On June 10, two days before its fortieth-anniversary celebration, Harvard Management Company (HMC)—which invests the University endowment and other assets—announced that Jane L. Mendillo, president and chief executive officer since July 2008, would depart at the end of this year. Her plan to step down surprised close observers. But the long lead time before her departure—making a regular search for a successor feasible—and general confidence in the organization and strategies suggest that the transition will proceed in an orderly way.

In an interview with Andrew Bary of Barron’s in February, Mendillo called running HMC “the best job in the world” and said, “I’d like to be here for as long as I’m adding value.” Paul J. Finnegan ’75, M.B.A. ’82—an HMC board member since March, whose selection as the University’s new treasurer was announced on May 28—said in conversation the day after Mendillo’s departure was reported that he was surprised. Discussing her tenure, he hastened to add that she had “joined at a less than ideal time” in world financial markets, and put in place changes in HMC and its controls and processes that made it “seem well positioned for future positive performance.” Mendillo herself, he said, felt the organization was “humming,” enabling her to “step back” without causing disruption.

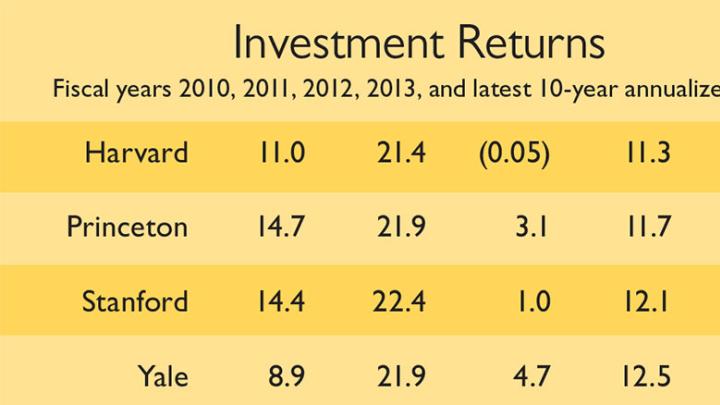

Mendillo became HMC’s leader just months before the financial crisis erupted, devastating the markets and threatening the University’s liquidity: during the fiscal year ended June 30, 2009, investment returns were a negative 27.3 percent, and the value of the endowment plunged nearly $11 billion. It fell to Mendillo and colleagues to manage cash, steer through contracted commitments to invest funds with outside managers in future years, and build a new system for managing investment risk to meet the University’s cash needs. Returns were stronger as the markets recovered (11 percent in fiscal 2010; 21.4 percent in fiscal 2011) but still volatile (returns were a negative 0.05 percent in fiscal 2012 before recovering to 11.3 percent last year). The University’s financial leaders—the treasurer and chief financial officer—have made a point of projecting more subdued endowment investment gains in the future, compared to the mid- to high-teens long-term rates of return enjoyed for decades before the 2008 meltdown. President Drew Faust made such concerns a central theme of her academic-year opening remarks last September (see harvardmag.com/future-14).

Mendillo championed investing in certain real assets, such as timberland, and had enormous, early success in that area. (From 1987 to 2002, she was a senior investment officer at HMC, rising to become vice president of external investments and overseeing a portfolio that grew to $7 billion; she then directed Wellesley’s investments before returning to Harvard.)

Of late, slower growth in the developing world, particularly China, has put pressure on several kinds of real assets and commodities; Harvard’s holdings underperformed their benchmark during fiscal 2013. HMC has also been challenged by less than stellar results in private equity, long a strong category for the fund managers, and now targeted for some 16 percent of the endowment’s model policy portfolio. Because such assets are less liquid than public securities, investors expect greater returns for the risk they assume, but Mendillo’s fiscal 2013 report on HMC stated that recent private-equity performance was “fair” and that for the past decade, “our private-equity and public-equity portfolios have delivered similar returns.”

In the past few years, Harvard’s performance has trailed that of peer institutions with the largest endowments and roughly similar investment strategies: highly diversified assets, and a robust appetite for less liquid assets that promise greater long-term returns. (The strategies, actual investments, and universities’ financial aims and needs of course differ. HMC no longer reports its performance relative to the Trust Universe Comparison Service, a common industry metric for large endowments.)

The differences in rates of return may not seem huge, but a percentage point on Harvard’s endowment ($32.7 billion as of June 30, 2013) is nearly one-third of a billion dollars: a large sum, particularly if compounded over time. (The 10-year annualized return captures Harvard’s especially severe losses in fiscal 2009.)

In mid July, Bloomberg reported that HMC’s employee compensation is higher than that of other university endowments, but investment returns during the past five years are lower (“Harvard Leads in Endowment Manager Pay as Returns Trail Peers”). HMC’s pay packages, disclosed annually, are a perennial public-relations issue; other schools invest wholly with external money managers, many of whom no doubt earn much more than HMC staff members (as some of Harvard’s external managers likely do, too)—but those figures are private. The larger issue is the rate of return. HMC maintains that by managing 40 percent or so of assets in-house, it effects large expense savings. But even with those economies, which are included in the rate-of-return numbers, HMC’s net performance lags behind peers’ results.

As possessor of the largest endowment, Harvard may face the toughest performance challenge. Changes in its strategy may also enter into recent results. When asked if HMC’s decisions—to adopt a more conservative posture meant to make the portfolio more liquid; to forgo leverage (borrowing) to boost returns—had penalized returns lately, Mendillo said such decisions were less consequential than “market-wide factors” in shaping current and prospective returns. Given low interest rates and a more subdued outlook for public- and private-equity gains compared to prior decades, she called it reasonable to expect lower market returns overall. And, she emphasized, “our alignment of the endowment with University needs for liquidity is improved” (a factor that might override any minor cost in terms of lower returns). Today, she said, “We know we can deliver what the University needs” and won’t have to scramble to sell or redeploy assets, or take other emergency steps, in a future down market (the threat that forced Harvard to borrow $2.5 billion in late 2008). “We feel good about that.”

Finnegan—co-chief executive officer of Madison Dearborn Partners, a private-equity firm—noted that recent performance may be penalized by “legacy” issues from prior long-term investments, and may not indicate the expected results from newer investments. Indeed, Mendillo maintained that HMC has good “alpha generation opportunities” (the professional term for generating returns in excess of the market). She cited changes in regulation affecting other investors (such as commercial banks’ allowed investments and required capital cushions) that create new opportunities for Harvard—plus the continuing strengths of the in-house real-assets and natural-resources asset managers, the new direct real-estate investments, and HMC’s long-term fixed-income trading expertise.

Olshan professor of economics John Y. Campbell looked beyond particular investments or even asset classes to put HMC’s outlook in a broader context. The largest endowments, including those at Harvard and Yale, were “early to adopt” the current model of highly diversified investments defined by a policy portfolio, use of illiquid assets, leverage, and so on. As first movers, they secured advantages, and returns to match, that have now attracted other investors. “The competition has wised up,” said Campbell, a scholar of asset management, finance, and investing, and an HMC board member from 2004 to 2011. The top-performing endowment in any given year is now “more a matter of luck,” he added; it would be unwise to expect Yale and Harvard always to lead the rankings.

He also noted that the most successful external money-management firms (in private equity, for example) typically give big customers equal dollar allocations when raising new pools of funds to invest. For a larger endowment like Harvard, that translates into a smaller percentage of its assets, making it harder to achieve superior returns overall, even if the investment performs well. (Campbell knows about such matters: he is a founding partner of Arrowstreet Capital LP, a Boston-based quantitative asset-management firm with $50 billion under management at last report.) Finally, he noted that Harvard’s prowess in fixed-income arbitrage (a long-term source of superior performance for HMC) is somewhat blunted by today’s very low interest rates, which limit absolute returns.

In light of such structural constraints, Campbell concluded, as an outsider, that HMC “is doing reasonably well.” He also pointed to the much-enhanced coordination of HMC risk management and University financial planning, and the strengthening of both, as “one of the very important things about Jane’s legacy.”

The search committee has an interesting task. Harvard’s assets are much more complex than those of, say, a comparably sized fund consisting only of stocks or bonds. HMC’s results are published and widely scrutinized, as is the compensation of its CEO and top fund managers: visibility that investment professionals at private firms can avoid. The investments themselves are subject to heightened scrutiny for environmental and social impacts—witness the continuing advocacy by some students and faculty members for divestment of fossil-energy assets. The CEO reports to a board of experts in private equity, public securities, and other parts of the financial markets—a strength, one assumes, but perhaps challenging supervisors. The expanded Harvard Corporation itself now includes private-equity, venture-capital, and other investment experts. And The Harvard Campaign is drawing large gifts from the same community, and offering supporters who make substantial endowment gifts the long-term record—and presumably the hope of future strong investment returns. After six years, at age 55, Mendillo has chosen to step down from “the best job in the world,” to take time to pursue personal and other interests—and pass the torch to someone eager to grapple with Harvard’s emerging investment challenges.