- The endowment’s value stood at $37.6 billion as of June 30, the end of fiscal year 2015—finally exceeding the nominal peak value (not adjusted for inflation) of $36.9 billion realized in fiscal year 2008, just before the financial crisis and ensuing recession. The new total represents a gain of $1.2 billion (3.3 percent) from $36.4 billion a year earlier.

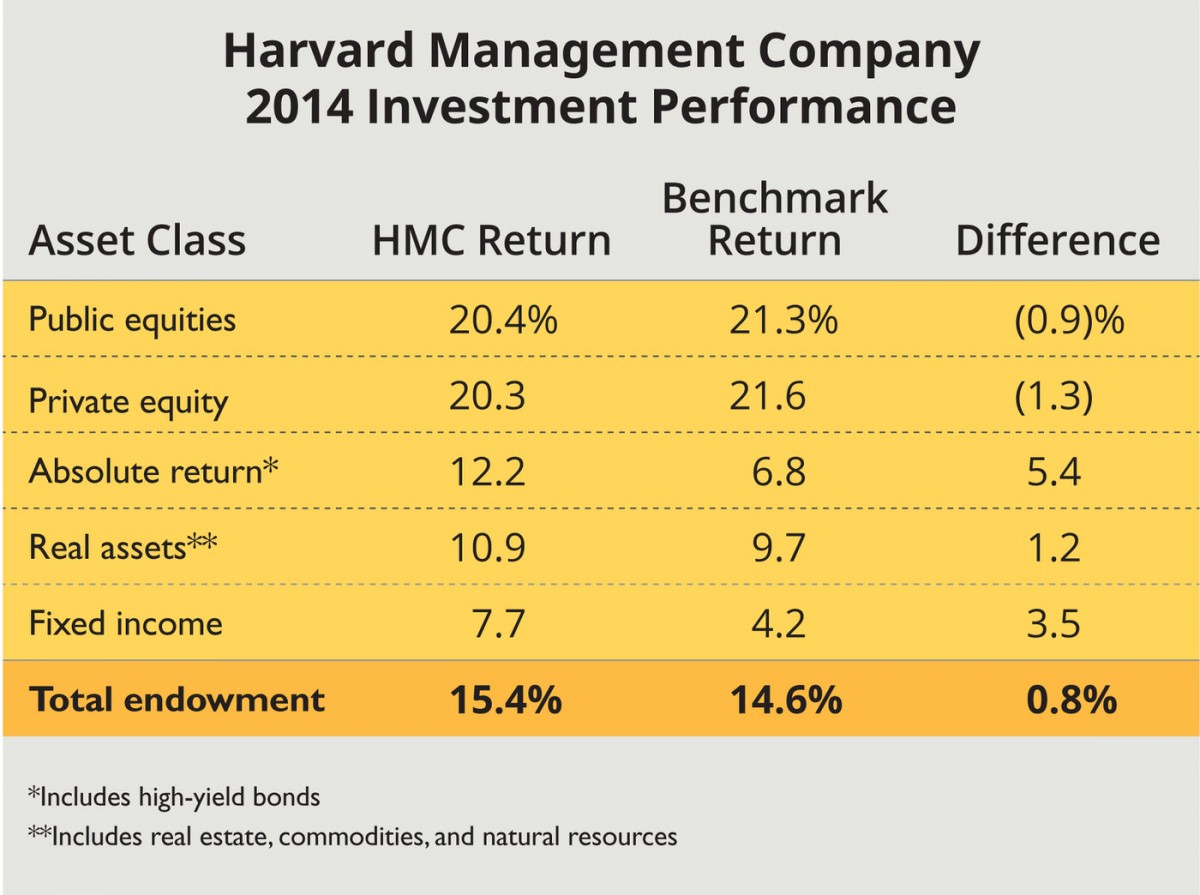

- Amid more challenging conditions in world financial markets during the fiscal year, Harvard Management Company recorded a 5.8 percent investment return on endowment assets during fiscal 2015, down from a 15.4 percent return in the prior year. These results are broadly in line with expectations based on the results of other institutional investment funds released during the summer, as previously reported. Nevertheless, they lag the endowment’s previously articulated goal of earning an “expected long-term return of 7.4 percent” (see the discussion of new goals below).

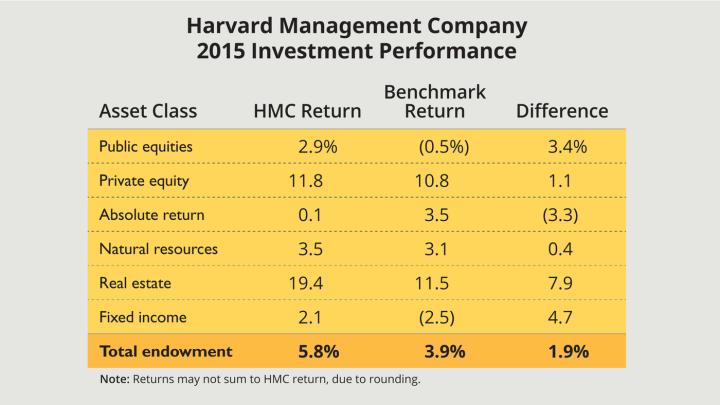

- Private-equity and real-estate assets led positive returns; foreign and emerging-market stocks produced losses; and all classes of assets except absolute return (hedge funds) exceeded returns realized by market benchmarks for each class.

- Harvard’s overall performance exceeded the 3.9 percent return of its benchmark policy portfolio (its asset-allocation model) by 190 basis points. It is early in the reporting season, but Harvard’s results trailed those reported by MIT, Stanford, and the University of Virginia, among institutions with sophisticated portfolios and investment strategies (see below).

- The management company’s senior leadership team spelled out significant changes in how it describes its long-term investment objectives, asset allocation, and performance goals, with a tough critique of its past returns and performance relative to large-university peers (see below).

The University continues to set a torrid pace in raising money—The Harvard Crimson recently reported that the Harvard Campaign had recorded gifts and pledges exceeding $6 billion (toward its announced goal of $6.5 billion) as of the end of the fiscal year. But the single most significant determinant of the institution’s financial health remains the condition of the endowment, as even modest investment returns yield large sums in absolute terms, underpinning Harvard’s largest source of operating income (distributions from the endowment were $1.54 billion, or 35 percent of the University’s $4.41 billion of revenue, in fiscal 2014, the most recent year reported).

The Harvard Management Company (HMC), which invests the endowment and other University financial assets, today reported that the endowment’s value rose 3.3 percent, to $37.6 billion, as of the end of the fiscal year, this past June 30. That compares to an 11.3 percent gain in the endowment’s value during fiscal 2014.

The report is the first since Stephen Blyth (formerly HMC’s head of public markets) became president and chief executive officer last January 1, succeeding Jane L. Mendillo—and thus represents the results of a transition year. Given the multiple classes of assets in HMC’s portfolios and the illiquid nature of many of its private investments, decisions by Blyth and his team—and they appear significant—are just beginning to be implemented; their effects will emerge over an extended period. But he devoted much of his first annual report to detailing major changes in how HMC operates.

In absolute terms, the endowment’s value increased $1.2. billion, consistent with a back-of-the-envelope calculation prepared several weeks ago, attaining a new peak value above the $36.9 billion reported in June 2008, just before the financial crisis.

The growth during the year just ended represents the interaction of three factors:

Appreciation. HMC’s in-house and external money managers earned an aggregate 5.8 percent investment return on endowment assets (after all expenses) during fiscal 2015. That produced perhaps $2 billion to $2.2 billion in gains (disregarding other transfers and timing differences that go into the final rate-of-return calculation and reported endowment value). In recent prior years the rates of return were as follows, illustrating both the magnitude of endowment appreciation (after large distributions to support the University operating budget, discussed immediately below) when investment returns are strong, and the volatility of those returns:

- Fiscal 2014: 15.4 percent (year-end value $36.4 billion)

- Fiscal 2013: 11.3 percent (year-end value $32.7 billion)

- Fiscal 2012: (0.05) percent (year-end value $30.7 billion)

- Fiscal 2011: 21.4 percent (year-end value $32 billion)

- Fiscal 2010: 11.0 percent (year-end value $27.4 billion)

Distributions. The endowment’s value is reduced by distributions to support Harvard’s operating budget, and other distributions for one-time purposes (“decapitalizations”). The operating distributions totaled $1.54 billion in fiscal 2014, and were budgeted to increase about three percent this past year. They likely grew somewhat more, reflecting distributions on various transferred funds and new monies received, so an estimate of $1.6 billion in fiscal 2015 distributions might be in order. Decapitalizations, which vary widely from year to year, were $241 million in fiscal 2014. (Comparable figures for fiscal 2015 become available when the University’s annual financial report is published later this autumn.)

Gifts. Finally, the endowment’s value is augmented by capital gifts received for the endowment during the year. That sum totaled $513 million in fiscal 2014 (more than double the fiscal 2013 sum)—reflecting the proceeds from the campaign. And there is a long runway, too: the annual financial report showed total pledges receivable of $1.59 billion at the end of fiscal 2014, up a healthy 29 percent from the prior year—pledges that gradually turn into gift proceeds, whether for near-term use or as endowment balances. (Pledges specifically for the endowment constituted $546 million of that $1.59 billion as of June 30, 2014.) Again, the exact figure will be released with Harvard’s fiscal 2015 financial report sometime later this autumn.

Thus, the rough arithmetic would be: $36.4 billion beginning value plus $2.0 to $2.2 billion (fiscal 2015 investment gains), minus $1.6 billion (distributions for the University budget), plus some gifts for endowment received, equal the endowment’s $37.6-billion value as of this past June 30.

The Investment Context

The financial-market conditions that supported strong returns in fiscal 2014 were less favorable around the world this past year. For equity investors, global market indexes registered about a 1.2 percent gain in fiscal 2015; the Standard & Poor’s 500 index of large-capitalization U.S. stocks appreciated 7.2 percent, but the strengthening dollar penalized U.S. investors’ returns in developed overseas markets, generating negative returns; and the emerging-markets indexes declined about 5 percent in dollar terms, reflecting economic weakness in China, Brazil, and other areas. In the fixed-income sector, global bond indexes showed returns of perhaps 2 to 3 percent, with continued low interest rates in much of the world. Commodities prices collapsed, driven by the disrupted oil market and the slowing of demand in China.

HMC has substantial assets in these categories, as well as investments in private equity and real estate—the standout performers among all asset classes this year—and other holdings (see the charts above and below, which differ given a new reporting format this year, and the narrative in “Harvard Performance Details,” below).

A traditional 60/40 portfolio (60 percent equities and 40 percent bonds, using broad public-market benchmarks—unlike Harvard’s and other diversified university endowments, which rely much more heavily on private assets) yielded low single-digit returns for the year. Wilshire Associates’ Trust Universe Comparison Service—a common benchmark for endowment and foundation investors, many of whom have assets that look like the traditional 60/40 model—showed a median one-year return of 3.2 percent for funds with more than $1 billion of assets (and 4 percent for the largest quartile), and 2.7 percent for smaller funds.

It is early in the annual reporting season (most peers with large, diversified endowment portfolios, including Yale and Princeton, have yet to publish results), but the results to date are indicative of what kind of year investors had. Among higher-education institutions, the following reported these rates of returns during the fiscal year, and the resulting values of their endowments:

- Bowdoin: an eye-popping 14.4 percent, on its smaller, $1.4-billion endowment

- MIT: 13.2 percent, $13.5 billion—a strong candidate for strongest performance among the larger institutions’ endowments

- University of Virginia: 7.7 percent, $7.5 billion (The University of Virginia Investment Management Company, which has a very strong long-term record and excellent, detailed financial reporting, highlighted exceptional results in the growth-equity and venture parts of its private-equity portfolio (32.9 percent and 42.0 percent respectively, bringing private-equity returns as a whole to 25.8 percent), and private real-estate investments, up 21.8 percent.

- Stanford: 7 percent, $22.2 billion

Among public institutions, the following offered interesting commentary on their results:

- The huge California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) reported preliminary fiscal 2015 returns of 2.4 percent, down from 18.4 percent in 2014 and 12.5 percent in 2013 (when HMC’s returns were, as noted above, 15.4 percent and 11.3 percent, respectively). CalPERS cited strong investment results for real estate (approximately 13.5 percent) and private equity (8.9 percent)—both valued as of March 31. Another category of tangible assets, forestland (an asset HMC has emphasized in recent years), produced a slightly negative return. “Global equity,” CalPERS's stock investments, yielded 1 percent, in the face of “the strengthening of the U.S. dollar versus most foreign currencies, as well as challenging emerging-market local returns.” Fixed-income assets (public bonds), earned a 1.3 percent return.

- The Massachusetts state pension fund reported 3.9 percent returns for fiscal 2015, down from 17.6 percent and 12.7 percent in the prior two years. Real estate (12 percent return) and private equity (15.6 percent) were the stand-out categories. U.S. stocks returned 6.8 percent, but developed-economy foreign stock returns were negative 2.8 percent and emerging-market stocks were weaker still, returning negative 5.9 percent. Fixed-income returns varied by strategy, from positive 4.7 percent to negative 4.7 percent. Timber and natural-resources holdings (which may include assets in the very weak energy sector) returned a negative 1.4 percent, and hedge funds (often included in portfolios to counter market returns) produced a positive return of 3.7 percent.

Harvard Performance Details

Fiscal 2014 was a banner year for stock investors. This year, the honors went to investors in private assets.

Public equities. Public stock investments—traditionally about one-third of HMC’s assets—produced aggregate returns of 2.9 percent, exceeding the negative market (benchmark) return of (0.5 percent). Blyth’s letter disaggregates the performance:

- U.S. equities returned 12.4 percent versus a 7.2 percent benchmark return

- Foreign equities (in developed economies) had a negative return of (1.8 percent), versus the even greater loss for the benchmark: (3.8 percent).

- And emerging-market equities yielded a loss (2.2 percent) for HMC, better than the market aggregate loss: (5.1 percent).

For HMC’s public equities as a whole, the performance in excess of market returns was a welcome recovery from fiscal 2014.

Private equities. Private-equity and venture-capital investments (about one-sixth of the portfolio) yielded an 11.8 percent return; Blyth’s letter points to robust performance of venture-capital assets, up 29.6 percent. This is in line with results reported by some other institutional investors, and the aggregate private-equity performance is better than the market return. Still, Harvard has not consistently achieved the levels of return it expected from private-equity investment, a point of concern Mendillo highlighted in recent years. The fiscal 2014 reporting format, in several segments, is not repeated this year, so it is not possible to compare performance within subcategories of private-equity investments.

Absolute return. These assets (accounting for about one-sixth of endowment investments) “had a tough year” in the language of Blyth’s letter, with only nominal returns and substantial underperformance relative to the market benchmark. He pointed in particular to losses on shipping investments, a subject of recent reporting by Bloomberg and other media. Absolute-return assets, invested by external hedge-fund managers, are explicitly designed to operate separately from the equity portfolios, and thus do not include typical long/short stock strategies. Instead, they include a mixture of investments ranging from high-yield bonds to distressed securities, assets shed by banks that are deleveraging, and so on: meaningful diversification for HMC’s portfolio, but a disappointment this year.

Real assets. HMC maintains about a quarter of its assets in this category, including natural resources (primarily timber and agricultural land) and real estate. The decision to exit investments in major categories of commodities was a blessing, Blyth reported, as the major indexes declined sharply given the collapsing price for oil, natural gas, and metals.

The natural-resources assets, now reported separately, had a positive return for the year, driven by good results in some agriculture and timber assets that were offset by weakness in certain Latin American land holdings, among other investments.

Real estate, an improving category for HMC since it began direct investing, begun in 2010; the return was 19.4 percent this year—the best asset class, and the highest margin of outperformance relative to the market benchmark. The direct investments returned 35.5 percent.

Fixed income. Although HMC does not emphasize bond investments—and has progressively reduced such holdings to about 10 percent of assets, while increasing growth-oriented equities of various sorts—its internally managed portfolios often perform strongly. The 2.1 percent return, in a year of very low interest rates, and margin of outperformance were bright spots for fiscal 2015. Blyth highlighted the international fixed-income team for achieving performance more than 12 percentage points above global market returns. In fiscal 2014, HMC’s fixed-income returns overall were 7.7 percent (some 3.5 percentage points above the market benchmark). Domestic, foreign, and inflation-indexed bond returns were all positive, with domestic assets earning 6.9 percentage points more than the benchmark, and foreign bonds outperforming by 10.0 percentage points.

A New Order

Most of Blyth’s letter (which merits reading in full) is given over to detailed descriptions of new approaches to conducting HMC’s work. Significant highlights include:

New investment goals. HMC has now articulated as its mission statement, “To help ensure that Harvard University has the financial resources to confidently maintain and expand its preeminence in teaching, learning and research for future generations.”

To realize that mission, its investment objectives are:

- “to achieve a real return of 5 percent or more, with inflation measured by the Higher Education Price Index (HEPI), on a rolling ten-year annualized basis.”

- “to achieve aggregate outperformance of 1 percent or more over appropriate market and industry benchmarks, on a rolling five-year annualized basis.”

- “to achieve performance that is in the top quartile relative to a peer group consisting of the next ten largest university endowments, on a rolling five-year annualized basis.”

On the evidence, none of these will be easy. Given a 10-year HEPI of 2.7 percent, this implies realizing returns of 7.7 percent—above the 7.4 percent goal articulated in the fiscal 2014 policy portfolio. But as Blyth points out, “real returns have declined steadily over time,” given low interest rates, greater investor interest in diverse asset classes (lowering returns as more money flows in), and so on. Accordingly, he continues, “Delivering a real return of 5 percent will be more challenging in the current environment than in the past.”

As for relative outperformance, using data extending back to fiscal 2000 (and on a rolling five-year basis, therefore extending back into the prior decade), HMC’s outperformance relative to its market benchmarks has deteriorated: from approximately 4 percent to 5 percent per year from fiscal 2000 through fiscal 2008, to a slimmer margin in the succeeding three years, and to underperformance in fiscal 2012 and 2013. For the two most recent years, the margin of relative outperformance is less than 1.5 percent.

Finally, although a 10-university sample is small, measuring from fiscal 2000 forward, HMC’s rolling five-year relative performance put it in the second quartile for four years; in the first quartile from fiscal 2004 through 2008; in the third quartile in fiscal 2009 and 2010; and in the last quartile from fiscal 2001 through 2014.

Liquidity. HMC will maintain its investments so that at least 5 percent of the endowment—equivalent to a year of operating distributions for the University budget—can be made liquid within 30 days.

Asset allocation. Blyth is a quantitative investor, and he outlines in detail a new, analytical approach to allocating HMC assets. He reports that “all asset allocation approaches are imperfect in their own way.” That said, HMC has adopted a modified asset-allocation system that is deliberately more flexible and inter-sectoral than the traditional “policy portfolio,” which is now a thing of the past. The new approach gives broad ranges for investment commitments among the many asset classes; for example, compared to the past goal of 11 percent allocations each to U.S. equities, foreign equities, and emerging-market equities, the 2016 ranges are, respectively, 6 percent to 16 percent; 6 percent to 11 percent; and 4 percent to 17 percent.

Investment processes. Blyth outlines an approach that is better suited to collaborative, cross-asset-class investments, to take advantage of HMC’s aggregate knowledge. “For instance,” he writes, “the real estate market for laboratory space for life science companies is highly related to the biotech sector within venture capital, the willingness of public equity investors to fund mid- to late-stage companies as well as the development of the underlying science. We will develop a strong culture of constructive challenge and comparison of investment opportunities across the portfolio.” He is also trying to encourage new kinds of partnerships and vehicles for investing, and the willingness to commit to good ideas on a large scale, given the size of the endowment.

Compensation. Blyth is working on a new compensation system tied not only to each portfolio’s outperformance relative to its asset class and benchmarks, but also to HMC’s performance as a whole, on Harvard’s behalf, in keeping with the mission statement.

Outlook. Blyth cautions about increased market volatility during the past year, after an extended period of calmer conditions; about changes in regulation affecting banks and other financial institutions; the impact of “the eventual rise of interest rates” in the United States (very much on the mind of investors in recent weeks); and about current valuations. On the latter point, he notes:

[P]rivate equity valuations are now, on average, at higher levels than in 2007. There are over eighty “unicorns” (venture-capital portfolio companies with valuations over $1 billion), as many as in the last three years combined. Venture capital continues to receive ample funding, and private company valuations are also bolstered by public mutual funds entering late stage funding rounds in significant size. This environment is likely to result in lower future returns than in the recent past.

More generally:

We are proceeding with caution in several areas of the portfolio: many of our absolute return managers are accumulating increasing amounts of cash; we are being careful about not over-committing into illiquid investments in potentially frothy markets, while still ensuring we will be involved if market dislocations arise; and we are being particularly discriminating about underwriting and return assumptions given current valuations. In addition, we have renewed focus on identifying public equity managers with demonstrable investment expertise on both the long and short sides of the market. And we are concentrating on investment opportunities with idiosyncratic features that still offer value creation, such as the life science laboratory space, and the retail sector where transformation continues at rapid pace.

And on a personal note:

I know that my colleagues at HMC share deeply the special role that HMC plays in the support of our great University.

We have clearly stated this mission and have laid out straightforward, ambitious investment objectives. I have found my first nine months as CEO to be intensely fulfilling and intensely enjoyable. I will do everything in my power to maximize the probability of HMC achieving its objectives over the coming years and decades. We have challenges ahead and much hard work to be done, but I believe we have gained significant traction in 2015, and I am highly optimistic that we can achieve our goals.

Read the HMC annual letter and a University news release here.