For me, it’s not the commemorative McDonald’s commercials, nor the reverent social-media hashtags, nor simply the calendar that signals Black History Month: it’s February when the Sophia Stewart Matrix Hoax recirculates around the Web. The legend goes that Stewart, who’s black, pitched a short story to the Wachowskis back in 1986, which they plagiarized and turned into the Matrix franchise and, inexplicably, The Terminator saga. Supposedly Stewart sued them and Warner Bros. for copyright infringement and won a multibillion-dollar judgment. That this story has been debunked on Snopes.com and elsewhere does not keep it from finding an audience. Although the misinformation allegedly began in 2004, with an article published in a Salt Lake City student newspaper, the Stewart hoax persists more than a decade later because some of us want to believe it.

Kevin Young’s new book, Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News, is as exhaustive as its subtitle: part survey of modern imposture, part detective story about the origins of American fakery. Though he detours in Europe, profiling art forgers like Han Van Meegeren and a few other non-American figures, the focus is mostly on the history of artifice in this country. It’s an important book for 2017, not only because “fake news” is a part of the zeitgeist, but because public discourse about white supremacy and political hucksterism suffers from citizens’ short memory. With Bunk, Young ’92 brings this collective amnesia into relief. P.T. Barnum, JT LeRoy, Rachel Dolezal, Donald Trump, and many other figures are all subject to his analysis.

The revelation of this information is mixed with the disappointment of not having access to such a compendium before now. The natural thought is: we needed this book years ago, before the 2016 election. But as Bunk makes clear, trickery has been an inextricable part of American culture since the mid-nineteenth century, if not earlier—and moreover, it’s inextricable from the social construct of race. The very term bunkum comes from a Buncombe County, North Carolina, congressman’s filibuster on the Missouri Compromise. The confluence of artificial lingo, race, and politics, then and now, is enough to make one feel stuck in a time loop. The big American hoax, like The Terminator, seems to say, “I’ll be back.”

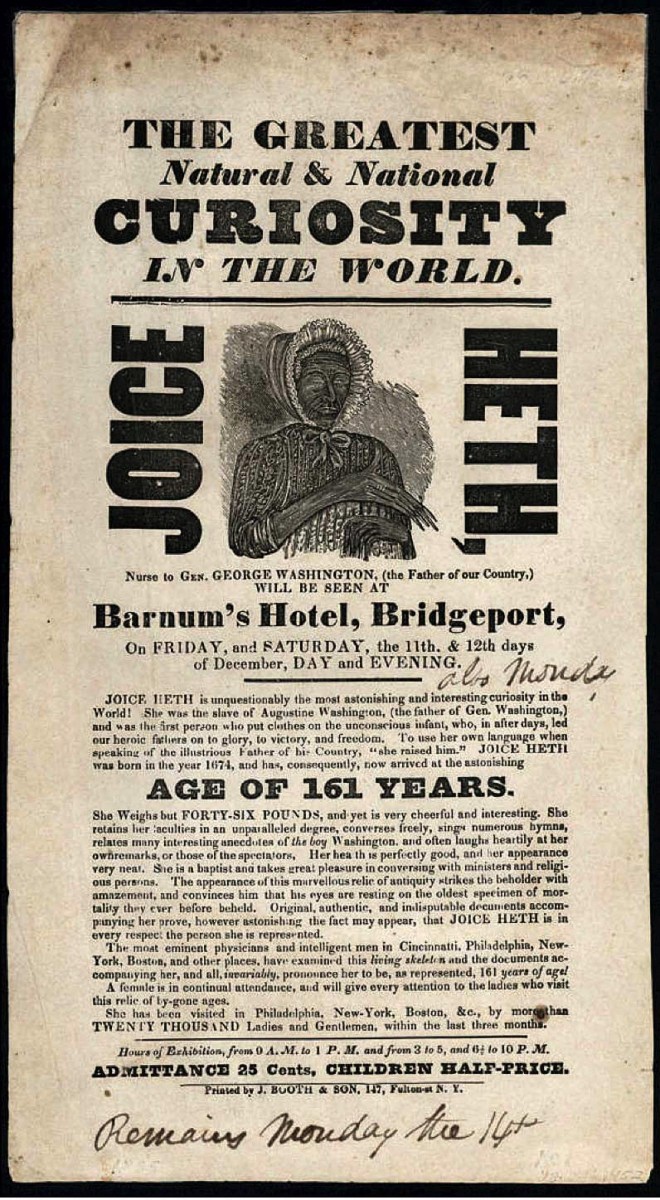

P.T. Barnum’s circus prominently featured “George Washington’s nurse,” in reality an enslaved woman named Joice Heth.

Image from Wikipedia

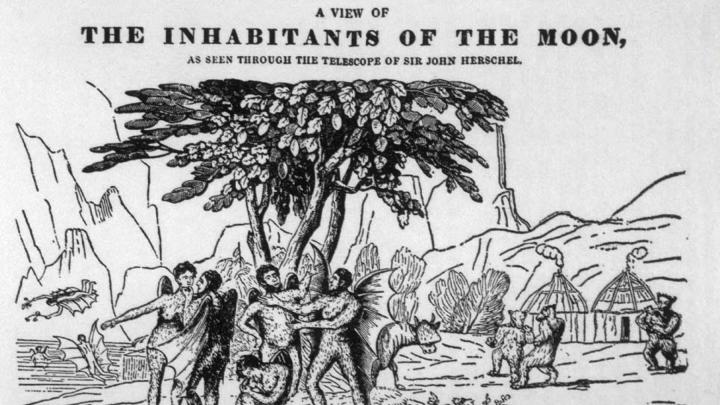

Bunk’s intricacy extends to its author’s method of organizing his subjects, which does not follow strict chronological order. He makes ties between seemingly disparate episodes, confidently suturing the U.S. cycling scandal to Edgar Allen Poe, and the writer’s lesser-known past as a plagiarizer. The zigzagging structure can feel disorienting at times, but these pivots feel purposefully zany: they show how wild yet interconnected such events are. In an early chapter, Young reviews Richard Adams Locke’s Great Moon Hoax, accounts of supposed lunar life published circa 1835 in The Sun, a paper that Locke also edited—getting to Stephen Glass, Jayson Blair, and other scandals that have plagued American journalism only some 300 pages later. Were these discussions siloed off into neat chapters, it might be easy to ascribe a strictly professional reason for why, say, mid-aughts memoirists were able to deceive editors and audiences so easily. But the method of distribution—print newspaper, Internet, memoir, porn—matters little in the history of the hoax. Young makes clear that our willingness to believe means the con begins in our own heads.

Bunk is filled with the sort of turns found in magic shows: the unexpected (though easily substantiated) connection is Young’s great trick. He shows us the history—now you see it—which we collectively forget—now you don’t. The nation’s quiet, furtive obsession with the conman, “a covert cultural hero,” reflects what he calls one of the foundational “discrepancies between our ideals and our conduct”: “Nowhere did nineteenth century America’s hypocrisy show itself, and hide itself, more completely than in chattel slavery,” he writes. “In a young country dedicated to liberty, here was a ‘peculiar institution’ that the Constitution could not speak of clearly, but euphemized instead.” That tendency toward habitual self-deception was foundational to American pop culture. One of Bunk’s inciting incidents is Barnum’s sideshow, which Young suggests began pop culture in the United States, together with the minstrel show. Its most prominent act involved Joice Heth, a black woman Barnum passed off as the 161-year-old former nursemaid of George Washington, who in actuality was an enslaved woman he’d purchased. Young applies the hoax concept to other incidents of American trickery in the centuries since. The Heth act was easily identifiable as untrue by most 1835 audiences, and stereotypes related to race, gender, and sexuality can be received in much the same way: something collectively understood as false but maintained anyway.

Young is poetry editor at The New Yorker and director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and his body of work, both as a poet and a scholar of black history, make him well-suited to engage this material. In the same way that Suzan-Lori Parks uses drama as an apt scalpel for history, Young uses creative nonfiction, often employing the same elegant puns and pivots that appear in his verse. Where Parks in her play Topdog/Underdog used three-card monte and the arcade as symbolic showcases for American violence and its bloody repetition, Young demonstrates in Bunk how the “con” works in more abstract ways. In the early twentieth century, the so-called long-con went from being perpetrated nomadically to taking place in a “store,” a semi-permanent set of displays meant to resemble a real shop that targets could visit repeatedly. His use of the conman’s “store” as a metaphor for America’s repository of dubious racial ideas and gender stereotypes is particularly insightful. Along with his winking approach to the material, his bemused attitude helps to detract from the horror, offering a model for processing current national affairs. Bunk suggests that one has to smirk at this stuff once in awhile, to avoid getting too freaked out.

Young’s compendium does have a noticeable gap. What about the counter-cons enacted by non-white people? What of passing for white, or the Internet folk who pass along Sophia Stewart out of an impulse to redress historical theft? For that, readers might turn to Young’s The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness (2011), where he writes about a tradition that he calls “storying,” a “counterfeit tradition” that he frames “not as mere distraction from oppression but as a derailing of it.” Although there is a mention of how the pioneering black nineteenth-century novelist Harriet Wilson utilized phony Spiritualism to subversive effect, Bunk offers no real contemporary examples of that kind of counter-ingenuity.

Yet this is a small gripe. Bunk is a consistently incisive look at the nature of American imposture and epistemology itself: How do we know what we know, how do we learn? How do we undo what we learn, and how do we avoid making the same mistakes? As of this writing, there’s a controversy regarding the PEN Awards and a writer, John Smelcer, pretending to be Native American. Joanne the Scammer is a cult hero, Catfish a hit TV show. As Young writes in the book’s epilogue, “This is the world we’ve made; one that we can only hope from here on out is not entirely made up.”