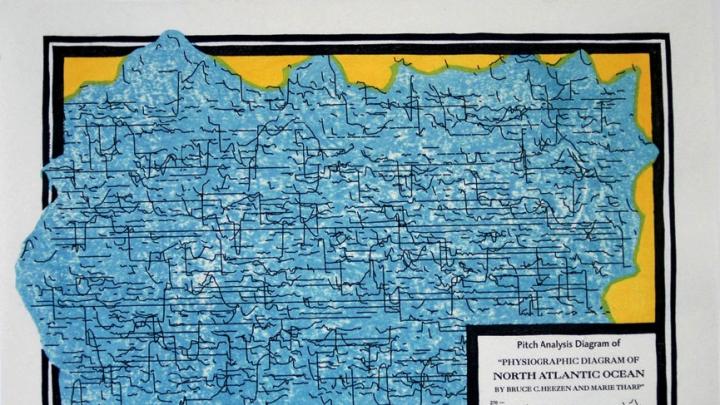

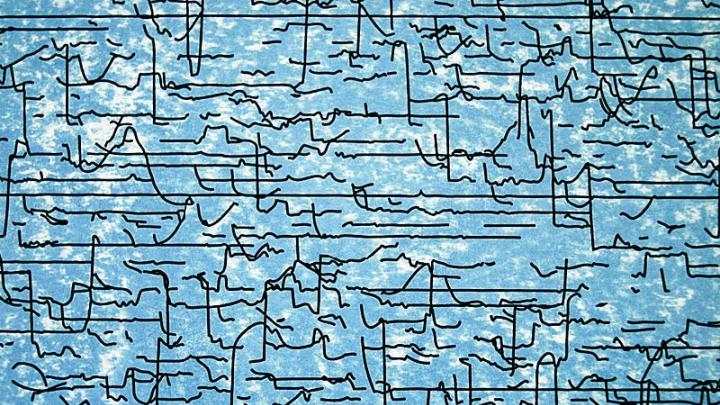

Despite its muted color palettes and simple shapes and lines, the art of Sarah Hulsey ’01 has a lot to say. Nearly every piece—each screen print, relief print, etching, or artist’s book—features letterpress text of some kind. It’s not prose, nor is it poetry, and its presence can be confusing. Though the visuals may be mystifying at first, patterns start to emerge, reminiscent of familiar objects: road maps, line graphs, or the periodic table of elements. Hulsey’s graphic images are characterized by a sense of careful handicraft: boxes may not be perfect squares, but they are aligned. Recent sources of inspiration include audio recordings of ocean floor maps and Copernicus’s drawings of heliocentric solar systems: diagrams, charts, and objects she describes as “really gorgeous, graphical things, apart from whatever they’re conveying.” The same could be said of Hulsey’s own pieces—but knowing what information they convey, and her meticulous intellectual approach, makes them all the more captivating.

Hulsey can detail the concepts behind her artwork, but she struggles to describe its aesthetics. “I don’t fully speak the same language as people who are more scholarly in the art world,” she says. Instead, her vocabulary stems from linguistics itself. The systems and components that make up language and art draw her to both disciplines. Language is composed of parts that fit together in a particular manner: words are ordered in certain ways to form sentences; roots, prefixes, and suffixes fit together to form words. Likewise, movable type on a letterpress must be arranged in a particular manner; books are structured into groupings of lines, pages, chapters, volumes, editions, and series. By appropriating the visual style of diagrams, maps, and charts, Hulsey’s pieces marry the craft and rigor of conceptual art with the graphic pop of information design, to edge toward fresh takes on communication itself. Language, she explains, “is this really elaborate structure that speakers are, for all intents and purposes, totally unaware of”—and her work explores the subtle intricacies that make speech make sense.

When she first pursued printmaking, Hulsey considered it a side interest, completely separate from her academic studies. A linguistics concentrator at Harvard, she worked at the Fogg Art Museum as an art handler under print curator Marjorie Cohn, took a screen-printing class, and learned letterpress at Bow and Arrow Press in Adams House. After graduation, she attended workshops and courses on letterpress printing, papermaking, and bookbinding. While earning her Ph.D. in linguistics at MIT, she kept a studio in nearby Somerville to pursue her hobby. Ten years and one M.F.A. from the University of the Arts (in Philadelphia) later, she has left the world of academic linguistics but still works in the same studio, pursuing her intellectual interests through artistic practice.

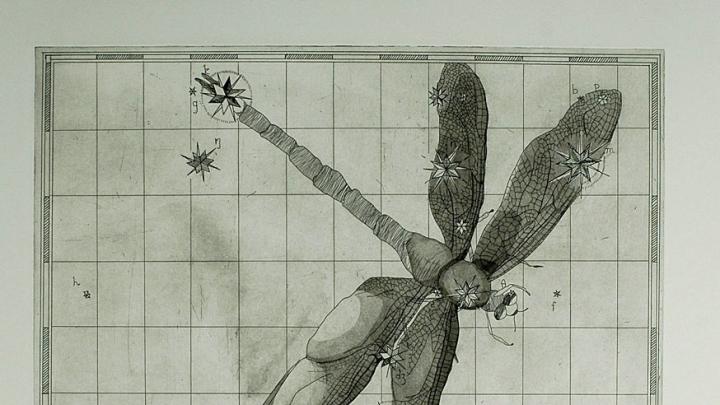

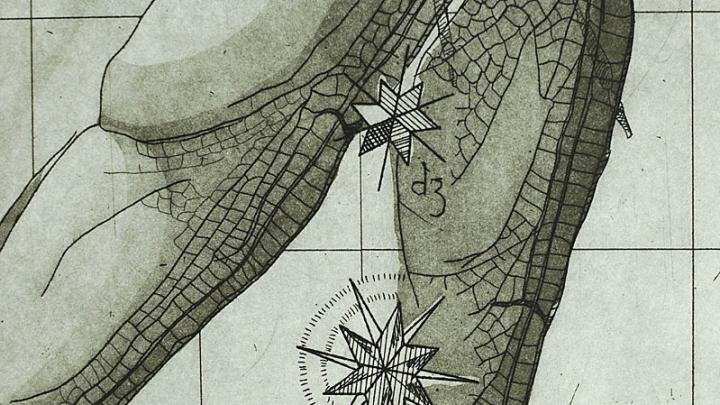

Currently, Hulsey is mapping the words in seventeenth-century astronomy books brought to her attention by a curator at the Huntington Library in Los Angeles. Her creative process has three parts: “There’s the aesthetic, visual place where it starts, and then the conceptual part of it is largely analytical, and then there’s the manual, craft production of it.” Typically, she begins with a visual inspiration, like a star chart, that guides the graphic identity or overarching style of the piece. She then examines an accompanying text to figure out how its language follows rules and exhibits patterns, whether of word frequency, pitch of sound, or lexical relations. Finally, she depicts her linguistic analyses in the same visual vein as the original diagram—in this series, by using intaglio printing (in which an image is etched onto a plate and the incision holds the ink)in the fashion of the star charts, which map constellations, that appear in the books.

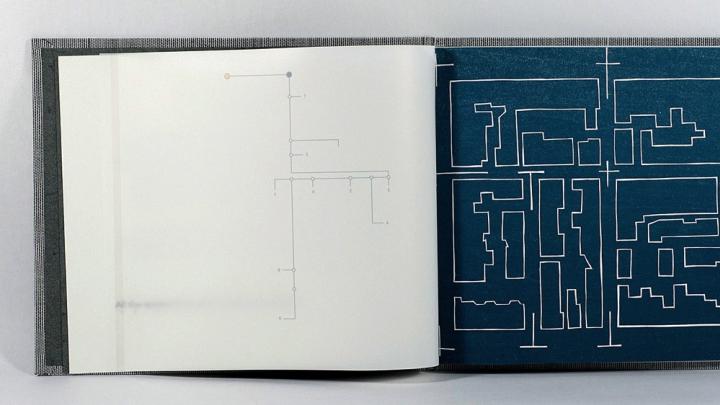

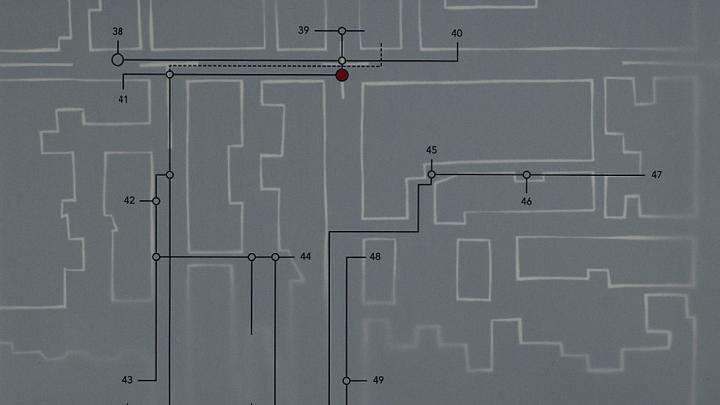

Her recent work The Space of Poetics is an artist’s book (a handmade art object, one of a kind or printed in small editions) made with woodcut and letterpress. It diagrams a paragraph from French philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s treatise The Poetics of Space, a work that considershow people inhabit physical spaces, and how that affects their experiences and memories. To show the syntactical relationships in the excerpt, Hulsey uses imagery gleaned from the 32-volume Sanborn Fire Insurance Atlas of Philadelphia of 1916, which collects grid plans of all the city’s blocks, color-coded by building material, updated by hand over the years. Just as syntax connects the words in Bachelard’s writing, rooms are linked in electrical wiring diagrams and blueprints.

Hulsey’s process may sound intimidating, and her subject matter esoteric. Yet the resulting prints are playful, prompting creative interpretation from viewers whether or not they understand the linguistic underpinnings. But unlike traditional maps, or the infographics pervasive in today’s media, her art does not merely communicate data points in a pleasing way. Instead, as she puts it, “The former linguist in me hopes that as a body, the work will inspire a little bit of awe at how elaborate and complicated the linguistics system is.” By visually investigating elements of language, Hulsey’s art compels viewers to look harder, listen better, and notice more. A picture is worth a thousand words, but her works speak in their own way.