Many who work in and around the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts have a weird relationship with the French modernist architect who designed it. Le Corbusier is a mythic figure for Harvard’s art students: his notoriety, when combined with the loudness of his architecture, means that making art able to hold its own in the building feels like shouting over a lawnmower.

Artist, filmmaker, and MIT professor Renée Green has been making work at the Carpenter Center during a two-year residency—enough time to get to know the space intimately. She has set up colorful modular viewing stations for displaying videos, installed grids of images of California infrastructure, and presented essay films, ephemera, sound works, and print publications. Throughout, “I’ve used spaces that I wouldn’t ordinarily imagine would be used,” she says, “more interstitial spaces”—under the stairs in the basement, in the vertical vitrines, in a corner of what is now the bookstore at the top of the building’s ramp. She’s excited about her final exhibition, “Within Living Memory”(on view through April): she gets the whole place to herself. The culmination of her residency, it contains works made in the past decade and spanning many media. Gravitating around themes of habitation and displacement, the show highlights projects reflecting her attention to modernist architecture.

Renée Green

Photograph courtesy of the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts/Harvard University/Renée Green

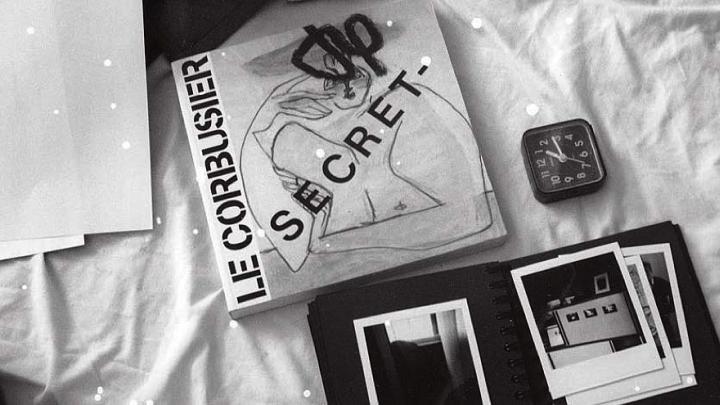

Before her time at Harvard, Green’s last encounter with Le Corbusier was in 1993, when she ventured to Firminy, France, to live in a half-deserted housing unit that had been part of his multi-site modernist residential concept, Unité d’habitation. She reflects on that (literal) residency in Secret, a rarely shown trio of videos on view in “Within Living Memory”; her new moving-image work, Americas : Veritas, premiering during the exhibition, considers the Carpenter Center alongside his only other built structure in the Western hemisphere: Casa Curutchet, in La Plata, Argentina—5,404 miles away. The pairing feels, in her words, “oddly peripheral” in contrast with Le Corbusier’s imaginings. Green is fascinated by the wide gap between his dreams for the Americas—re-doing entire cities—and what he actually managed to build.

Green has a long-term interest in modernist architecture: her essay film Begin Again, Begin Again, also on view in the exhibit, is an attempt, in her words, to “think with” the eponymous West Hollywood house built by the Austrian-American architect R.M. Schindler in 1922. Designed to facilitate an experimental and communal lifestyle, the building gave rise to the California strain of modernist architecture. The film begins with a deep rumble of a voice announcing, “Begin again. Begin again. Begin again,”where every “again” is a little more electric and each beginning has a little more weight. Teal seawater tumbles over the camera. The voice tallies every year from Schindler’s birth in 1887 until the film’s own making in 2015; shots of the house and surrounding nature are punctuated by archival footage of twentieth-century commercial and military activity. Green makes the past feel strangely close. How, the film asks, are Schindler’s words and buildings differently experienced 60 years after his death? How can time dilate lives?

Another recent work continues this line of inquiry into how ideas, people, and built structures move across time and space. Green’s 2017 essay film, ED/HF, engages with the life of German filmmaker Harun Farocki, whose work explicitly reflected on the medium’s political potency. The script of ED/HF is a collage of both Farocki’s and Green’s writings on lived space, migration, and the creative process, interspersed with quotations from poets Rainer Maria Rilke and Paul Celan, among others. But all this is voiced by a single narrator: hearing the uncited audio, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to tell where Farocki ends and Green begins. They share a single set of vocal cords. Green, who calls the piece “a film as a conversation,” says, “I wanted it to be blurry.”

She and Farocki exhibited together until his unexpected death in 2014. He wanted to be a writer, and so she sought out his personal writings as source material for the script. “When a person is dead you can imagine what you like,” says the narrator of ED/HF. “You can also review what they left, if you can find it.” The process of writing the script seems like a kind of verbal knitting: she wove his voice into her own.

“Both ED/HF and Begin Again, Begin Again are about considering a lifespan,” she says. Modernist buildings like the Carpenter Center, she notes, were not built to last longer than 100 years—not that much longer than a human life. She’s fascinated with what will happen if they last longer.

Green’s creations are sensitive not only to longevity, but also to how quickly “right now” becomes “just a moment ago.” Her work articulates a desire to be attentive to the passage of time. She’s titled her residency “Pacing,” suggesting how the work of these two years has been cumulative. Each project overlaps its predecessor, and all of them address the Carpenter Center: “I can do [the work of the residency] over time in different ways, minimal, maximal, whatever, in between.”

As for the shadow of Le Corbusier himself, Green is unfazed. She’s very aware of his glossy notoriety: “He was very engaged with creating his archive, and having some kind of trace of everything he ever did,” she says. At the same time, she adds, he had failures and false starts and a list of projects he didn’t get to. She’s interested in the architect—as with Farocki and Schindler—as a human being.