A certified Boston Brahmin, Alexander Hamilton Rice, A.B. 1898, M.D. 1904, was a true Harvard man who served as a faculty member and director and founder of the Harvard Institute of Geographical Exploration (1929-1952). His ultimate passion, though, was green rather than crimson: he traversed and mapped enormous tracts of Amazonian rainforest in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Thus perhaps the most consequential moment of his Harvard career was Commencement day in 1915, when the “explorer of tropical America, who heard the wild call of nature and revealed her hiding-place” received an honorary degree and met Titanic survivor Eleanor Elkins Widener, present for the dedication of the library named for her drowned son. Rice and Widener married later that year and soon set out together for South America; her vast fortune expanded the scope and scale of his fieldwork and supercharged his career.

The Roxbury-born Rice developed wanderlust early, traveling from Istanbul to the Caucasus before finishing college, then finding time to visit Greece, Russia, France, and the Austro-Hungarian empire, play polo in Egypt, and ride to hounds in England before finishing his medical degree. But the trek following his first year of medical school truly set the stage for his greatest adventures and accomplishments. In June 1899, he headed to Winnipeg and then set out for Hudson Bay, traveling as a traditional French-Canadian voyageur. He paddled and portaged his canoe through the wilderness, journeying overland and studying the terrain, the people, the flora and the fauna; all told, his extraordinary expedition covered more than 1, 400 miles. The experience inspired a quarter-century of exploration of the most remote and least known corner of the Western Hemisphere: the northwest Amazon—terra incognita that Rice did much to transform into terra cognita.

His first visit, in the summer of 1901, retraced the 1541 voyage of conquistador Francisco Orellana, the first European to travel from Amazonian headwaters to the Atlantic. Rice traveled from highland Ecuador, over the snowcapped Andes, down through the montane forests of the eastern slope, and into the rainforests below to reach the great river. Despite the man-eating black caimans, vampire bats, riverine stingrays, giant piranhas, electric eels, ubiquitous sandflies, flesh-eating botfly larvae, burrowing toe fleas, tarantula hawk wasps, goliath bird-eating spiders, and tocandeira bullet ants, he fell in love with the Amazon and embarked on a quest to find the sources of rivers that were little more than vague scribbles on maps. So successful was he, it was often said he knew headwaters the way other men of his social class knew headwaiters.

For professional cartographic training, Rice enrolled in a program at the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) in London; he used what he learned there to produce fine maps of some areas so forbidding and remote that few nonindigenous people venture there even today, more than a century after his expeditions.

In all, Rice led seven Amazonian expeditions: his first consisted of himself and some local guides; one of the last included more than 100 men. Along the way, he conducted research on tropical diseases, carried out the first surgical operation under general anesthesia in the Amazon, taught the fundamentals of South American exploration to Hiram Bingham, Ph.D. 1905 (who stumbled across Machu Picchu); made the first detailed map of Chiribiquete, the most spectacular landscape in Amazonia (now Colombia’s largest national park); and pioneered the use of aerial photography and shortwave radio to map the rainforest more accurately and efficiently.

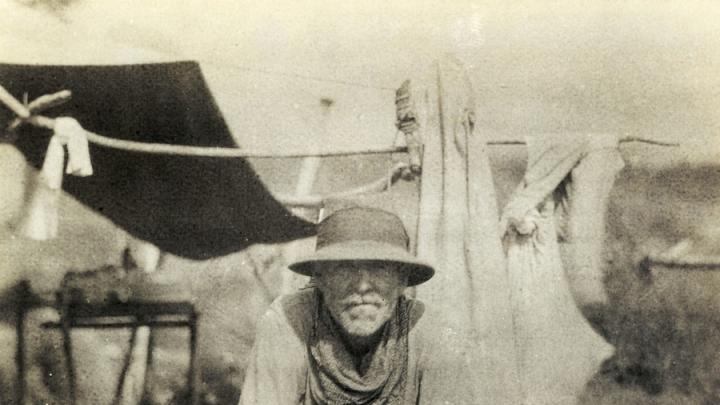

By turns elegant socialite and swashbuckling adventurer, Rice relished press coverage—his departures to and returns from the Amazon were breathlessly reported in The New York Times—and he proved an almost endless source of good copy. “Explorer Rice Denies That He Was Eaten By Cannibals” is a hard headline to top. He also attracted ample criticism. A pugnacious former boxer who was chauffeured around in a blue Rolls Royce and lived in a 65-room Newport mansion during the depths of the Depression risked at least some resentment in Cambridge, but he has been accused of using his wife’s money to “buy” his academic position and his many awards, of lacking academic credentials and employing outdated cartographic techniques, and of shirking teaching assignments to spend more time in Europe. His conduct has been blamed for destroying the academic study of geography at Harvard.

In rebuttal, former RGS director John Hemming, the leading authority on the history and mapping of the Amazon, notes that Rice received his most prestigious awards—the Harvard honorary and RGS Patron’s Medal—before his marriage. Rice’s work in Amazonia has also continued to benefit conservation: for example, it attracted ethnobotanist Richard Schultes ’37, Ph.D. ’41, who revealed Chiribiquete’s botanical treasures and led the effort to have the area declared a national park. (The Colombian government is now planning to double its size.) And throughout the world, conservationists who map, manage, and protect vulnerable ecosystems by utilizing aerial photography and satellite imagery to mark boundaries and monitor incursions are following in the trailblazing footsteps of Rice and his colleagues who—in the words of a plaque at 2 Divinity Avenue, the building that once housed Rice’s institute—“laid the foundations for the mapping of the world from the air.”