This winter, an exhibit of contemporary paintings in the basement of Davis Square’s Somerville Theatre features animals. Medusa Fries Fish, by Florida artist Christine House, is clearly symbolic—but of what? A wild-haired lass in a slinky red dress stands with arms extended like pale noodles, bewitching (befriending?) a perky green fish, rendered in the Japanese Pokémon tradition, lying in a pan over roaring flames. Yet the improbable enchantress is herself transfixed by a mysterious squiggled spiral in the twilight sky.

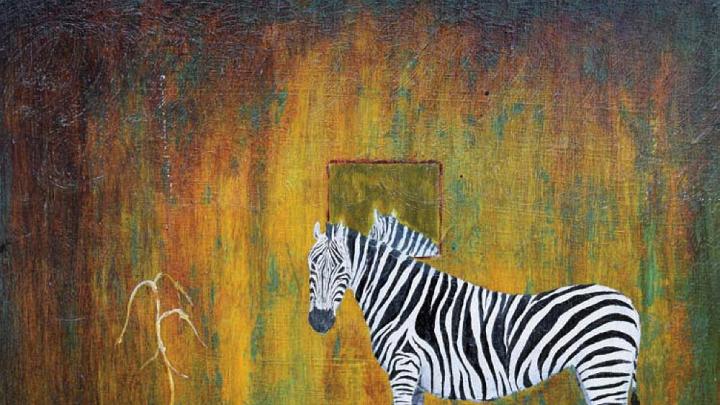

Woman Riding Crustacean

Image courtesy of the Musuem of Bad Art

Nearby is the evocative acrylic Woman Riding Crustacean. Here, an explanatory label suggests that the unknown artist might have been inspired by actress Debra Winger holding her own on “a mechanical bull in the 1980 film Urban Cowboy,” even as the figure “appears to be a blow-up doll mounted atop a giant lobster” or “a study for a larger, hopefully more erotically realized, work.”

On display through February 25, “MOBA Zoo” is the latest show culled from more than 700 works held by the Museum of Bad Art (MOBA). “We collect compelling pieces in which something has gone wrong in the execution or the concept,” said MOBA’s curator-in-chief Michael Frank. Typically, the works reflect either poor technique, or expertise painstakingly applied to produce hilariously overwrought results, or images that simply elicit a loud “Wow, what is that?”

“It’s not kitsch,” he emphasized. “But what is tongue-and-cheek…is that we’re not mocking the artists, we’re mocking the knitted eyebrows of the world of art criticism.” In essence, MOBA legitimately questions what, or who, makes a piece of art “important”—the idea that the “right person” has to say, “This is good”—and it has a lot of fun in the process.

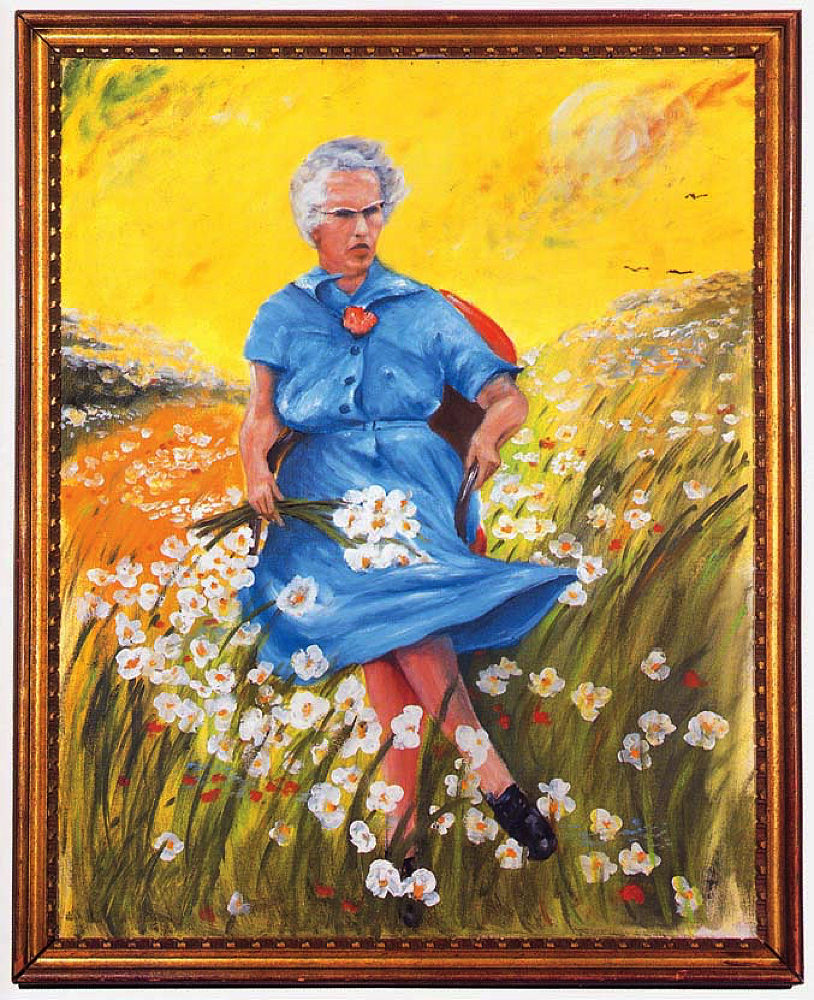

The masterwork that inspired it all, Lucy in the Field with Flowers

Image courtesy of the Museum of Bad Art

It all began in 1994 with Lucy in the Field with Flowers. Boston arts and antique dealer Scott Wilson acquired the portrait of a handsome grandmother, pensively poised under an aggressively yellow sky in a windswept meadow, from a Boston trash heap. He’d wanted to sell its frame, but upon seeing the painting, his pal Jerry Reilly objected, using a phrase that would be repeated with gusto through the years to come by those inducted into MOBA’s guiding renegade spirit: “You can’t do that! That’s so bad, it’s good.” Reilly took the tribute to someone else’s elder and hung it in his own West Roxbury home, said his sister, Louise Sacco, MOBA’s current “permanent acting interim executive director,” during a tour of the gallery.

Word spread of Reilly’s masterpiece, and others like it that he and Wilson and a few similarly inspired colleagues were soon scooping up from yard sales, thrift shops, and town dumps. But it wasn’t until “a busload of seniors from Rhode Island pulled up on his little residential street and got out to come see these,” Sacco said, “that we realized we had to do something bigger.”

Eventually they opened MOBA’s more or less permanent gallery in the Somerville Theatre, itself an historic, and beloved, place; satellite exhibit sites now exist in Brookline and South Weymouth. All the locales are donated space, there’s no paid MOBA staff, and admission is free. Donations and proceeds from the sale of postcards and a catalog pay for a telephone line, website, and storage of any art that can’t fit into Frank’s house.

People from all over the world submit photos of potential works, and sometimes just mail the works themselves to MOBA, Frank said, mostly because they’ve seen its Facebook page (which has 53,000 followers) or appreciate Frank’s 28 MOBA You Tube curatorial talks (of varying educational and entertainment value).

Frank is picky. He accepts less than 25 percent of what’s offered by others, and acquires most of the pieces himself through the region’s thrift shops and other affordable venues. Garbage piles in May and June, when local college students are preparing to leave town, have yielded some real treasures. He also scouts around when traveling for his paid occupation, as a gig guitarist and as family entertainer Mike the Hatman. “I’ve been to Cuba a lot, and there’s a strong strain of surreal imagery there,” he said in a phone interview from his Boston living room. “So I recently picked up a piece, that I’m looking at here now, that’s pretty damn bizarre.” He guesses it’s some sort of Welsh corgi, with no legs to speak of, in a rural landscape.

A backlog of artwork awaits cataloguing and what can be his lengthy interpretation process. That might involve Google name searches for any signed pieces (although most MOBA works are by unknown artists), as well as research to contextualize a given painting by identifying other art or events that might have inspired the work. Thus Mini-Marilyn En Pointe, in a show entitled “Dopple-hangers” at the Weymouth gallery, is a depiction of the American actress and sex symbol. But what may initially resemble pigs’ feet poking out from under her black dress are actually her own, attached to unseen knees bent as she’s jumping up, smiling at the viewer. Frank knows this because the painting is clearly based on an image he found online by French photographer Philippe Halsman, who, in the 1950s, captured a series of famous people in mid air.

Centaur and Biker (interpreted as “An obvious comparison of two bearded men and their personal horsepower”)

Image courtesy of the Museum of Bad Art

Over the years, MOBA has had shows in New York City, Santa Fe, and Minneapolis, as well as in Canada and Taiwan. “It was not my assumption that the irony of MOBA would translate” to Asia, Frank said, “but it seemed to be very successful, because the show was in Taipei and then moved to another city and was extended to six weeks.” He’s currently planning for a MOBA show in Tokyo next fall or winter.

MOBA’s art is primarily representational. With abstract works, Sacco said, it’s much harder to assess what artists intended to do, and if they succeeded: “To look at a Jackson Pollock—if that reputation wasn’t out there, if he wasn’t a well-acknowledged genius—the first time we saw his painting, we’d say, ‘Oh, someone spilled the paint—that’s what went wrong.’”

What’s often disconcerting in the MOBA collection is the steroidal level of symbolism. The exhibit “MOBA Zoo” features a 24-inch canvas titled Liberty and Justice that was donated in 2015. Frank’s label reads: “Reminiscent of Judith clutching the head of Holofernes, teary-eyed Lady Liberty celebrates her victory over the enemy and hopes peace can return to the city. In other news, her jaundiced bald eagle has caught a fish.” That sums it up, but omits the complexity of the background scenes of lower Manhattan with a military aircraft runway (from which planes and a helicopter are taking off), a ribbon of highway, and the Dali-style scales of justice dangling from the statue’s forearm. Frank resists discussing the work beyond the brief explanatory interpretation he’s attached to it. “To explain why it’s amusing or funny makes it stop being funny. I prefer to present the stuff and either you get it or you don’t.”

Sacco sees other themes within the MOBA collection. In landscapes, waterfalls mysteriously spring up, mountains arise from flat surfaces, and trees in a natural forest march along in straight lines. Goofy designs and strange objects, or blocks of color, crop up where artists seemingly “didn’t know what to do with all that empty space on the canvas,” she says. Then there are the creative contortions to avoid rendering notoriously difficult hands and feet.

In Safe at Home (which hangs in Somerville), players’ hands are either roundish blobs of paint or obscured by mitts, and the umpire’s protective vest is not on his chest, but slung over his entire left arm. There are other such juxtapositions. “Someone on the Red Sox is sliding into home from first base,” Sacco pointed out, “which is as puzzling as whatever the beast is that’s eating him.”

MOBA occasionally learns of an artwork’s provenance only after it has been displayed. The strange, dream-like watercolor He Was a Friend of Mine, featuring an angry cat and a benign-looking husky looming in clouds overhead, was painted by a homeless man and given to a benefactor who had provided him with food and art supplies, Sacco said. “And you know if the artist was here he’d be able to tell us exactly what he was doing, what this painting means to him.”

Years after MOBA salvaged the six-foot-square portrait Man in Puffy Disco Hat from a Back Bay loading dock (thanks to a call from UPS driver Bob Bean), it appeared in a newspaper article on the museum, and a woman called to say, “You’ve got a portrait of my husband.” “She came over here to see it,” said Sacco, “she and her twin sister, two little tiny ladies in their nineties, and told us that when her husband died, she had this painting made of him, from two photographs, in 1978. It had been hanging in her living room in the Back Bay and when she was downsizing she couldn’t keep it, so it went out into the trash. She was thrilled we had it—it was wonderful.” (The painting is on permanent display in Somerville because it is so heavy.)

The poignant exchange in Blue Face—Green Pepper defies explanation.

Image courtesy of the Museum of Bad Art

Sacco also reported that a surprising number of artists offer to donate their own works. If turned down by MOBA, she surmises, they may believe the piece is “not that bad.” If accepted, their creation has an audience.

Bone Juggling Dog Wearing a Hula Skirt, in “MOBA Zoo,” is among three works MOBA has accepted from Mari Newman, known in Minneapolis for her Outsider Art. The panel features a smiling ginger-bread-man-like dog, with brown fur overlaid with polka dots and with his tongue sticking out, against a background of dog bones, scores of white flowers, and swirling patterns of colors dabbed on in minute strokes. “The artist is legally blind,” Sacco explained, “so her works have a lot of detail because she can only see when she’s very close up to the canvas.” According to Sacco, Newman also has pieces in collections at the Columbus Museum of Art and the New Orleans Museum of Art.

MOBA’s works do share traits found in Outsider Art, Naïve Art, and even folk art, and sometimes it’s hard to tell what the differences really are. That begs other questions about its overlaps with fine-art criteria, Sacco said, “because we’re looking for something that engages, that gets you talking, that raises questions—you know, all of those are things that any museum will tell you they are doing.”

Malinkova, by Tatyana Lyarson (1998), was found by Frank in a Boston thrift shop in 2012, with the title (Russian for robin redbreast), artist’s name, and date on the back of the canvas. “The young woman’s head is slightly atilt under the weight of impossibly orange hair in this idyllic tableau,” he wrote in the accompanying label. “A tiny songbird has alighted from the dwarf tree bearing two green apples onto a one-dimensional chair, contemplating the coiffure as a potential new home.”

It’s a delightful image. Free-spirited, oddly Edwardian-looking: any number of people might like to hang it in their own home. “It really bothers me when people say things like, ‘That’s not bad, why is it here?’ ‘But, I like this!’” Frank said. “Yeah, I like it, too—that’s why I collect it. We like all these paintings. They are compelling, or we wouldn’t be doing this.”

He is also irked by nonchalant offers to buy MOBA’s art. “From time to time people say, ‘I need this and I will pay a lot of money,’” he said. “And invariably, they offer about $150, and I say no. We’re a museum, not a gallery,” he added. “They wouldn’t go to the MFA and say, ‘I really want that,’ and make a silly offer and expect to get anyplace. I mean, seriously, come on.”