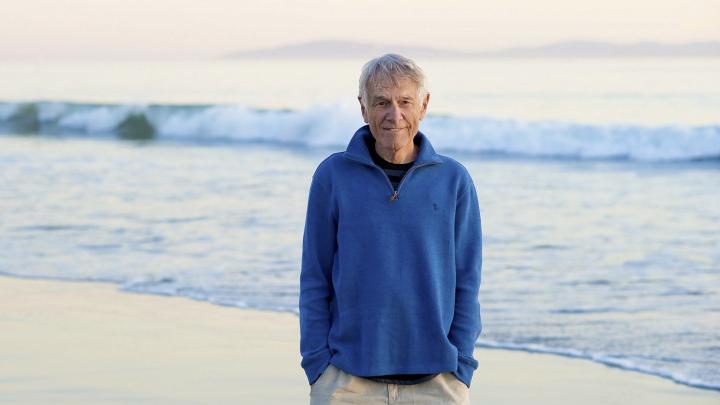

In 1970, his bestselling book, The Pursuit of Loneliness, made Philip Slater ’50, Ph.D. ’55, a famous author whose photo appeared in Time magazine. Subtitled “American Culture at the Breaking Point,” the book developed a searing critique of American culture, describing many of its ills—violence, inequality, and worship of technology among them—as fallout of the national cult of individualism that fostered isolation, competition, and loss of community. The book made Slater an intellectual hero of the counterculture, then at its high-water mark.

One year later, at age 44, he disproved F. Scott Fitzgerald’s claim that “there are no second acts in American lives.” Slater had been a professor of sociology at Brandeis since 1961 and eventually chaired the department. But “the university disappointed me,” he recalls. Academia wasn’t the fount of brilliant ideas he had imagined, though he did enjoy his time there. He felt that “as a teacher, I wasn’t that good at conveying content in lectures. I thought I could maintain myself by my writing, so I left. That was a mistaken assumption: it’s been hard going financially.”

Not that Slater the author (www.philipslater.com) hasn’t been prolific. His 12 books include The Glory of Hera: Greek Mythology and the Greek Family (1968), Earthwalk (1974), Wealth Addiction (1980), A Dream Deferred: America’s Discontent and the Search for a New Democratic Ideal (1991), and a novel, How I Saved the World (1985). His latest book, The Chrysalis Effect: The Metamorphosis of Global Culture (see sidebar, “The World According to Slater”), may be his most ambitious. He’s also written 20 plays and acted in 30 in Santa Cruz, California, where he has lived for the past four decades, currently near a bird sanctuary on Tree Frog Lane.

“What I’m proudest of in my life,” he says, “is that I have four bright, interesting, creative, and fun children who love each other and enjoy hanging out together.” (Wendy, Scott, Stephanie, and Dashka, three from his first marriage and one from his third, now range in age from 49 to 64.) His fourth and current spouse is photographer Susan Helgeson. “It’s been a very satisfying life, in nearly every way,” he says.

Slater probably set out on the path to sociology and social criticism by growing up the son of a frustrated scholar. His father, John Elliot Slater, A.B. 1913, was president of a shipping company and chair of the New Haven Railroad, but “had an unfulfilled desire to be an academic,” Slater recalls. “One reason I left the university is that I realized I was playing out his road not taken.”

He attended public schools in Montclair, New Jersey, declining private school because “there were no girls there.” After high school, with World War II still raging, he spent two years in the Merchant Marine and “foolishly married my high-school sweetheart,” he says. Hence, his “extracurricular activities” at Harvard were being a husband and parent; he concentrated in government.

“My whole academic career was guided by choosing the path of least specialization,” he says. “I did not like looking at the world through one lens—it seemed too limiting.” In 1952, during graduate work in the field of social relations, he became one of the first people in North America to take LSD, years before Timothy Leary heard of psychedelics. This happened at Boston Psychopathic Hospital under the auspices of Harvard Medical School psychiatrist Robert W. Hyde, who became Slater’s mentor: “a brilliant man, who had a kind of unfettered mind.” Slater adds that, “if you take LSD and take it seriously, you never look at the world the same way again.”

He taught at Harvard for six years as a lecturer and leader in the group-process course, Social Relations 120, before joining the Brandeis sociology faculty in 1961. “The department was very cohesive, very radical—in teaching methods, and so on,” he recalls. “So we were hated by the rest of the university. It was one battle after another—constant harassment.” He recalls an assistant professor who remarked, in a course on gender, that “every man should know how to cook a meal.” The rumor soon circulated that the final exam in the course was cooking a meal.

The success of Pursuit of Loneliness led to some lucrative book advances, which convinced Slater he might support himself by writing. After leaving Brandeis, he joined with Jacqueline Doyle of the Esalen Institute and former Brandeis colleague Morrie Schwartz (of Tuesdays with Morrie fame) to found Greenhouse, a personal growth center in Cambridge: “I was running all kinds of groups, [humanistic psychology pioneer] Carl Rogers was there, it was a very exciting time.”

A serious romantic relationship drew him to Santa Cruz in 1975. The next fall, Slater’s female companion returned to Cambridge to take a job, and “I found myself feeling abandoned,” he recalls. Simultaneously, a publisher canceled a book contract with a $30,000 advance payment remaining, and even sued the author to recoup the original $30,000 installment. “I was here in a strange place with no job, no income, no girlfriend,” he recalls. “It was one of the happiest times of my life.” He joined a men’s group that he continues to attend, 35 years later, and began stage acting, which he had never done.

Today Slater remains in Santa Cruz, where he walks on the beach every morning, explaining, “I am addicted to the ocean.” Since 2007 he has taught at the San Francisco-based California Institute for Integral Studies, where he offers a required course for graduate students, “Self, Society, and Transformation.” It’s an online curriculum that also includes an intensive five-day residential session each semester—“very, very multidisciplinary, which is why I like it,” he says. “What I love is that the students are all adults, mostly in their forties and fifties. They are very interesting people—open-minded, excited, motivated—who decided to get a Ph.D. They come from all over the world.”

Most of the students know and admire Slater’s books, as well. “The thing about being famous,” he muses, “is that it’s sort of sickening how some people respond to you. They’ll say, ‘Your book changed my life,’ but then it becomes clear that they haven’t read the book and don’t have a clue what is in it. I’ve had people treat me as ‘someone famous’ and try to get on board in the crudest ways. Once, a woman said, ‘I haven’t read your book [The Pursuit of Loneliness] but I’ve been looking at you in this discussion and you look lonely.’ ” A pause. “Fortunately,” he adds, “I’ve drifted into obscurity.”