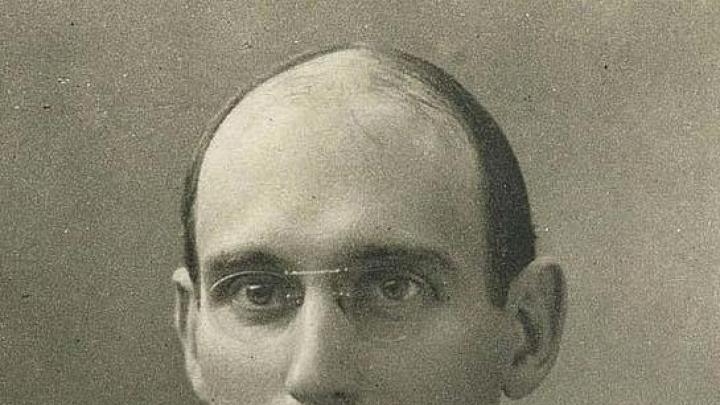

In August 1912, Harvard president emeritus Charles William Eliot addressed the Harvard Club of San Francisco on a subject close to his heart: racial purity. It was being threatened, he declared, by immigration. Eliot was not opposed to admitting new Americans, but he saw the mixture of racial groups it could bring about as a grave danger. “Each nation should keep its stock pure,” Eliot told his San Francisco audience. “There should be no blending of races.”

Eliot’s warning against mixing races—which for him included Irish Catholics marrying white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, Jews marrying Gentiles, and blacks marrying whites—was a central tenet of eugenics. The eugenics movement, which had begun in England and was rapidly spreading in the United States, insisted that human progress depended on promoting reproduction by the best people in the best combinations, and preventing the unworthy from having children.

The former Harvard president was an outspoken supporter of another major eugenic cause of his time: forced sterilization of people declared to be “feebleminded,” physically disabled, “criminalistic,” or otherwise flawed. In 1907, Indiana had enacted the nation’s first eugenic sterilization law. Four years later, in a paper on “The Suppression of Moral Defectives,” Eliot declared that Indiana’s law “blazed the trail which all free states must follow, if they would protect themselves from moral degeneracy.”

He also lent his considerable prestige to the campaign to build a global eugenics movement. He was a vice president of the First International Eugenics Congress, which met in London in 1912 to hear papers on “racial suicide” among Northern Europeans and similar topics. Two years later, Eliot helped organize the First National Conference on Race Betterment in Battle Creek, Michigan.

None of these actions created problems for Eliot at Harvard, for a simple reason: they were well within the intellectual mainstream at the University. Harvard administrators, faculty members, and alumni were at the forefront of American eugenics—founding eugenics organizations, writing academic and popular eugenics articles, and lobbying government to enact eugenics laws. And for many years, scarcely any significant Harvard voices, if any at all, were raised against it.

Harvard’s role in the movement was in many ways not surprising. Eugenics attracted considerable support from progressives, reformers, and educated elites as a way of using science to make a better world. Harvard was hardly the only university that was home to prominent eugenicists. Stanford’s first president, David Starr Jordan, and Yale’s most acclaimed economist, Irving Fisher, were leaders in the movement. The University of Virginia was a center of scientific racism, with professors like Robert Bennett Bean, author of such works of pseudo-science as the 1906 American Journal of Anatomy article, “Some Racial Peculiarities of the Negro Brain.”

But in part because of its overall prominence and influence on society, and in part because of its sheer enthusiasm, Harvard was more central to American eugenics than any other university. Harvard has, with some justification, been called the “brain trust” of twentieth-century eugenics, but the role it played is little remembered or remarked upon today. It is understandable that the University is not eager to recall its part in that tragically misguided intellectual movement—but it is a chapter too important to be forgotten.In part because of its overall prominence and influence on society, and in part because of its sheer enthusiasm, Harvard was more central to American eugenics than any other university.

Eugenics emerged in England in the late 1800s, when Francis Galton, a half cousin of Charles Darwin, began studying the families of some of history’s greatest thinkers and concluded that genius was hereditary. Galton invented a new word—combining the Greek for “good” and “genes”—and launched a movement calling for society to take affirmative steps to promote “the more suitable races or strains of blood.” Echoing his famous half cousin’s work on evolution, Galton declared that “what Nature does blindly, slowly, and ruthlessly, man may do providently, quickly, and kindly.”

Eugenics soon made its way across the Atlantic, reinforced by the discoveries of Gregor Mendel and the new science of genetics. In the United States, it found some of its earliest support among the same group that Harvard had: the wealthy old families of Boston. The Boston Brahmins were strong believers in the power of their own bloodlines, and it was an easy leap for many of them to believe that society should work to make the nation’s gene pool as exalted as their own.

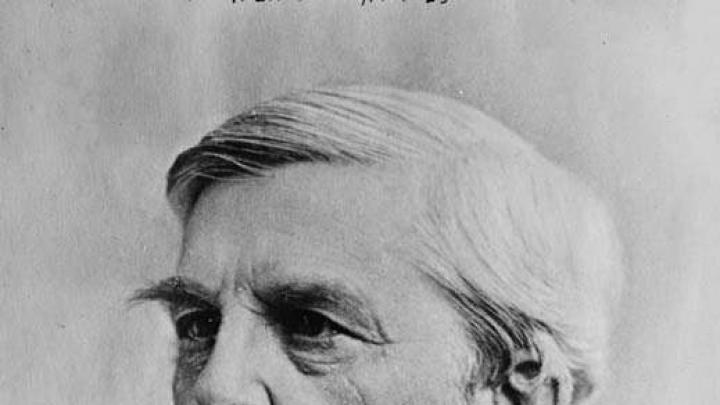

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.—A.B. 1829, M.D. ’36, LL.D. ’80, dean of Harvard Medical School, acclaimed writer, and father of the future Supreme Court justice—was one of the first American intellectuals to espouse eugenics. Holmes, whose ancestors had been at Harvard since John Oliver entered with the class of 1680, had been writing about human breeding even before Galton. He had coined the phrase “Boston Brahmin” in an 1861 book in which he described his social class as a physical and mental elite, identifiable by its noble “physiognomy” and “aptitude for learning,” which he insisted were “congenital and hereditary.”

Holmes believed eugenic principles could be used to address the nation’s social problems. In an 1875 article in The Atlantic Monthly, he gave Galton an early embrace, and argued that his ideas could help to explain the roots of criminal behavior. “If genius and talent are inherited, as Mr. Galton has so conclusively shown,” Holmes wrote, “why should not deep-rooted moral defects…show themselves…in the descendants of moral monsters?”

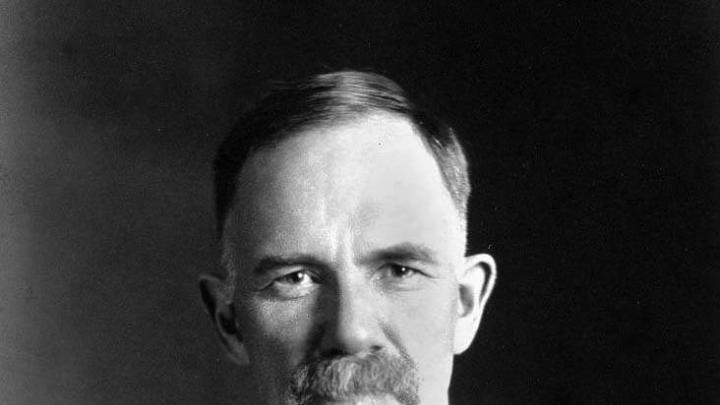

As eugenics grew in popularity, it took hold at the highest levels of Harvard. A. Lawrence Lowell, who served as president from 1909 to 1933, was an active supporter. Lowell, who worked to impose a quota on Jewish students and to keep black students from living in the Yard, was particularly concerned about immigration—and he joined the eugenicists in calling for sharp limits. “The need for homogeneity in a democracy,” he insisted, justified laws “resisting the influx of great numbers of a greatly different race.”

Lowell also supported eugenics research. When the Eugenics Record Office, the nation’s leading eugenics research and propaganda organization, asked for access to Harvard records to study the physical and intellectual attributes of alumni fathers and sons, he readily agreed. Lowell had a strong personal interest in eugenics research, his secretary noted in response to the request.

The Harvard faculty contained some of nation’s most influential eugenics thinkers, in an array of academic disciplines. Frank W. Taussig, whose 1911 Principles of Economics was one of the most widely adopted economics textbooks of its time, called for sterilizing unworthy individuals, with a particular focus on the lower classes. “The human race could be immensely improved in quality, and its capacity for happy living immensely increased, if those of poor physical and mental endowment were prevented from multiplying,” he wrote. “Certain types of criminals and paupers breed only their kind, and society has a right and a duty to protect its members from the repeated burden of maintaining and guarding such parasites.”

Harvard’s geneticists gave important support to Galton’s fledgling would-be science. Botanist Edward M. East, who taught at Harvard’s Bussey Institution, propounded a particularly racial version of eugenics. In his 1919 book Inbreeding and Outbreeding: Their Genetic and Sociological Significance, East warned that race mixing would diminish the white race, writing: “Races have arisen which are as distinct in mental capacity as in physical traits.” The simple fact, he said, was that “the negro is inferior to the white.”

East also sounded a biological alarm about the Jews, Italians, Asians, and other foreigners who were arriving in large numbers. “The early settlers came from stock which had made notable contributions to civilization,” he asserted, whereas the new immigrants were coming “in increasing numbers from peoples who have impressed modern civilization but lightly.” There was a distinct possibility, he warned, that a “considerable part of these people are genetically undesirable.”

In his 1923 book, Mankind at the Crossroads, East’s pleas became more emphatic. The nation, he said, was being overrun by the feebleminded, who were reproducing more rapidly than the general population. “And we expect to restore the balance by expecting the latter to compete with them in the size of their families?” East wrote. “No! Eugenics is sorely needed; social progress without it is unthinkable….”

East’s Bussey Institution colleague William Ernest Castle taught a course on “Genetics and Eugenics,” one of a number of eugenics courses across the University. He also published a leading textbook by the same name that shaped the views of a generation of students nationwide. Genetics and Eugenics not only identified its author as “Professor of Zoology in Harvard University,” but was published by Harvard University Press and bore the “Veritas” seal on its title page, lending the appearance of an imprimatur to his strongly stated views.

In Genetics and Eugenics, Castle explained that race mixing, whether in animals or humans, produced inferior offspring. He believed there were superior and inferior races, and that “racial crossing” benefited neither. “From the viewpoint of a superior race there is nothing to be gained by crossing with an inferior race,” he wrote. “From the viewpoint of the inferior race also the cross is undesirable if the two races live side by side, because each race will despise individuals of mixed race and this will lead to endless friction.”

Castle also propounded the eugenicists’ argument that crime, prostitution, and “pauperism” were largely due to “feeblemindedness,” which he said was inherited. He urged that the unfortunate individuals so afflicted be sterilized or, in the case of women, “segregated” in institutions during their reproductive years to prevent them from having children.

Like his colleague East, Castle was deeply concerned about the biological impact of immigration. In some parts of the country, he said, the “good human stock” was dying out—and being replaced by “a European peasant population.” Would “this new population be a fit substitute for the old Anglo-Saxon stock?” Castle’s answer: “Time alone will tell.”

One of Harvard’s most prominent psychology professors was a eugenicist who pioneered the use of questionable intelligence testing. Robert M. Yerkes, A.B. 1898, Ph.D. ’02, published an introductory psychology textbook in 1911 that included a chapter on “Eugenics and Mental Life.” In it, he explained that “the cure for race deterioration is the selection of the fit as parents.”

Yerkes, who taught courses with such titles as “Educational Psychology, Heredity, and Eugenics” and “Mental Development in the Race,” developed a now-infamous intelligence test that was administered to 1.75 million U.S. Army enlistees in 1917. The test purported to find that more than 47 percent of the white test-takers, and even more of the black ones, were feebleminded. Some of Yerkes’s questions were straightforward language and math problems, but others were more like tests of familiarity with the dominant culture: one asked, “Christy Mathewson is famous as a: writer, artist, baseball player, comedian.” The journalist Walter Lippmann, A.B. 1910, Litt.D. ’44, said the results were not merely inaccurate, but “nonsense,” with “no more scientific foundation than a hundred other fads, vitamins,” or “correspondence courses in will power.” The 47 percent feebleminded claim was an absurd result unless, as Harvard’s late professor of geology Stephen Jay Gould put it, the United States was “a nation of morons.” But the Yerkes findings were widely accepted and helped fuel the drives to sterilize “unfit” Americans and keep out “unworthy” immigrants.The Yerkes findings were widely accepted and helped fuel the drives to sterilize “unfit” Americans and keep out “unworthy” immigrants.

Another eugenicist in a key position was William McDougall, who held the psychology professorship William James had formerly held. His 1920 book The Group Mind explained that the “negro” race had “never produced any individuals of really high mental and moral endowments” and was apparently “incapable” of doing so. His next book, Is America Safe for Democracy (1921), argued that civilizations declined because of “the inadequacy of the qualities of the people who are the bearers of it”—and advocated eugenic sterilization.

Harvard’s embrace of eugenics extended to the athletic department. Dudley Allen Sargent, who arrived in 1879 to direct Hemenway Gymnasium, infused physical education at the College with eugenic principles, including his conviction that certain kinds of exercise were particularly important for female students because they built strong pelvic muscles—which over time could advantage the gene pool. In “giving birth to a child…no amount of mental and moral education will ever take the place of a large well-developed pelvis with plenty of muscular and organic power behind it,” Sargent stated. The presence of large female pelvises, he insisted, would determine whether “large brainy children shall be born at all.”

Sargent, who presided over Hemenway for 40 years, used his position as a bully pulpit. In 1914, he addressed the nation’s largest eugenic gathering, the Race Betterment Conference, in Michigan, at which one of the main speakers called for eugenic sterilization of the “worthless one tenth” of the nation. Sargent told the conference that, based on his “long experience and careful observation” of Harvard and Radcliffe students, “physical education…is one of the most important factors in the betterment of the race.”

If Harvard’s embrace of eugenics had somehow remained within University confines—as merely an intellectual school of thought—the impact might have been contained. But members of the community took their ideas about genetic superiority and biological engineering to Congress, to the courts, and to the public at large—with considerable effect.

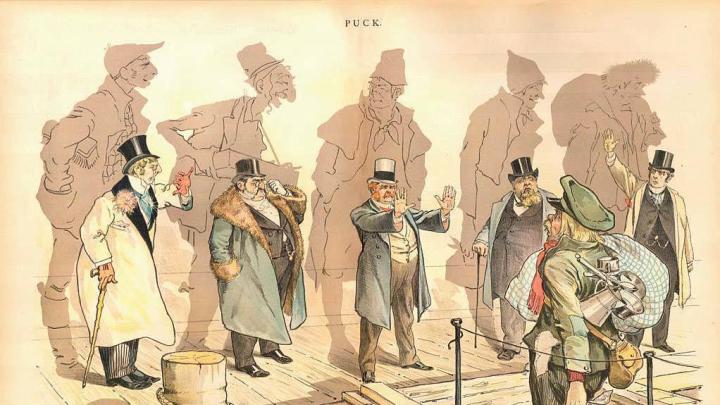

In 1894, a group of alumni met in Boston to found an organization that took a eugenic approach to what they considered the greatest threat to the nation: immigration. Prescott Farnsworth Hall, Charles Warren, and Robert DeCourcy Ward were young scions of old New England families, all from the class of 1889. They called their organization the Immigration Restriction League, but genetic thinking was so central to their mission that Hall proposed calling it the Eugenic Immigration League. Joseph Lee, A.B. 1883, A.M.-J.D. ’87, LL.D. ’26, scion of a wealthy Boston banking family and twice elected a Harvard Overseer, was a major funder, and William DeWitt Hyde A. B. 1879, S.T.D. ’86, another future Overseer and the president of Bowdoin College, served as a vice president. The membership rolls quickly filled with hundreds of people united in xenophobia, many of them Boston Brahmins and Harvard graduates.

Their goal was to keep out groups they regarded as biologically undesirable. Immigration was “a race question, pure and simple,” Ward said. “It is fundamentally a question as to…what races shall dominate in the country.” League members made no secret of whom they meant: Jews, Italians, Asians, and anyone else who did not share their northern European lineage.

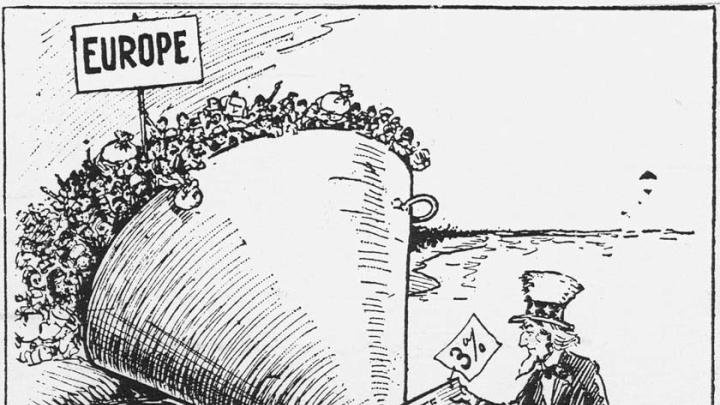

Drawing on Harvard influence to pursue its goals—recruiting alumni to establish branches in other parts of the country and boasting President Lowell himself as its vice president—the Immigration Restriction League was remarkably effective in its work. Its first major proposal was a literacy test, not only to reduce the total number of immigrants but also to lower the percentage from southern and eastern Europe, where literacy rates were lower. In 1896the league persuaded Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, A.B. 1871, LL.B. ’74, Ph.D. ’76, LL.D. ’04, to introduce a literacy bill. Getting it passed and signed into law took time, but beginning in 1917, immigrants were legally required to prove their literacy to be admitted to the country.

The league scored a far bigger victory with the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924. After hearing extensive expert testimony about the biological threat posed by immigrants, Congress imposed harsh national quotas designed to keep Jews, Italians, and Asians out. As the percentage of immigrants from northern Europe increased significantly, Jewish immigration fell from 190,000 in 1920 to 7,000 in 1926; Italian immigration fell nearly as sharply; and immigration from Asia was almost completely cut off until 1952.

While one group of alumni focused on inserting eugenics into immigration, another prominent alumnus was taking the lead of the broader movement. Charles Benedict Davenport, A.B. 1889, Ph.D. ’92, taught zoology at Harvard before founding the Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, in 1910. Funded in large part by Mrs. E.H. Harriman, widow of the railroad magnate, the E.R.O. became a powerful force in promoting eugenics. It was the main gathering place for academics studying eugenics, and the driving force in promoting eugenic sterilization laws nationwide.Davenport explained that qualities like criminality and laziness were genetically determined.

Davenport wrote prolifically. Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, published in 1911,quickly became the standard text for the eugenics courses cropping up at colleges and universities nationwide, and was cited by more than one-third of high-school biology textbooks of the era. Davenport explained that qualities like criminality and laziness were genetically determined. “When both parents are shiftless in some degree,” he wrote, only about 15 percent of their children would be “industrious.”

But perhaps no Harvard eugenicist had more impact on the public consciousness than Lothrop Stoddard, A.B. 1905, Ph.D. ’14. His bluntly titled 1920 bestseller, The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy, had 14 printings in its first three years, drew lavish praise from President Warren G. Harding, and made a mildly disguised appearance in The Great Gatsby, when Daisy Buchanan’s husband, Tom, exclaimed that “civilization’s going to pieces”—something he’d learned by reading “‘The Rise of the Colored Empires’ by this man Goddard.”

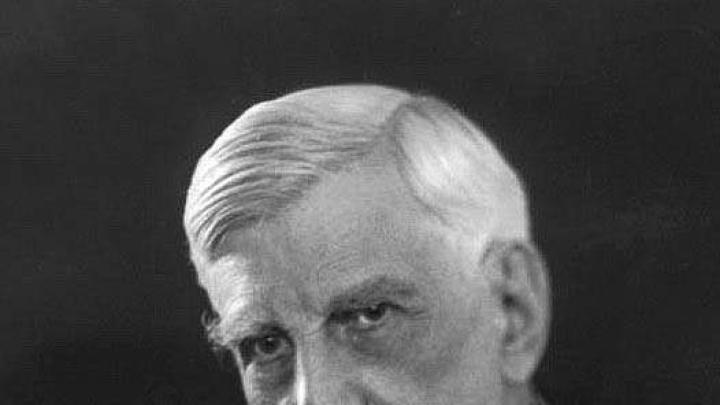

When eugenics reached a high-water mark in 1927, a pillar of the Harvard community once again played a critical role. In that year, the Supreme Court decided Buck v. Bell, a constitutional challenge to Virginia’s eugenic sterilization law. The case was brought on behalf of Carrie Buck, a young woman who had been designated “feebleminded” by the state and selected for eugenic sterilization. Buck was, in fact, not feebleminded at all. Growing up in poverty in Charlottesville, she had been taken in by a foster family and then raped by one of its relatives. She was declared “feebleminded” because she was pregnant out of wedlock, and she was chosen for sterilization because she was deemed to be feebleminded.

By an 8-1 vote, the justices upheld the Virginia law and Buck’s sterilization—and cleared the way for sterilizations to continue in about half the country, where there were similar laws. The majority opinion was written by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., A.B. 1861, LL.B. ’66, LL.D. ’95, a former Harvard Law School professor and Overseer. Holmes, who shared his father’s deep faith in bloodlines, did not merely give Virginia a green light: he urged the nation to get serious about eugenics and prevent large numbers of “unfit” Americans from reproducing. It was necessary to sterilize people who “sap the strength of the State,” Holmes insisted, to “prevent our being swamped with incompetence.” His opinion included one of the most brutal aphorisms in American law, saying of Buck, her mother, and her perfectly normal infant daughter: “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

In the same week the Supreme Court decided Buck v. Bell, Harvard made eugenics news of its own. It turned down a $60,000 bequest from Dr. J. Ewing Mears, a Philadelphia surgeon, to fund instruction in eugenics “in all its branches, notably that branch relating to the treatment of the defective and criminal classes by surgical procedures.”

Harvard’s decision, reported on the front page of The New York Times, appeared to be a counterweight to the Supreme Court’s ruling. But the University’s decision had been motivated more by reluctance to be coerced into a particular position on sterilization than by any institutional opposition to eugenics—which it continued to embrace.

Eugenics followed much the same arc at Harvard as it did in the nation at large. Interest began to wane in the 1930s, as the field became more closely associated with the Nazi government that had taken power in Germany. By the end of the decade, Davenport had retired and the E.R.O. had shut down; the Carnegie Institution, of which it was part, no longer wanted to support eugenics research and advocacy. As the nation went to war against a regime that embraced racism, eugenics increasingly came to be regarded as un-American.

It did not, however, entirely fade away—at the University, or nationally. Earnest Hooton, chairman of the anthropology department, was particularly outspoken in support of what he called a “biological purge.” In 1936, while the first German concentration camps were opening, he made a major plea for eugenic sterilization—though he emphasized that it should not target any race or religion.

Hooton believed it was imperative for society to remove its “worthless” people. “Our real purpose,” he declared in a speech that was quoted in The New York Times, “should be to segregate and to eliminate the unfit, worthless, degenerate and anti-social portion of each racial and ethnic strain in our population, so that we may utilize the substantial merits of its sound majority, and the special and diversified gifts of its superior members.”“Our real purpose…should be to segregate and to eliminate the unfit, worthless, degenerate and anti-social portion of each racial and ethnic strain in our population, so that we may utilize the substantial merits of its sound majority….”

None of the news out of Germany after the war made Hooton abandon his views. “There can be little doubt of the increase during the past fifty years of mental defectives, psychopaths, criminals, economic incompetents and the chronically diseased,” he wrote in Redbook magazine in 1950. “We owe this to the intervention of charity, ‘welfare’ and medical science, and to the reckless breeding of the unfit.”

The United States also held onto eugenics, if not as enthusiastically as it once did. In 1942, with the war against the Nazis raging, the Supreme Court had a chance to overturn Buck v. Bell and hold eugenic sterilization unconstitutional, but it did not. The court struck down an Oklahoma sterilization law, but on extremely narrow grounds—leaving the rest of the nation’s eugenic sterilization laws intact. Only after the civil-rights revolution of the 1960s, and changes in popular views toward marginalized groups, did eugenic sterilization begin to decline more rapidly. But states continued to sterilize the “unfit” until 1981.

Today, the American eugenics movement is often thought of as an episode of national folly—like 1920s dance marathons or Prohibition—with little harm done. In fact, the harm it caused was enormous.

As many as 70,000 Americans were forcibly sterilized for eugenic reasons, while important members of the Harvard community cheered and—as with Eliot, Lowell, and Holmes—called for more. Many of those 70,000 were simply poor, or had done something that a judge or social worker didn’t like, or—as in Carrie Buck’s case—had terrible luck. Their lives were changed forever—Buck lost her daughter to illness and died childless in 1983, not understanding until her final years what the state had done to her, or why she had been unable to have more children.

Also affected were the many people kept out of the country by the eugenically inspired immigration laws of the 1920s. Among them were a large number of European Jews who desperately sought to escape the impending Holocaust. A few years ago, correspondence was discovered from 1941 in which Otto Frank pleaded with the U.S. State Department for visas for himself, his wife, and his daughters Margot and Anne. It is understood today that Anne Frank died because the Nazis considered her a member of an inferior race, but few appreciate that her death was also due, in part, to the fact that many in the U.S. Congress felt the same way.

There are important reasons for remembering, and further exploring, Harvard’s role in eugenics. Colleges and universities today are increasingly interrogating their pasts—thinking about what it means to have a Yale residential college named after John C. Calhoun, a Princeton school named after Woodrow Wilson, or slaveholder Isaac Royall’s coat of arms on the Harvard Law School shield and his name on a professorship endowed by his will.

Eugenics is a part of Harvard’s history. It is unlikely that Eliot House or Lowell House will be renamed, but there might be a way for the University community to spare a thought for Carrie Buck and others who paid a high price for the harmful ideas that Harvard affiliates played a major role in propounding.

There are also forward-looking reasons to revisit this dark moment in the University’s past. Biotechnical science has advanced to the brink of a new era of genetic possibilities. In the next few years, the headlines will be full of stories about gene-editing technology, genetic “solutions” for a variety of human afflictions and frailties, and even “designer babies.” Given that Harvard affiliates, again, will play a large role in all of these, it is important to contemplate how wrong so many people tied to the University got it the first time—and to think hard about how, this time, to get it right.