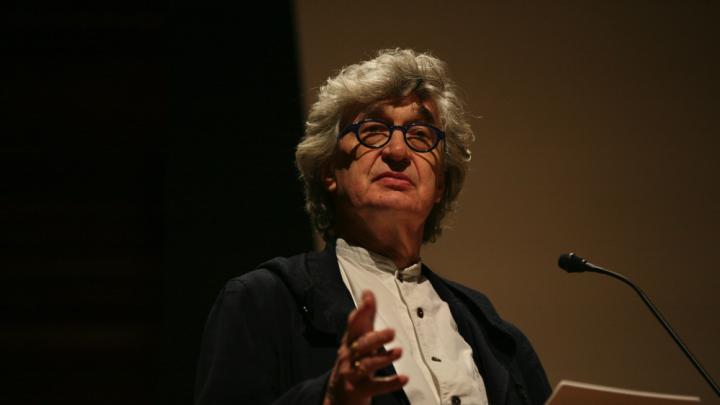

Every time he cued up a clip, and the lights dimmed in Sanders Theatre, the director Wim Wenders would step back behind the screen. Hands in pockets, head bowed, he’d take a little walk in the dark, and then wander back to the podium to continue speaking. Wenders’ talks on April 2 and 9, the final installment in the 2018 Norton Lectures on Cinema, were centrally concerned with space and how it’s traversed. Journeys have been a defining theme of his career. Associated with the New German Cinema movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Wenders channeled his generation’s thirst for freedom into rambling, drifting road movies.

His first lecture at Harvard, “The Visible and the Invisible,” discussed cinema through a series of dualities: the seen and unseen; respect and disrespect; attraction and repulsion. As a young filmmaker, said Wenders, “I was convinced that films were strictly the realm of the visible. Of course, I was a very good socialist. After all, it was 1968. And so my creed was that films dealt with the material world, period.” He played two sequences from his early feature, The Goalie’s Fear at the Penalty Kick: one in which the main character, Bloch, pokes through the apartment of an old flame, and another that captures an apple hanging in a tree. Though his editor complained that the latter shot had no meaning, Wenders argued, “It’s a real thing. It’s just there, without a purpose. That’s enough for me.” Like the soccer player, at the time he was interested only in people and in things. “No metaphysics loomed behind the surface. There was no behind.”

Fifteen years later, Wenders’ outlook changed, and his movie Wings of Desire followed the flight paths of unseen angels in Berlin. One, Damiel, falls in love with a trapeze artist, and in the clip Wenders played, follows her to her trailer, touching her personal objects and then, very gently, her shoulders. By then, he explained, he’d learned that movies can also access the invisible.

“What is it that you remember of the movies you've seen? Think of your favorite film. What has remained? What is it that you treasure? Picture it,” he later instructed. “I’m sure you cannot see it in front of your eye, so to speak, shot by shot with dialogue, music, sound framing camera moves—no. Then your brains would be data storage units.” Rather, Wenders said, people remember what these films evoked, or provoked, in them. He learned this lesson most acutely during a painful period in his life when his production company went bankrupt, and the rights to his films went into private ownership. The works seemed orphaned, he said, until he realized that they ultimately belonged to the audience who loved them. Movies only lived as long as they were watched, and remembered. Eventually he bought back the movies through a nonprofit foundation, and began restoring them digitally so that they’d be accessible to the public.

He illustrated this point with a clip one of his favorite films, Francois Truffaut’s 1966 adaptation of Fahrenheit 451. Montag, a former Fireman, seeks refuge in a colony of literature-lovers. There, each inhabitant memorizes a different work, word by word, so that they can be passed down forever. When works belong to the public, and live on in the imaginations of the viewers, said Wenders, “This is the last kingdom of appropriation.”

One last duality: a generous work opens “ample space” for the audience to read between the lines, or the frames; a “stingy” work leaves little. Wenders concluded his lecture using another’s voice, a clip of Leonard Cohen singing “Anthem”: “Forget your perfect offering/There is a crack in everything/That’s how the light gets in.”

Wenders also opened his second lecture by digging down into its title, “Poetry in Motion”—a topic that “seemed right down my alley, something to think about together with you.

“I like reading poetry,” Wenders continued. “Not too much, though—not many poems in a row. Just one or two a day. At night. It changes your entire rhythm. It alters your view. You enter into a different realm of peace, like into a different time zone of thought.” He then invited the audience to think about what elevated some motion pictures into poetry, to seem to embody poetry, and what made certain images poetic. Art films he declared “quite pretentious,” and commercial, story-driven films owed too much to the worlds of prose and theater.

His lecture presented three examples. First, Wenders offered a close read of Yasujiro Ozu’s last black-and-white film, Tokyo Twilight (1957),* about two sisters and their absent mother. Ozu was a master of making portraits of everyday life that felt spare, modest, and free, according to Wenders: “I consider them utterly poetic.” For the lecture, he layered together sequences showing the family members as they enter the house through a sliding door—first announced by its ringing bell, then glimpsed through a cut-out window. This visual motif creates structure the way rhymes might for a poem, suggested Wenders, and its repetition and slight variations accrete meaning poetically.

After these images of homecoming, Wenders then discussed scenes of outward motion, namely from his road movies. Though in one of them, The State of Things (1982), a character argues that “You can't build a movie without story. Ever build a house without walls?” Wenders has often taken a more elliptical approach to narrative. In Kings of the Road (1976), for example, he didn’t start out with a scripted story, but an itinerary. The cast and crew wandered from setting to setting, throwing the characters into situations and observing their interactions. “This free-wheeling approach to allow so much reality to enter your fiction that you end up receiving one gift after another,” said Wenders. “That might be another definition of poetry: allowing gifts to happen.”

The lecture’s last and most literal case study was his documentary, Pina (2011; filmed in 3D, but projected in only two dimensions on Monday). Initially planned as a collaboration with the choreographer Pina Bausch, upon her death the project transformed into a tribute in dance, with members of her company performing her work and sharing their memories of her. “I have nothing to add to this,” Wenders said, when the lights came back on. “Poetry in motion was happening in front of my camera.”

During the Q&A session, Wenders paired these reflections on the past with a pitch for his new work—a documentary about Pope Francis. “He’s a very poetic character so to speak, insofar as he is a very free man,” said the director. “I was amazed to get to know him so well, to realize how courageous he was, how much he was able to leave the framework he was given—but the film is not out. So you can go see it in a month, hopefully.”