appeal. It’s not stuffy, or built on a grand scale; and it lacks the ostentatious flash of many of the Newport mansions. Instead, the place speaks to a generous creative spirit, and still holds a warmth that’s unusual in a house museum. “It was a place that was lived in, was comfortable, and enjoyed,” Van Koevering says. And it will just stay that way.