Nell Scovell ’82 went wherever they’d let her be funny. Her early writing career can be seen as a progression of bigger, freer venues where the bosses would let her crack wise: first the sports sections of The Harvard Crimson and The Boston Globe, then the glossier pages of Spy and Vanity Fair. At the latter, a colleague gently suggested, “Nell, I don’t mean this as an insult, but I think you could write for TV.” And so she found the medium where she could really act on her comedy compulsion.

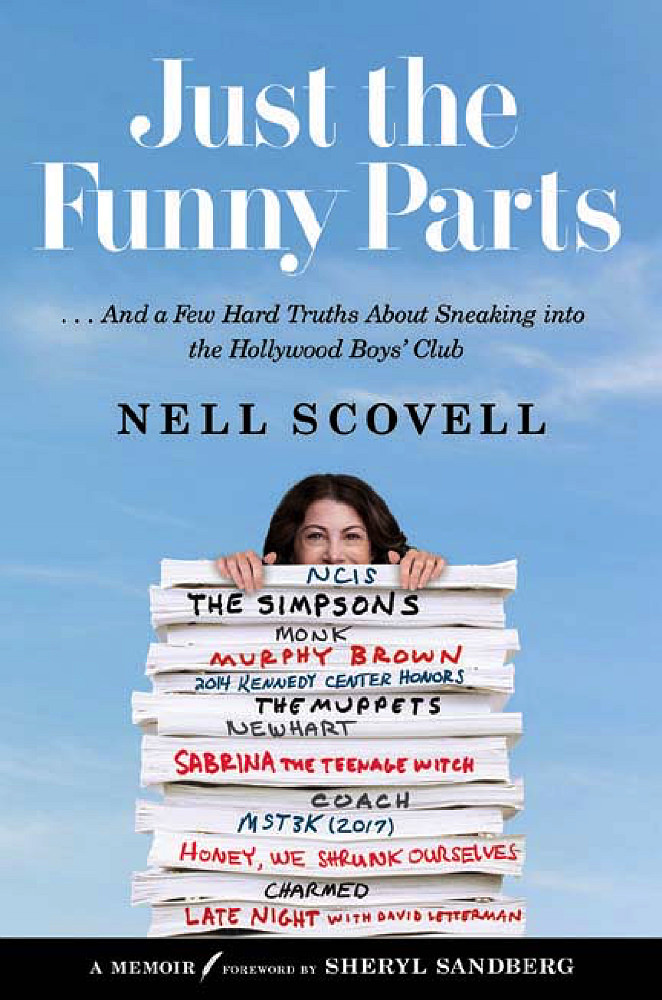

But when Scovell set about drafting her memoir, Just The Funny Parts, she was nagged by a different need—the sense that, as she puts it, “If I don’t say something, no one will know I was there.” There meaning the staffs of the Smothers Brothers, Bob Newhart, and David Letterman shows, or awards ceremonies and the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, or just showbiz itself. “I want my kids to know,” she adds.

She had lots of primary source material. From the start, some version of that impulse—“I want my kids to know”—made her keep everything: correspondence, silly doodles by friends, early scripts with scribbled notes (“wordy”; “too jokey”; “ALL BETTER”). “I always thought TV would go away,” Scovell says. “I just kind of thought that this is something I’m going to show someone: ‘See? For a year, I was a TV writer!’”

In 30 years and counting, she has written comedy and drama, mystery and sci-fi, and even a Lifetime movie about a college reunion that ends with blackmail (co-scripted with her sister, Claire Scovell Lazebnik ’85; Scovell also directed). She’s gotten to make a mark on beloved fictional figures: thanks to her, Homer Simpson tried fugu and Miss Piggy flashed her tail on the red carpet. (Scovell likes to say, though, that Sheryl Sandberg ’91, M.B.A. ’95, with whom she co-wrote Lean In, is her favorite character to write for “other than Murphy Brown.”) While on the staffs of long-running workhorses like Charmed and NCIS, and as the creator of the sitcom Sabrina the Teenage Witch, she mastered a specific craft: overstuffed, comfy plots that are as easy to sink into as a favorite armchair. Across an unusually broad range of genres, her writing has been driven by a goofy, antic imagination. The John Doe turns out to have three fiancées. A demon shrinks the heroines down to five inches. A teenager’s first spell turns everything into a pineapple.

Scovell says that she feels a kind of survivor’s guilt about this success. “It’s not that I was the funniest female writer ever, but I managed to find a path. I was a good ‘culture fit’ in certain ways.” Her Harvard cred gave her an in, and thanks to her sports-desk days, she was unfazed by being the only woman in a room, or by shouting men in general. Whether with a bemused smile or through gritted teeth, she could deflect comments like, “Since when do we have pretty little girls working on this show?”

So her book is studded with pointers. Take any job that comes your way. Don’t mistake sexual power for real power. Sometimes sincere trumps snarky. (In an interview, she offers a few more, on the spot. “Comedy is always easier when we’re with familiar characters”—so, in a first episode, “Every line not only has to move the plot forward, it also has to illuminate the character.”) There’s also something to be learned from the one-liners embedded throughout her narrative like razor apples. If a new colleague asked if she had kids, she’d blithely reply, “I’ve got two sons, but I’m blanking on their names right now.” Recalling a misogynistic former boss, she writes that they never met again, then tosses off, “It’s unlikely we will since I don’t get to Branson, Missouri, much.” It’s these moments that really show how Scovell made it in entertainment: thick skin, secret steel, and the ability to parry.

Yet hers is not a straightforward growth narrative. Instead, it zigzags from triumph to disappointment. A “Job Timeline” lists every single project she ever worked on, including the unshot and unaired, each rewrite and every rejection. Then there are the lists of jokes that didn’t make it, a chapter all about shows that she narrowly missed working on—it’s like a movie made of outtakes, as if she stitched a narrative from what she’s swept up from the cutting-room floor. “I have cried in every parking structure in Hollywood,” Scovell confides.

In the book, she quips that the flipside to that William Goldman chestnut, “Nobody knows anything,” is the helplessly hoping, “You never know…” Even to her, Hollywood remains baffling, a system operating on variable rewards. Hopefuls are lured in by intermittent reinforcement, like gamblers playing the slots, or caged rats. “Pressing the lever may lead to insanity,” she writes, “but how else are you gonna get a pellet?”

Scovell admits that she sometimes chafes against the suggestion that she must give herself over to mentoring young women. After all, she still has aspirations of her own. She’s working on a pilot about a divorced one-percenter who moves in with her school-teacher sister and her school-nurse brother-in-law. She might like to run a show again. She would love to direct another movie. “I’m not done. And I don’t want to admit that it’s over just yet. I want one more shot!”