“Gorey’s Worlds,” at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, explores what inspired Edward Gorey ’50, mostly through works he bequeathed to the Hartford museum. They range from nineteenth-century folk art to photographs and drawings by Eugène Atget and Edvard Munch and an oil painting, Dandelions in a Blue Tin (1982), by the brilliant and reclusive landscape artist Albert York. Gorey was “ahead of his time” in appreciating York’s work, and acquired eight of them in the 1980s, says Erin Monroe, Wadsworth’s associate curator of American painting and sculpture. She believes Gorey was drawn to something “subtly subversive” in York’s “ordinary” subjects, and to the humor in the carefully arranged weeds.

Images of skeletons, alleyways, animals, skylines, dancing figures, and gravestones also appear in the show, as they do, one way or another, in Gorey’s own legendarily macabre and dry-witted works. Dozens of borrowed objects—his own art, fur coats, and handsome jewelry, along with 1970s portraits by culture photographer Harry Benson—flesh out a singular creative spirit.

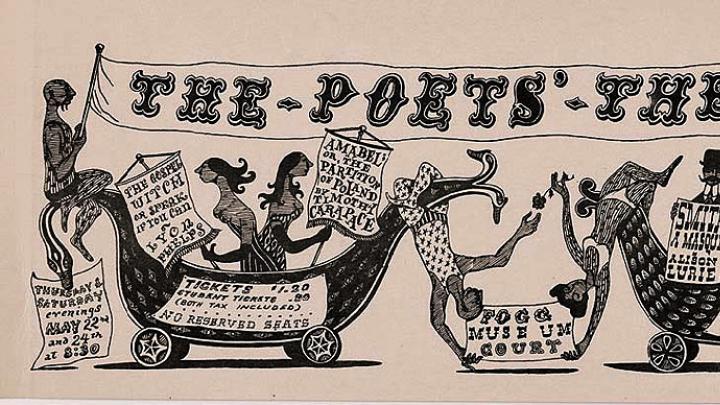

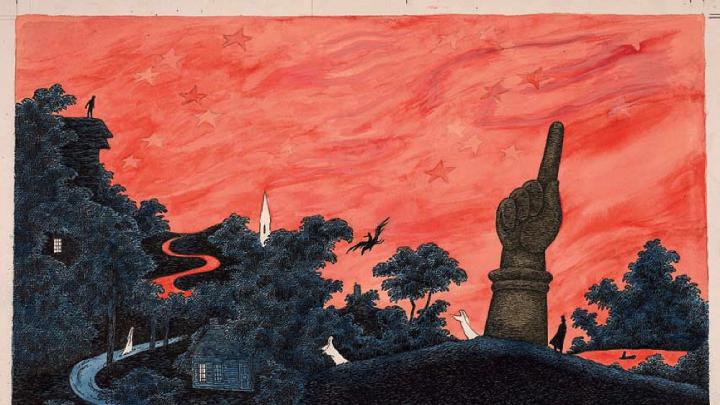

Gorey died in 2000, leaving no explanations of his attachment to the bequeathed items. But Monroe’s research suggests connections: parallels between Church and Graveyard (c. 1850), a folk-art sketch by an unknown artist, and Gorey’s Haunted America, a 1990 watercolored pen-and-ink design for a book on supernatural short stories; or between many Gorey-esque objects and those in Atget’s Naturaliste, rue de l’Êcole de Médecine (1926-27; printed by Berenice Abbott). On view, too, is a print of a 1952 illustration Gorey made for the Poets’ Theatre, a Cambridge group that included Frank O’Hara ’50 (Gorey’s College roommate), and of which Gorey was the resident artist. “It was about as counterculture as you could get in the early 1950s,” says Monroe.

The flyer reflects the link “between text and image, and a unique typography and theatricality, that are the foundation” of his artistic career, she notes. Acrobats, gloved women in gowns, and mustached gentlemen are depicted as “languid bodies, graceful, and unusually boneless,” resembling his later drawings. His own “presentation—fur coats, high-top sneakers—which seems sort of pre-hipster now, was strange on campus then, and even when he moved to New York City,” she adds. “At six-foot-four, he didn’t necessarily blend in. I think he was OK with everything that was strange and unexpected.”