HARVARD GRADUATE STUDENTS have voted 1,931-1,523 to form a labor union, per a count taken at the regional National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) in Boston today.

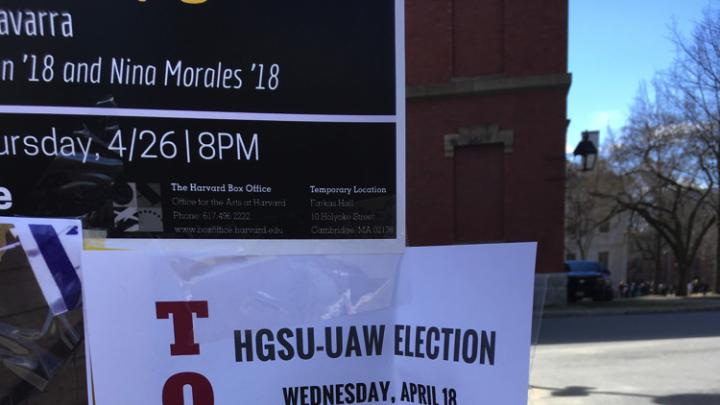

The outcome means that thousands of Harvard graduate and undergraduate students engaged in teaching and research can begin collective bargaining with the University through the Harvard Graduate Students Union-United Auto Workers (HGSU-UAW), unless Harvard challenges the results of the election. The election took place April 18 and 19 at polling places in Cambridge, Longwood, and Allston, covering an electorate of more than 4,500 graduate students in teaching and research positions and 300 undergraduates in teaching positions. Representatives from Harvard, HGSU-UAW, and the NLRB gathered to count the ballots nearly all day Friday. A total of 146 students voted under challenge (meaning they weren’t on the list of eligible voters), which was not enough to affect the outcome of the election.

Harvard did not immediately say whether it would begin bargaining with the union. The University has a week to file objections to the election, and challenges to student unionization at other universities pending before the NLRB could revoke graduate students’ collective bargaining rights, “Harvard appreciates student engagement on this important issue,” University spokesman Anna Cowenhoven said in a statement following the vote count. “Regardless of the outcome, this election underscores the importance of the University’s commitment to continuing to improve the experience of our students. We want every student to thrive here and to benefit from Harvard’s extraordinary academic opportunities.”

“We’re really excited—I think all our hard work has shown all along that we were going to win here, and we’re glad to be validated by the high turnout and votes from students,” said Abraham Waldman, a Ph.D. candidate in chemistry and chemical biology. Niharika Singh, a Ph.D. candidate in public policy, added, “We're really excited that Harvard has agreed to bargain, and we’re excited about all the issues we've been talking about to make our school better. We're so pumped—so much work from so many amazing people, for so many years. It feels great.” Union organizers regard Harvard’s agreement to hold the election as an agreement to bargain.

“We're excited for what this means for grad students around the country,” said Gabriel Schwartz, a Ph.D. candidate in population health sciences. “We just showed the world that if we can beat the wealthiest university in the history of the world, so can you.”

The election was Harvard’s second: graduate students previously voted on unionizing in November 2016, an election that turned out to be inconclusive. An initial vote count showed that 1,456 students voted against unionizing and 1,272 in favor, but a significant number of ballots cast were under challenge. After more than a year of legal battles that reached the federal NLRB in Washington, Harvard was ordered to hold a second election when the NLRB ruled that the University had failed to provide a complete list of eligible voters prior to the election, creating confusion about eligibility.

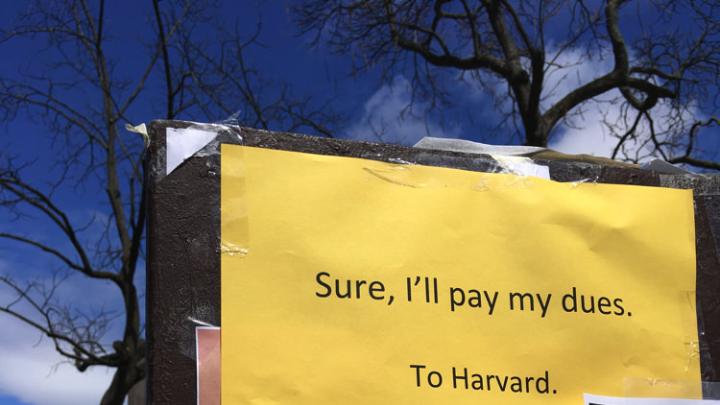

Harvard graduate students have been organizing to form a labor union for more than three years, citing many conditions that they hoped to improve through collective bargaining with the University—among them salary levels, access to dental insurance and dependent health insurance, and consistency in pay for teaching course sections. Many students pointed out that the University guarantees health insurance for only five years, even though doctoral candidates in many departments (particularly in the humanities) take longer to complete their degrees.

In August 2016, the NLRB ruled that graduate students at private universities should be considered employees with the right to form unions. Harvard has argued at every stage of the process that graduate students have an academic, not a managerial, relationship with their faculty advisers and with the University. “Both collective bargaining and arbitration are, by their very nature, adversarial,” the University argued in a February 2016 amicus brief in the same case. “They clearly have the potential to transform the collaborative model of graduate education to one of conflict and tension.” In an email sent to the Harvard community this month, provost Alan Garber wrote that a union would also prevent individual students from negotiating their working conditions directly with the University: “A majority ‘yes’ vote means that the HGSU-UAW would be the sole channel through which students in covered positions could have a say on wages, benefits, appointments, work hours, and work conditions. The HGSU-UAW would negotiate with the University’s Office of Labor and Employee Relations on behalf of thousands of students in more than 60 distinct academic programs to try to reach a contract in the same way that other unions on campus negotiate.”

Harvard’s is one of the most high-profile graduate-student union elections taking place on the national stage. Graduate students at Columbia, 72 percent of whom voted to unionize in December 2016, recently voted to strike after the administration announced that, rather than bargain with them, it would seek judicial review of the NLRB’s position on graduate students’ bargaining rights. That process would have implications for student-unionization rights nationwide. Columbia had already appealed its graduate-student union election unsuccessfully multiple times through the NLRB.

The Second Vote in Context

HGSU-UAW was notably better organized in the weeks leading up to this election than the previous one: student organizers at the Law School and other professional schools, not just Ph.D. candidates, rallied support among their peers, and the union’s social-media messaging stressed the benefits of unionizing for students across Harvard. Two students argued in a Harvard Law Record op-ed earlier this week that a union could help professional-school students make gains on issues of tuition and student debt. Those efforts were probably important to the ultimate outcome, given the unusual composition of the electorate. The NLRB’s August 2016 decision that graduate students are entitled to collective bargaining rights was surprisingly broad: it included in its ruling any students who are engaged in teaching or research work. Students organizing with HGSU-UAW could have formed a bargaining unit that included only doctoral students, but chose instead the broadest group that could be covered by the NLRB’s ruling, including doctoral students, law students, master’s candidates at the professional schools, and undergraduates. That choice posed significant challenges to organizing, bringing together students with vastly different career aims, and creating doubts about whether a single union could adequately represent all their needs.

Now, HGSU-UAW will be challenged with unifying the students they represent—not an easy task, if the fierce unionization debate on campus is any indicator. The campus discussion has often gotten away from the facts, focusing on students’ visceral fears rather than weighing their needs and interests. During the graduate-student-union debate hosted by The Harvard Crimson in March, for example, union opponents frequently discussed the worry that a strike would interfere with the work of science students, who need to be able to go to lab to do their work. But a strike is a last resort in a negotiation process after other mechanisms have been exhausted, and would require an affirmative vote from two-thirds of the union’s members—meaning it would be nearly impossible to authorize a strike without buy-in from science departments.

A footnote to the December 2017 decision by the federal NLRB, in which Harvard was ordered to hold a second election, noted that Harvard’s narrow appeal did not challenge the employee status of graduates students, and thus their right to unionize. William J. Emanuel, a Trump administration appointee to the NLRB, believes that matter “warrants reconsideration.” Such a move wouldn’t be unprecedented—the NLRB has already reversed its position on the union rights of graduate students twice since 2000, with changes in presidential administrations. Many private universities faced with unionization campaigns across the country appear to be counting on it to do just that.