Entering Inventur: Art in Germany, 1943-1955, visitors first face a small, drab painting hanging alone on the wall. It depicts a Cubist heap of white doorways, gaping like a chorus of ghostly mouths, the lintels heaped like bones. Fallen Façades (Berlin Ruins) is uncharacteristic of its maker, Jeanne Mammen, famous for glitzy portraits of 1920s nightlife. It’s emblematic, though, of the exhibition. Many artists who continued to work under the Nazi regime, and in varying states of secrecy, produced pieces that seemed out of stylistic step with the rest of their oeuvre. These artists had to be resourceful—here, Mammen repurposed a cardboard panel used to black-out a window during air raids. Moreover, Fallen Façades is a kind of revisionist work, covering up an earlier image whose rusty streaks are just discernible beneath layers of dark oils.

Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg, FrK 4237/1995. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo: Jürgen Diemer.

Inventur, opening at the Harvard Art Museums on February 9, excavates a period that’s been overlooked, and even obscured, in the history of German art: the end and aftermath of the Second World War. In the conventional narrative, postwar art begins afresh in the 1960s. Critics and scholars have declared the preceding years a “gap,” with many famous modern artists suppressed or exiled. “What we know, as Americans, is the exile story,” Lynette Roth, Daimler curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum and head of the division of modern and contemporary art, said on a recent tour—referring to figures like the Bauhaus émigrés and Max Beckmann. Inventur examines a different cohort. “These are artists,” she said, “who were able to, let’s say, fly under the radar.”

The exhibition, surveying some 48 artists from across the country, takes its name from a sonnet by the lyricist Günter Eich, in which a prisoner of war inventories his possessions—a nail, a shaving kit, a pair of socks in a bread bag. The poem is commonly taught to German schoolchildren as marking the start of German postwar literature. The year Eich composed it, 1945, has been called Stunde Null, or zero hour, sequestering the Nazi regime from Germany’s fresh beginning. “We now know, of course, that that is not possible,” said Roth. So Inventur’s accounting begins in 1943, when the defeat at Stalingrad and increased Allied air attacks augured German military collapse. The endpoint is 1955, in the midst of the country’s economic “miracle.” But Inventur does not mount a single, coherent counter-narrative of this period. Instead, in Roth’s words, it is structured around several “case studies,” revisiting a handful of key figures across the 12-year stretch.

Inventur moves chronologically. The first of its three galleries provides a snapshot of the different ways artists kept themselves busy, and alive, under the Nazi regime. Even without government approval to make and show pieces, and with resources dwindling, artists found ways to work. Some found means of creative expression under the guise of practical aims, as when Oskar Schlemmer made “splotchographies,” a series of panels demonstrating different lacquer effects, while he was employed at a factory. Others pursued small creative projects in secret: doctoring a copy of Hitler’s book with rude, surreal collages, Juro Kubicek made Mein K(r)ampf. (This was never intended for exhibition, said Roth, and the current owner of the text has an envelope full of clippings and photos that Kubicek never got around to pasting in.) Still other works, like Wilhelm Rudolph’s ink sketches of the ruins of Dresden, are seemingly straightforward documents of violence and destruction.

In the next room, it’s the late 1940s, and the war has ended. The walls display attempts to reclaim from Nazi ideology the possibilities inherent in humanity’s relationship to nature and technology. Sponsored by tech companies, figures like Otto Steinert explored what he called “subjective photography,” playing with unusual angles and prolonged or interrupted exposure times. Such ties between art and industry only strengthened over time, as artists embraced commercialism and poured their creative energies into furnishing and decorating domestic spaces.

The third gallery delves into the 1950s, its walls printed with a cheerfully mycelial pattern. Entering this space, Roth quoted the writer Günter Grass, who likened the art of this period to being “like so much wallpaper.” “And I thought, ‘Yes—yes, it is,’” said Roth, with a decisive nod. But, she argued, art came first, and industry followed. Overhead arched a long iron and aluminum lamp by sculptor Brigitte Matschinsky-Denninghoff, hanging still like a malevolent comet; below hung a printed plastic curtain that could be used as a room divider. Artists were understandably excited by the new abundance of such materials.

The final section of this gallery revises documenta, the landmark exhibition whose first iteration, in 1955, showcased German artists alongside their international contemporaries. Reintroducing the world to prewar modernists like Max Beckmann and Paul Klee, documenta, Roth explained, centered on abstract art. In this gallery, she took works that appeared in that show, like Karl Hartung’s green bronze sculpture Striding (Torso) and placed them alongside pieces by less fashionable, mostly forgotten, peers. In doing so, she aimed to return them to a German context, while simultaneously broadening viewers’ understanding of German art.

One of the exhibition’s central figures is the abstract painter Willi Baumeister, whose work can be traced from the industrial lacquer experiments in the first gallery to the porcelain vase and synthetic fabrics in the later ones. Another is Hans Uhlmann, who, while imprisoned in the 1930s for distributing communist leaflets, made sketches of fellow inmates while working in the prison’s print workshop. These became the basis for small sculpted heads he soldered in secret during the war, from steel and wire salvaged from bombed-out buildings. In 1955, documenta featured a steel arch he made; Inventur also displays a later, Calderesque, work, suspended from the ceiling.

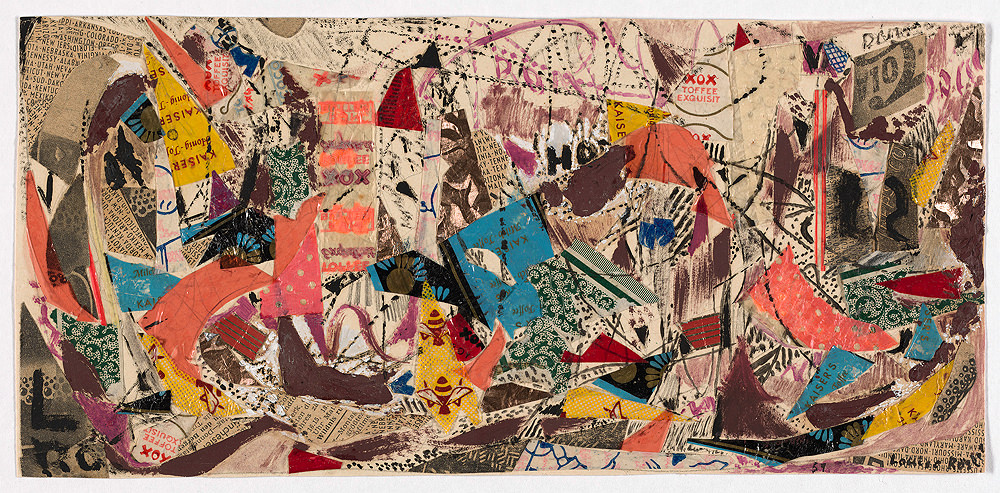

The new exhibition has also furnished an opportunity to bring out gems from the Busch-Reisinger Collection, including abstracts by the painter K.O. Götz. New acquisitions are highlighted as well, namely the colorful ruinscapes made by Louise Rösler as letterheads for correspondence with her husband, and her postwar collages repurposing candy wrappers dropped by American soldiers.

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Purchase through the generosity of Renke B. Thye, 2017.125. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Inventur tracks the work of those artists who stayed through and survived the war and its aftermath, spanning different generations, and different regions of the country—some of them far outside metropolitan centers. Drawing a jagged continuity between these years of art-making, the exhibition raises questions about complicity with totalitarianism. As the catalogue puts it: "By necessity, these are artists who were racially and politically accepted (or at least tolerated) by the Nazi regime." The sheer variety of work is surprising, absorbing, and troubling. Even their starkest images can feel, somehow, evasive. Some artists, like Otto Dix, sought to render their wartime experiences in universal terms—ruin, carnage, man’s cruelty to man—by deploying religious imagery; others, like Mammen, described themselves as being in a state of “inner emigration,” their art turning inward, and private.

“We want to look at this work and we want to see resistance. We want to see very clear-cut reactions to what just happened,” said Roth. Visitors should know: “You’re not going to find it.”

Inventur: Art in Germany, 1943-1955 will be on view through June 3, 2018.