The University’s endowment was valued at $37.6 billion on last June 30, the end of fiscal year 2015—a gain of $1.2 billion (3.3 percent) from a year earlier—finally exceeding the peak value (not adjusted for inflation) realized in fiscal 2008, just before the financial crisis. The fiscal 2015 appreciation reflects investment returns during the year (perhaps $2.0 to $2.2 billion—exact figures appear later this fall in Harvard’s annual financial report), minus distributions for the University’s operating budget and other purposes (perhaps $1.6 billion), plus gifts received as The Harvard Campaign proceeds (see “$6 Billion-Plus”).

But that nominal achievement was overshadowed by the relatively modest 5.8 percent rate of return on the assets invested by or under the purview of Harvard Management Company (HMC). In a September 22 letter announcing the results, Stephen Blyth, HMC’s president and CEO since last January, starkly outlined the endowment’s diminishing investment margin relative to its market benchmarks; its recent performance (lagging several peer institutions’ funds); and new objectives and strategies intended to improve performance consistent with the endowment’s role in financing Harvard’s “preeminence in teaching, learning, and research,” as his new HMC mission statement puts it.

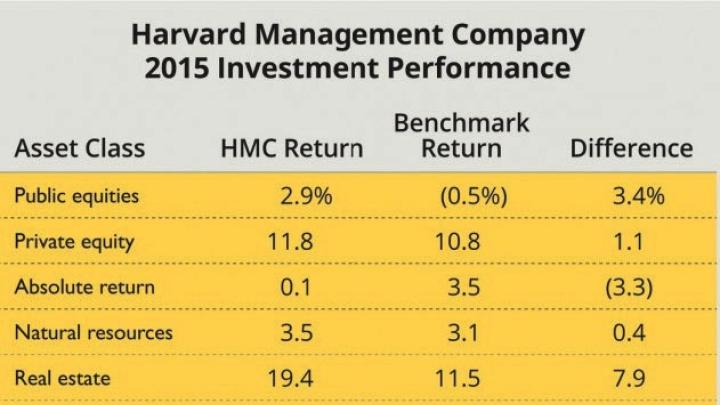

Given the relatively challenging investment environment, the 5.8 percent return (after expenses) trailed the 15.4 percent return HMC realized in fiscal 2014. Real-estate and private-equity assets contributed disproportionately to the gains (see chart); holdings of public stocks produced modestly positive returns, as U.S. equities appreciated (up 12.4 percent), but foreign and emerging-market portfolios produced losses. The buffering expected from absolute-return (hedge-fund) holdings was barely realized, clearly a disappointing underperformance.

Citing an expectation that the endowment should outperform market returns by at least 1 percent on a rolling five-year average annualized basis, Blyth observed that HMC did well from fiscal 2000 through 2008, beating its benchmarks by 3.8 to 6.5 percentage points. But that margin declined thereafter—falling short of the one-point margin in fiscal 2012 and 2013, and averaging only about 1.1 percent during the past six years.

He reported that among a cohort of 10 other universities with managed assets ranging from $25 billion down to $9 billion, HMC’s performance (measured on the five-year basis) fell in the second quartile from fiscal 2000 through 2003; rose to the first quartile from 2004 through 2008; declined to the third quartile during the financial crisis and recession in 2009-2010; and declined further, to the last quartile, from 2011 through 2014. Different rates of return on huge endowments ultimately translate into a difference of hundreds of millions in funds available to support institutions’ academic and operating budgets. HMC’s 10-year annualized rate of return is now 7.6 percent, its 20-year figure 11.8 percent; for Yale, the comparable rates of return are 10 percent and 13.7 percent.

Blyth called it “unlikely that our return in…2015 will materially improve our performance relative to our endowment peer group”—and among larger institutions reporting, MIT realized a 13.2 percent return for fiscal 2015, Princeton 12.7 percent, Stanford 7 percent, and Yale 11.5 percent. Yale’s investment professionals managed gains of $2.6 billion—likely more than HMC realized on a pool of assets more than 50 percent larger—and so were able to increase the value of their endowment by 7.1 percent, to $25.6 billion, after distributions for their university’s budget. (Both Harvard and Yale derive about one-third of operating revenues from endowment distributions.)

That rate of asset growth, propelled by investment returns, is what counts. Blyth’s critical objective for HMC is “to achieve a real return of 5 percent or more, with inflation measured by the Higher Education Price Index (HEPI) on a rolling 10-year annualized basis.” The current 10-year annualized inflation measured by HEPI is 2.7 percent—making HMC’s target 7.7 percent. On the evidence, achieving that won’t be easy. (It actually exceeds the 7.4 percent goal HMC articulated a year earlier.) But as Blyth pointed out, “real returns have declined steadily over time,” given low interest rates, greater investor interest in diverse asset classes (lowering returns as more money flows in), and so on. Accordingly, he continued, “Delivering a real return of 5 percent will be more challenging in the current environment than in the past.”

In pursuit of that outcome, Blyth outlined:

• a new, analytical approach to asset allocation, intended to be more flexible and inter-sectoral than HMC’s traditional “policy portfolio.” The new approach gives broad ranges for investment commitments among the many asset classes; for example, compared to the past goal of 11 percent allocations each to U.S., foreign, and emerging-market equities, the 2016 ranges are, respectively, 6 percent to 16 percent; 6 percent to 11 percent; and 4 percent to 17 percent. (For readily traded assets like stocks and public bonds, it is easy to see how such wide ranges could be accommodated annually. It is less clear how HMC would effect comparably large swings in allocations to illiquid assets—private equity, hedge funds, natural-resources holdings, and real estate—where the model envisions ranges of up to 10 percent: more than $3 billion at the current endowment size.)

• a more nimble investment process. Blyth sketched collaboration and cross-asset-class investments taking advantage of the HMC staff’s aggregate knowledge.

• and, always an issue for HMC, with a significant share of assets under internal management by highly paid professionals, a revised compensation system that would apparently tie incentive pay not only to each portfolio’s outperformance relative to its asset class, but also to HMC’s aggregate performance on Harvard’s behalf, in keeping with the mission statement.

Some of the affected personnel will be different. HMC announced that Andrew Wiltshire, head of alternative investments (and the leader of successful timberland investing), is retiring later this year, and Alvaro Aguirre-Simunovic, natural-resources portfolio manager, departed as of October 9; both were among HMC’s most highly compensated staff based on past performance (see harvardmag.com/pays-15), but Blyth characterized fiscal 2015 natural-resources returns as “generally subdued.” On October 2, it became known that Marco Barrozo, head of fixed income, and Satu Parikh, who had just taken over natural resources, had also departed, and that their respective investment portfolios had “been unwound.”

(Boosting results for private-equity and absolute-return investments, where peers have consistently outperformed, will be important to HMC. The recent addition to its board of directors of Joshua Friedman ’76, M.B.A. ’80, J.D. ’82, co-founder and co-CEO of the Canyon Partners hedge fund, and Safra professor of economics Jeremy Stein, who consults with another hedge fund, may provide useful insights.)

Blyth offered a cautious outlook, citing increased market volatility during the past year; changing regulation of financial institutions; the impact of “the eventual rise of interest rates” in the United States; and seemingly high valuations for private-equity and venture-capital investments—an “environment…likely to result in lower future returns than in the recent past.”

He concluded on a personal note, emphasizing that “I know that my colleagues…share deeply the special role that HMC plays in the support of our great University.

“We have…laid out straightforward, ambitious investment objectives.…We have challenges ahead and much hard work to be done, but I believe we have gained significant traction in 2015, and I am highly optimistic that we can achieve our goals.”

Read a full report at harvardmag.com/endowment-15.